Imagine this: McDonalds knows you’ve been driving three hours with your tyke in the backseat and the little sprog is getting hangry. An alert on your dashboard lets you know there’s a McDonalds at the rest stop just one mile up the road. Why not take a break?

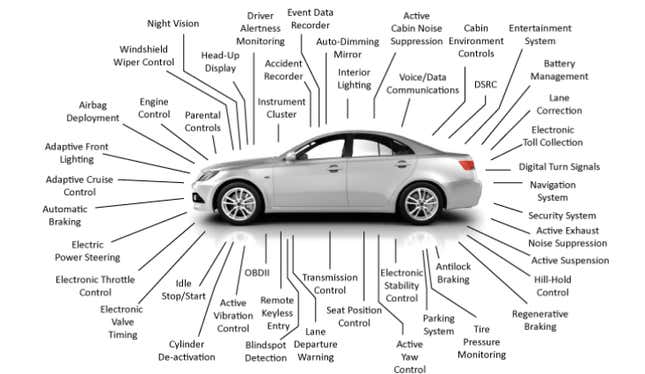

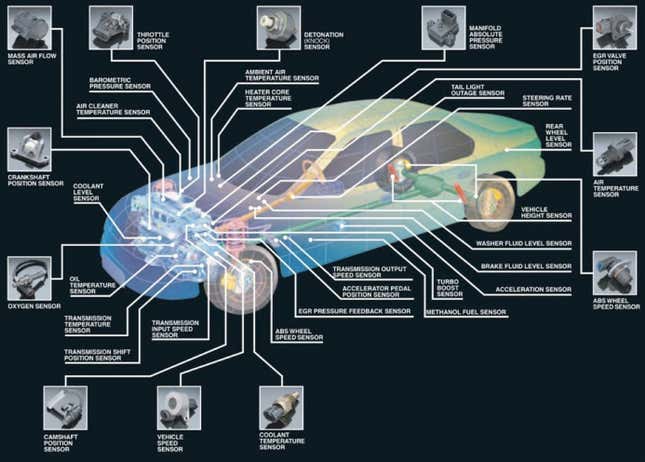

This is not today’s world. But it could very well be tomorrow’s world if advertisers have their way, BMW’s Ian Robertson tells the Financial Times (paywall). How would McDonalds know all this? Modern cars are increasingly crammed full of sensors and silicon. Indeed, the automotive sector will provide the highest rate of growth for semiconductor companies over the next decade as they increasingly integrate chips and sensors into cars, according to a research note published today by Liberum, a bank and broker.

Even with today’s technology, McDonalds could still make the prediction: Given access to data, it would know how long your engine has been running; sensors in the seats figure out whether an occupant a child by body weight; and GPS tells it where you are and whats nearby. The only thing standing between this scenario and your car today are auto companies, which are reluctant to part with their data.

“There [are] plenty of people out there saying: ‘give us all the data you’ve got and we can tell you what we can do with it’,” Robertson told the FT. “And we’re saying: ‘No thank you’.” Interest has come both from large advertising companies as well as Silicon Valley firms. (BMW responded to a request for confirmation with a note that a “relevant spokesperson” will contact us; we will update this post when they do.)

That advertisers and tech firms are looking at connected cars as another source of data for their ever-expanding empires of data and profile-building should come as no surprise to anybody who has been paying attention. But most examples of how it would work tended to relate to GPS and what a driver happens to be passing. The example offered by BMW’s Robertson is much more sophisticated—and somewhat unsettling.

Already automotive data is used—with clear, explicit opt-ins—by insurance firms that offer the carrot of lower premiums in exchange for data. But for something like advertising, the proposition is trickier, says Caroline Coates, a partner at DWF, a law firm. ”We’re used to sales becoming more personalised and targeted,” for example on Amazon, she says. But ”do you as the driver want that? You would have to consciously sign up to your data being used by others and at the moment that is not something I am aware of.”

Car manufacturers are in a tricky position. On one hand, they don’t know how on earth they’re actually going to make money from all this connectedness. A little data-sharing could result in juicy payments. But on the other hand, they have no interest in giving up their data to third parties; it would be more sensible for them to use it themselves, for example to let customers known when a service is due.