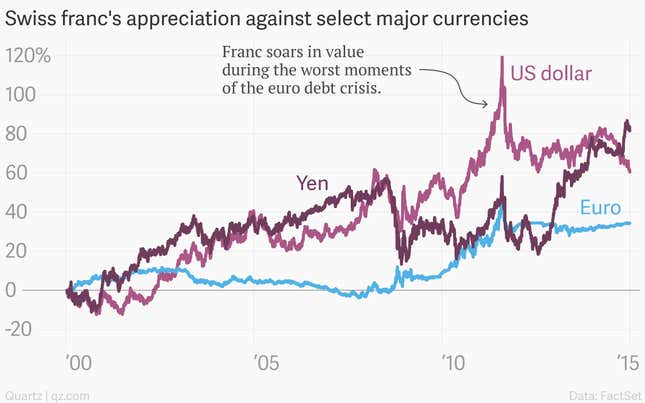

The Swiss franc is a very popular place to park cash.

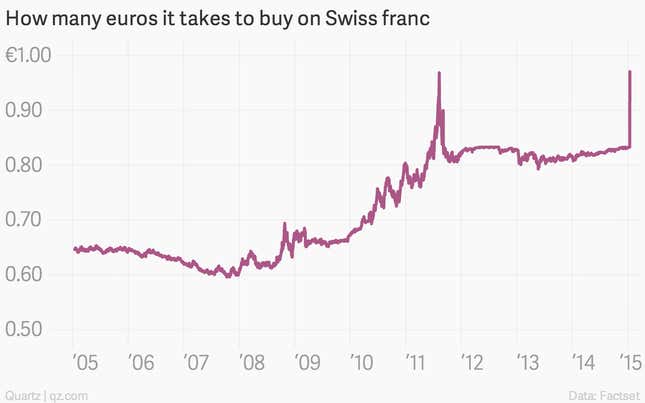

Amid the euro zone debt crisis, demand for the franc surged, pushing its value up sharply.

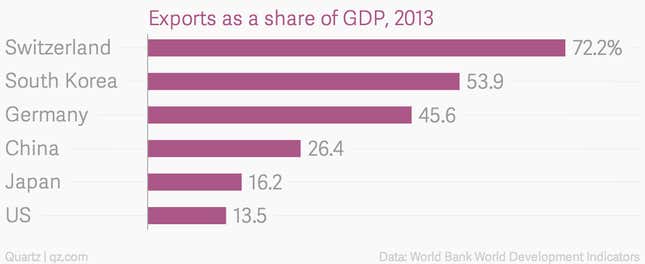

That’s bad for exports…

A strong franc hurts the Swiss because it makes their exports more expensive for foreign buyers, and the country has a giant export sector.

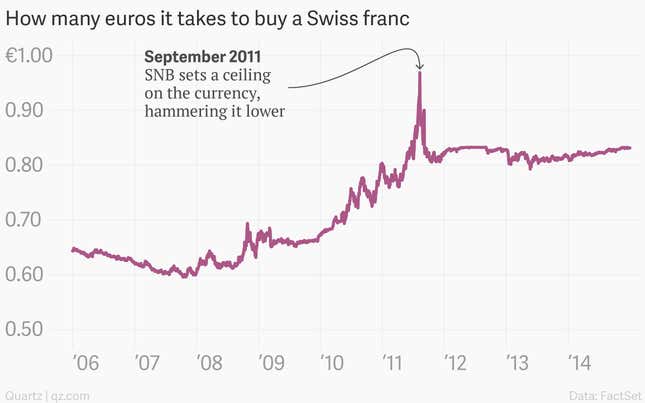

So the central bank put a ceiling on the franc’s strength.

In September 2011, the Swiss National Bank set a limit on the amount of strength it would tolerate, vowing to use its power to print money and use that freshly printed money to buy “unlimited quantities” of foreign currency. The ceiling worked, for a while.

But there was a problem.

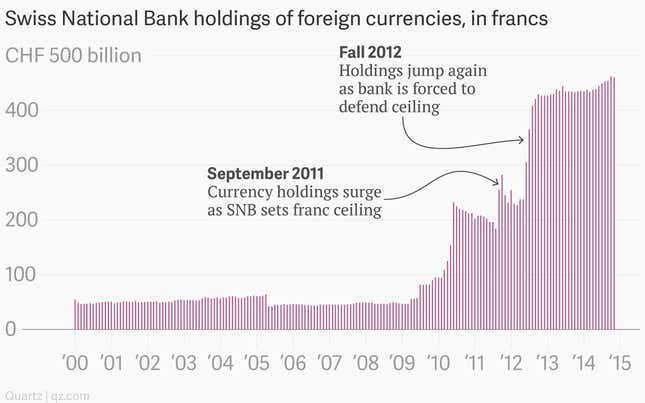

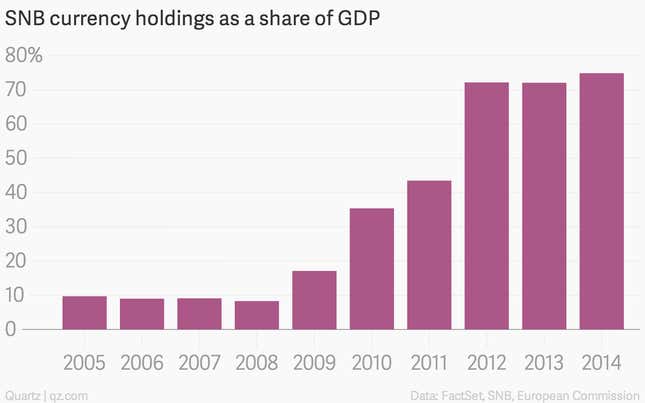

Because it was creating new francs and using them to buy euros, the SNB’s currency holdings exploded. This is hugely important. In the United States, the Fed is buying the safest financial instrument in the world, US government bonds. It can hold those bonds until they mature and be virtually assured it will be paid back. The SNB, on the other hand, is acquiring a giant pile of currencies that can whipsaw in value, potentially exposing the bank to large losses.

But isn’t that the same thing the Fed is doing?

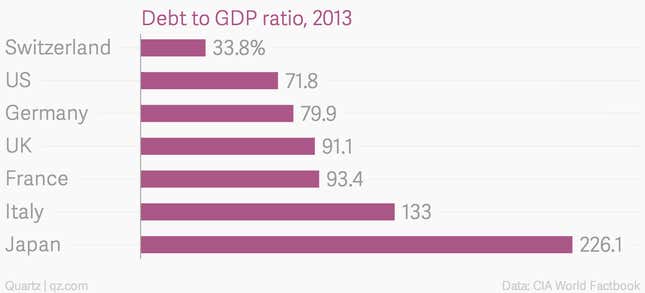

No, it’s different. The Fed is creating money and buying US government bonds. The SNB is creating money and buying foreign currency. In part, that’s because the SNB is specifically targeting exchange rates. But it’s also because there’s not enough outstanding Swiss debt for the bank to buy. (Switzerland keeps debt levels relatively low.)

And the SNB’s currency bet is huge.

The bank’s foreign currency holdings have grown to about 75% of GDP.

So the SNB decided to abandon the ceiling on the franc.

That’s what it just announced. In response, the spring-loaded franc shot higher.

The decision caught markets totally off-guard.

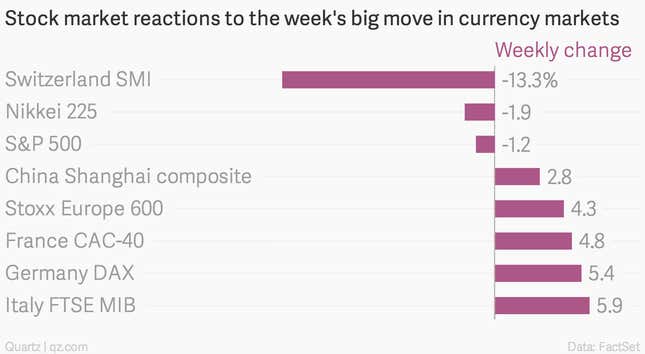

In part, because the rationale for the move is very tough to understand. After all, the strong franc will still hurt the economy, as the performance of the Swiss stock market this week suggests.

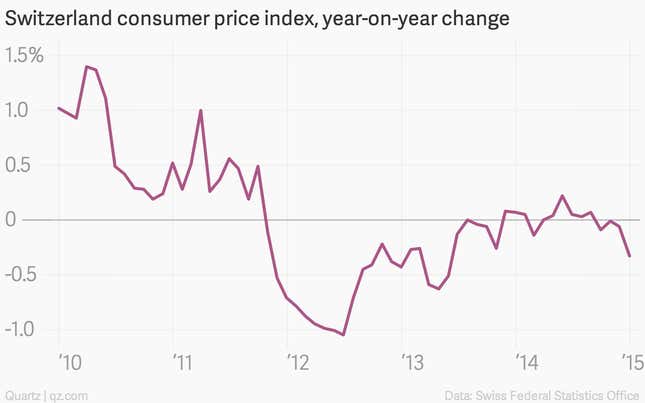

And it likely means Switzerland will slip deeper into deflation.

Prices were already down roughly 0.3% year-over-year in December.

So, all told, what does it mean?

The clearest takeaway: It’s all but a done deal that the European Central Bank starts a bond-buying program of its own at its Jan. 22 meeting. ECB bond-buying is akin to adding more to the supply of euros. If demand is constant, that means prices fall.

The markets took Switzerland’s move this way. The euro weakened sharply. And European government bond yields fell, as expectations grew that the ECB would be buying government debt. On the whole, that’s a very good thing. Europe’s economy is in terrible shape.

Of course, there’s been some collateral damage. The SNB’s decision to suddenly go back on a previous policy it had claimed to be committed to will make markets think twice before taking the bank at its word. That’ll make monetary policy tougher to carry out in the future.

Also, the violence of the move was too much for some market participants—including UK foreign exchange brokerage Alpari—to handle. And there could be further reverberations. For instance, some large European banks have taken to lending in the Hungarian mortgage market—making Swiss franc denominated loans—in recent years. The sudden strengthening of the franc could expose them to losses, after a November law was passed in Hungary allowing homeowners to convert their mortgages back to forints at a rate that looks very cheap after the sudden strengthening of the Swiss currency.

But if you’re looking for scary implications, here’s the biggest: The Swiss National Bank has effectively thrown in the towel in the fight against deflation, which is emerging as the major economic bogeyman of 2015.

The world’s most important economies are all seeing slowing price increases or outright price declines. (China, Europe, the US, Japan) We haven’t seen such a coordinated downtrend their like since the financial crisis and the Great Recession.

Now, a broad-based decline in prices might sound good to consumers. But if the economy were a car, deflation is sort of like driving with the parking brake on. The steady decline in prices makes debt tougher to payback and discourages the kind of capital investment that economic growth relies on. It also pushes consumers to defer purchases in the hopes that prices will be lower in the future. All of that acts as a persistent headwind on growth.

In other words, five years after the worst of the global financial crisis and Great Recession, the world still seems to be tip-toeing toward a deflationary vortex. It will take serious political efforts from governments and central banks to move against the tide. The ECB finally shows signs of joining the fight, which is a good thing. But the SNB’s decision suggests that some governments are giving up and just letting the current carry them away.