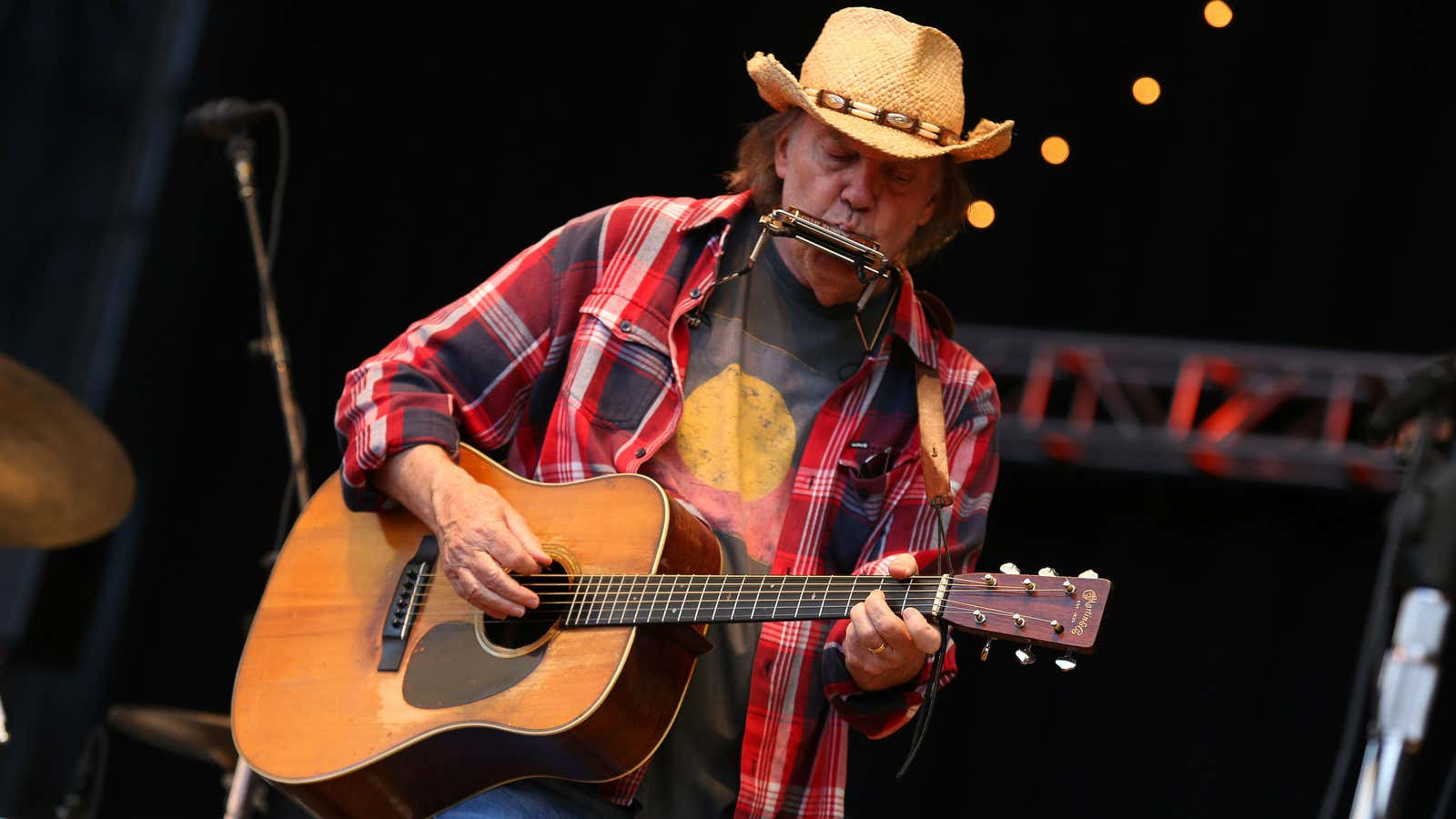

When Neil Young speaks (or sings), people tend to listen.

So when the legendary folk singer outlined his vision for the future of digital music recently, plenty of ears perked up. ”People [are] kind of discovering that MP3s suck,” he declared in an interview with the Wall Street Journal. “It was great to have thousands of songs, but the fact that you could only recognize them, and couldn’t hear them, made it so you weren’t experiencing music.”

Young is leading a crusade among audiophiles to get people to embrace higher quality sound formats in digital music. At the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas, he unveiled his long-awaited new portable audioplayer, Pono, which he launched partly with funding from campaign on the crowdfunding platform Kickstarter. The device will let people listen to high-resolution “lossless” music files, which can be downloaded from the accompanying PonoMusic site.

The device has received lukewarm reviews (at best), but what Young is trying to achieve is still hugely interesting. In effect, he is trying to reverse a weird, counterintuitive trend in the music industry: With each successive market-dominating advance in music technology, the sound quality gets worse.

Vinyl gave way to cassette tapes and then CDs, which gave way to digital downloads, which are now in the process of giving way to all-you-can-eat streaming services such as Spotify. But with the introduction of each new format, the quality of sound has deteriorated. The oldest format (vinyl) had the richest sound quality, while the newest digital download and streaming formats have the worst. CDs fell somewhere in between.

This devolution runs contrary to what has happened in just about every other consumer category, where technology steadily improved the quality of the experience. Take video, where resolutions keep improving. High-definition television is becoming standard, the ultra-high-resolution 4K era is fast approaching. People may be watching movies on smaller mobile screens, but nobody is watching in black and white.

“For some reason music is the only format where people accept something worse than before,” Andy Chen, the CEO of the Norway-based “lossless” streaming provider Tidal tells Quartz. Young expressed similar outrage: “It’s the 21st century. Technology’s job in our civilization is to make life better.”

Chen is convinced that we are at a tipping point for consumer awareness of music quality. He points to growth in premium headphone sales (now a $1-billion industry in the US, and growing rapidly) as evidence that people want better sound and are prepared to pay for it.

Yet as Spotify’s experience attests, convincing people accustomed to accessing music for free to actually pay for it is challenging enough; getting them to pay even more for even better sound (Tidal costs $20 a month, twice the price of Spotify) seems like a long shot.

The market for lossless music is clearly a niche one. Chen estimates that 5% to 8% of consumers in developed music markets would be willing to pay more for a better streaming experience. Free music services such as Pandora Media in the US often argue that services like Spotify and its ilk are for hardcore music fans, which puts Pono and Tidal in the next echelon—the hardest of the hardcore.

But aren’t those the same people who have fallen back in love with vinyl lately? Chen argues that the vinyl renaissance is not an impediment to growth for services such as Tidal. “Nothing can ever replace the physical touch of holding vinyl and the ritualistic act of playing a record on the turntable,” he says.

In any case, vinyl’s revival is arguably more about identity than sound. Something similar can be said for growth in premium headset sales, at least in the case of Beats (which was bought by Apple for $3 billion last year), whose success selling headphones is probably more about image than the headphones’ (famously bass-heavy) sound.

Do people care about sound quality enough to pay a premium for it? Spotify’s Daniel Ek has talked publicly about the possibility of a “higher-priced tier” of subscription that might offer lossless audio quality. So maybe lossless music will reach significant consumer adoption, but whether that’s via bigger, established services such as Spotify and Rdio or newer ones such as Tidal remains to be seen. Streaming music is already an extremely crowded market, and with Apple reportedly preparing to relaunch the Beats streaming service under its better known iTunes brand as soon as March, the moment of truth for many players could be fast approaching.

Still, Chen says there’s room for smaller, specialized music providers. “If we were going to say IKEA is the only furniture player out there because they are the biggest, the cheapest, then there would be no other players out there; but it’s not the case,” Chen says. “It’s similar in music. There is always an amount of people who don’t want to buy CDs; there are some people who are going to be OK with Pandora; there are going to be some people who are OK with ad-funded streaming services. Then there will be others who say quality matters and discovery of music that’s not from an algorithm—that matters. And for that experience, I am going to pay a premium.”