The coming face-off between Greece’s European creditors and the country’s new left-wing government is painted as an epic struggle between intractable foes, but it’s better to think of them as sharing a common goal: Reducing Greece’s daunting debt without admitting it to the rest of Europe.

Greece doesn’t want to be cut loose from the euro zone, but Germany and the rest of the EU will find it hard to keep it in without offering politically unpopular debt relief. As Greece’s new finance minister, Yanis Varoufakis of the Syriza party, put it, “we must offer Mrs. Merkel a way of packaging the new deal that she can then sell to her parliamentarians.”

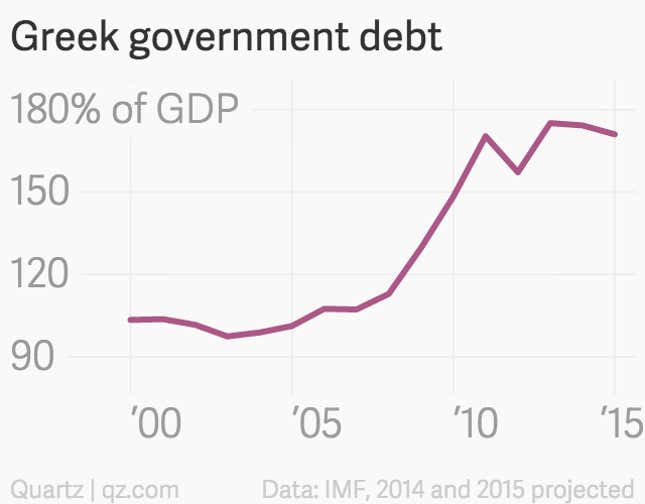

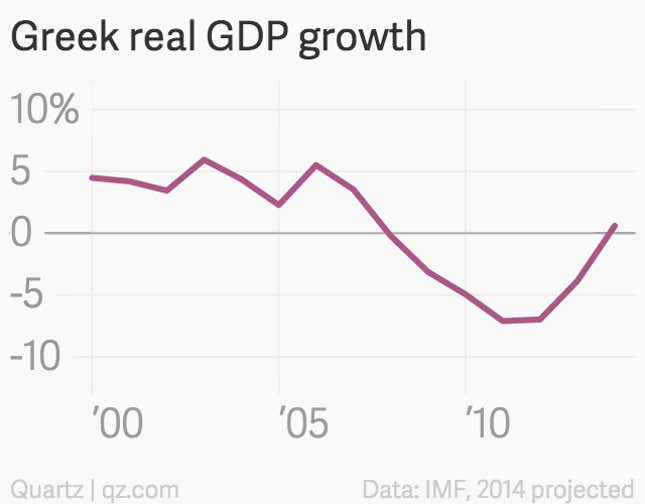

The key thing to realize is that Greece’s problems date back far before Syriza came to spook the markets. The IMF’s most recent projection for Greece’s debt path is that it will decline from a horrendous 174% of GDP in 2013 to a hideous 128% by the end of the decade—but even that’s only if the country generates consistently high economic growth and runs a huge government surplus of around 4% of GDP for several years. Neither seems particularly likely, as private sector economists will tell you and even government ministers concede in private.

A change in tack was inevitable when the bailout program came up for review this summer—if anything, European leaders can be grateful that Syriza’s election win gives them a scapegoat for restructuring. Luckily, most of Greek debt is now held by European governments and will be paid back over very long durations—there are ways to adjust things way out in the future that reduce the overall debt burden without creating a cash crunch or sudden spike in interest rates. Economists at think tank Bruegel offered up a plan to rejigger debt obligations that would cut Greece’s obligations by 17% of current GDP without creating losses for government lenders.

If adopted, such policies will not be called haircuts or debt reduction, even if that’s more or less what they are. Analysts expect they will be preceded by an agreement on Greek fiscal reforms that will include Syriza’s prized relaxation on spending limits for social programs in return for it taking a tough line on the country’s lax approach to taxation. There’s nothing like a left-wing party to implement the the revenue side of austerity by fighting tax evasion.

“There is an opportunity to reach some sort of deal where they can both save face,” Wolfango Piccoli, a managing director at consultancy Teneo Holdings, told Quartz. “You can provide some debt relief on the margin by extending the maturity and everything else, and Syriza pledges some reforms.”

The question for Piccoli—and everyone else—is what Syriza will do to spark growth in Greece’s shattered private sector. As the government and its lenders negotiate high-level, decades-long plans, the fact is that for all the leverage its lenders have over Greece, the only sure thing to put the country back on track is debt reduction—by default or by choice.