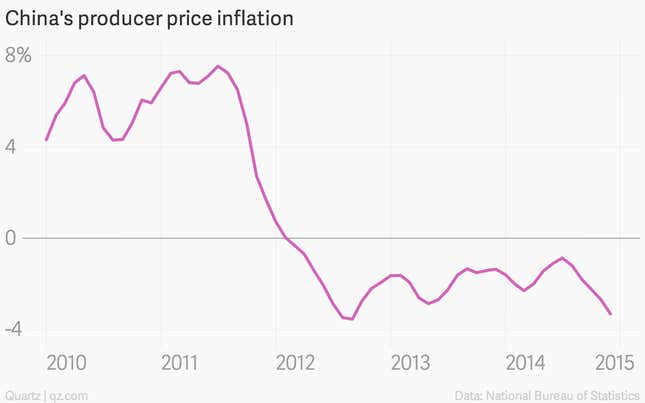

Last year wasn’t an easy one for China’s economy. And though we’re only a few days in, 2015 is looking even tougher. In December, the producer price index—an average of the change in prices that producers charge for their wares—fell 3.3%. Not only was that the 34th consecutive month of falling prices, it also marked a quickening pace since November, when prices fell by 2.7%.

Worried murmurs are now linking not just Europe, but China to the D-word. And Chinese deflation fears may be justified, but for somewhat different reasons than in Europe.

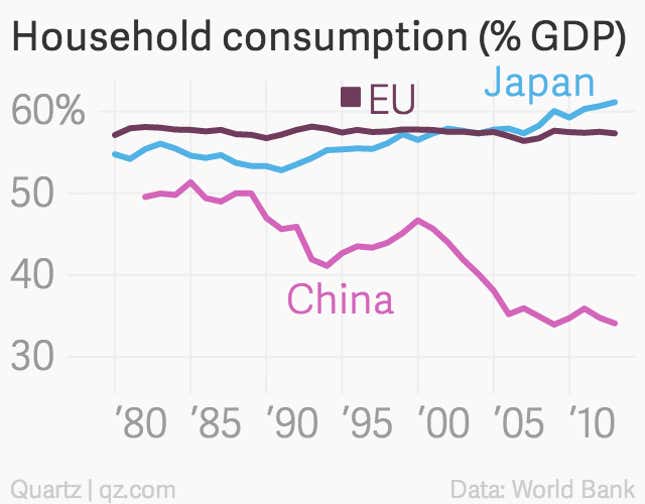

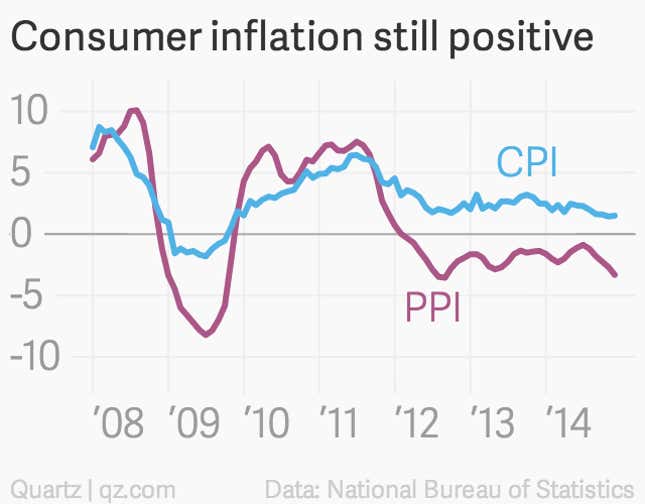

A big concern there is that deflation will suppress overall consumption, since when consumers see prices falling, they’ll postpone purchases. That’s not an immediate worry for China. December consumer prices rose 1.5%—weak but still positive. (Given how little households contribute to China’s GDP, however, this is less heartening than it might be.)

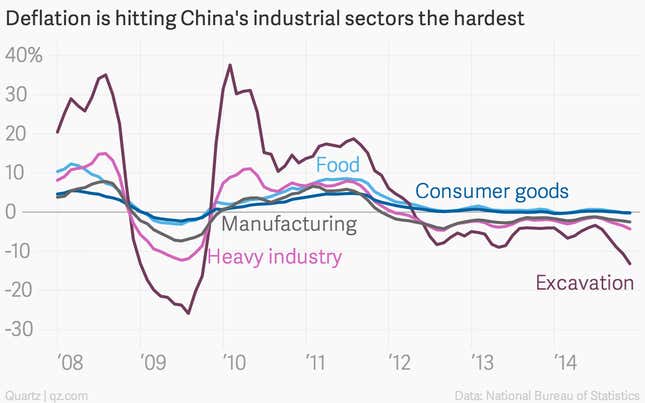

Industry drives much more of China’s GDP, and the prices picture on that front is far from pretty. Enriched by China’s ongoing lending spree, industrial companies have produced far more goods than the economy needs, causing “fierce” price competition, explains Jianguang Shen, economist at Mizuho, in a note. Iron products, for example, plunged nearly 20% in December, while coal dove 12%.

Of course, cratering global commodity prices are also dragging down PPI, notes Chen Long, an economist at GaveKal.

On the flip side, cheaper commodity imports should be good for Chinese companies, relaxing margin pressure. But that’s not usually what happens in China. Profits of its major industrial sectors rise and fall with commodity prices, says GaveKal. And industrial fortunes, in turn, are tightly tied to broader corporate profits. For instance, in the first half of 2014, China’s corporate profits looked pretty good—up 12% versus H1 2013—especially when you take the tanking property market into account. But after iron ore and oil prices fell by nearly half, and coal prices slumped 20%, that profit growth collapsed.

When companies aren’t profiting, they can’t raise wages, let alone hire. Yet workers have come to expect the double-digit increases in income that they’ve enjoyed each year for more than a decade, as GaveKal flags, making it likely households will curtail spending. Grim news for the Chinese government’s plan to “rebalance” its economy, shifting away from industry- to domestic consumption-spurred growth.

And that, in turn, would make consumer price deflation more likely—particularly given CPI is already at a five-year low—which brings us to another problem with China’s deflation flirtation. While inflation erodes borrowing costs and debt, falling prices effectively do the opposite—a big issue for a country that’s amassed at least $14 trillion in corporate debt.

This is where China’s fate starts turning Japanese. Unless its leaders loosen credit, that could set off a wave of defaults, notes David Cui, strategist at Bank of America/Merrill Lynch, in a recent note. But keeping bankrupt companies afloat with cheap money lets them keep making more goods that no one wants. As those “zombie” companies suck up bank loans and further drive down prices, they prevent viable companies—the ones that China needs to power growth—from having a chance to compete.