Targets are great motivational tools—to both deceive as well as achieve. In China, the government’s promotion system sees local officials overstate their provincial outputs to the tune of a few trillion yuan, for example. It’s not just Communist Party cadres with a knack for embellishment, though. Bloomberg just busted Wal-Mart China for rampant accounting and inventory shenanigans dating back to 2009.

And now it’s BMW’s turn. Dealerships across China have united to demand that the German luxury carmaker relax corporate policies that have forced them to absorb inventory and swallow losses, as consumer demand for BMWs has slowed.

Part of the tension comes from BMW’s outsize clout vis-a-vis dealers; but another element arises from the Munich headquarters’ reward system and its setting of unrealistic expectations that encourage dealers to make unprofitable sales. Yes, BMW’s numbers look impressive, but they obscure reality. Worse, they perpetuate expectations that are even more unrealistic.

BMW shines in China

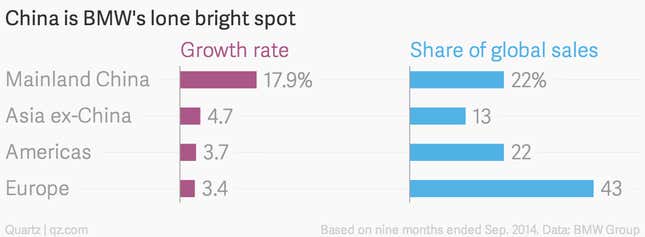

BMW’s China sales have been outstanding this year. Growth in its wholesale volumes—i.e. sales from BMW to its licensed mainland China dealerships—surged nearly 18% in the first nine months of 2014, compared with the same period in 2013.

And though its China sales dipped a bit in the third quarter, October heralded a recovery:

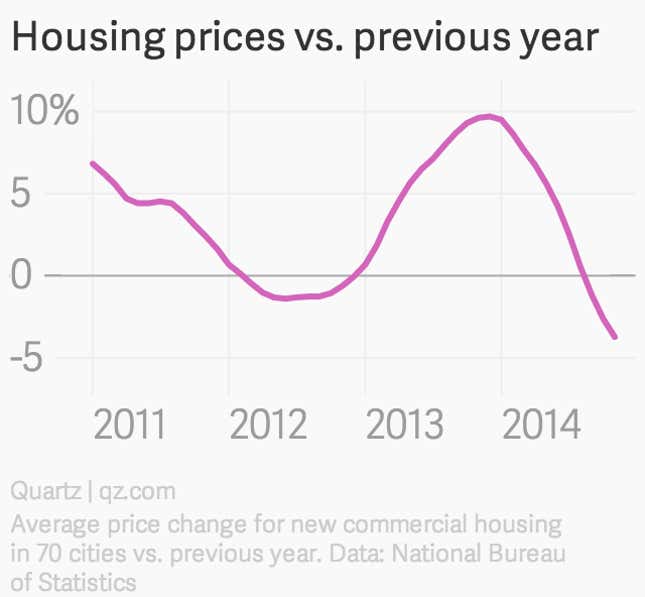

What’s strange is that, all across China, car sales have been slowing. The 1.8 million passenger cars (for all brands, not just BMW) sold in November marked a mere 4.7% increase versus November 2013—the lowest growth since September 2012:

BMW’s conspicuously rosy wholesale numbers don’t necessarily reflect what’s happening at its China dealerships.

BMW grants Chinese dealerships licenses to sell its cars exclusively. The dealerships themselves shoulder the expense of renting and swanking up the sprawling, opulent showrooms—some of them with chi-chi cafeterias—that welcome potential customers. Building a single dealership requires an upfront investment of at least 100 million yuan ($16.1 million), one dealer told China Real Time.

The dealerships buy the cars upfront and are promised certain incentives—notably a cash subsidy called a “rebate” and more financial support if they hit certain sales volume targets. A BMW executive told the Wall Street Journal (paywall) that it awards dealers with a 5-6% rebate for each new car they sell. But missing targets means missing out the performance-based incentives, and could put dealerships at risk of losing their license to sell BMWs the next year.

Dealers sell their BMWs for more than they paid wholesale, and pocket the difference. But the pricing doesn’t offer much wiggle room. More often, nearly all of their gross margin comes from the rebates that BMW pays them for the cars they sell and if they hit their sales targets.

Great expectations

Generally speaking, this manufacturer-dealership setup is how it works in most markets, and for most car brands. Where China differs from everywhere else, though, is in the expectations it inspires. Not only is the country amidst a 36-year growth streak of no recorded precedent; urban wages are rising by nearly a tenth each year, buoying a middle class that’s now surpassed 200 million, about the size of Brazil. Companies like BMW are told to expect this unique market to continue powering their growth for a decade or even more.

These expectations have been met—until recently, that is.

Junheng Li, head of JL Warren Capital, recounts a recent conversation with a senior manager at a BMW 5S model store in Beijing who explained that in 2013, his BMW dealerships earned 27 million yuan in profit after selling 600 Series 518 cars. Almost all of that came from the rebate awarded for hitting his targets.

So far this year, however, the manager has seen his dealerships suffer a loss of 34.4 million yuan on sales of 800 cars—largely because he sold the cars for less than the wholesale price he paid for them in the first place, says Li. Though it might seem strange that the Beijing dealer sold a third more cars this year even when he was unloading them at a loss, it’s nonetheless common.

“Many dealers are buying many more cars than consumers want,” Li Jinyong, president of China’s third-largest auto dealer by revenue, told the Wall Street Journal (paywall).

Since dealers get most of the rebate when they hit sales targets, dealers are pressured to keep buying cars from the wholesaler, even when they know they can’t sell them profitably. This is commonly called xubao (link in Chinese), meaning “false reporting,” since it lets BMW report impressive numbers, underwritten by cash-desperate dealers.

This cycle self-perpetuates. Dealers buy a bunch of inventory that they know they can’t sell and end up slashing prices to move cars out of their showrooms. News reports since the summer have noted discounting of 25% to 35%. Sometimes BMW’s regional distribution managers take the opportunity to slough off unpopular, little-promoted models, prompting additional discounting and pinching dealers even more.

Behind the slowdown

There’s some disagreement as to why BMW’s sales are in such disarray. While many point to president Xi Jinping’s so-called anti-corruption crusade hurting the luxury market, the fact that car sales across all price ranges have fallen of late makes that seem unlikely. The problem is widespread enough that Yicai Financial, a Chinese newspaper, reports that more than 60% (link in Chinese) of BMW and other dealerships are now running at a loss. Scores of others have folded.

Norbert Reithofer, BMW’s CEO, blames regulatory tightening as the government reins in new car registrations to combat air pollution. Others cite market saturation as China’s incipient used-car market begins developing and as city streets have become overwhelmed by traffic.

“After real estate, what’s next? Auto. Why? It’s a big-ticket expense,” says Li. “And BMW buyers were the fast money—the guys [making money in] infrastructure and resources—coal, steel, iron ore.”

It was those very customers who benefited handsomely from the Chinese government’s response to the global financial crisis in late 2008—namely, a 4 trillion yuan stimulus that juiced infrastructure and industrial spending, boosted all the more by directives to state-owned banks to lend like crazy.

During those years, BMW dealerships sprouted up across China. Starting in late 2010, luxury dealerships clamored to list on the Hong Kong stock exchange, all told raising billions in capital to spiff up their showrooms and expand their reach.

The end of easy money

That “fast resources and infrastructure money,” says Li, has since vanished. As the central bank has gradually reined in lending, coal mines and steel smelters have been going belly-up, their bosses fleeing the country. The housing market has shriveled, followed by the collapse of Macau casino revenue. Though the economy in general has been grinding slower, the lack of remotely real reporting on bad loans suggests that growth is much more sluggish than it appears.

The united front of dealers that issued the litany of demands (link in Chinese) in late November asked that BMW offer 6 billion yuan in compensation for dealers’ 2014 losses and negotiate sales targets with their dealerships instead of handing them down by fiat. They also told the carmaker that it “shouldn’t be allowed to ask dealers, whether explicitly or implicitly, to xubao.” (At the time of publishing, BMW had not responded to Quartz’s request for comment.)

In short, to bring sales and price expectations more in line with reality. At their headquarters in Munich, BMW execs are still mulling how to respond. However much the company ends up revising down its hopes for China’s growth potential, you can be pretty sure BMW won’t be the last company adapting to the new reality in China.