Since the European debt crisis first flared in 2010, Greece has been held out as an example of the worst kind of profligate borrower. And it’s true Greece has a bad fiscal record. Government spending was large and inefficient, tax collections nearly nonexistent. Perhaps worst of all, government statisticians cooked the books to cover it up.

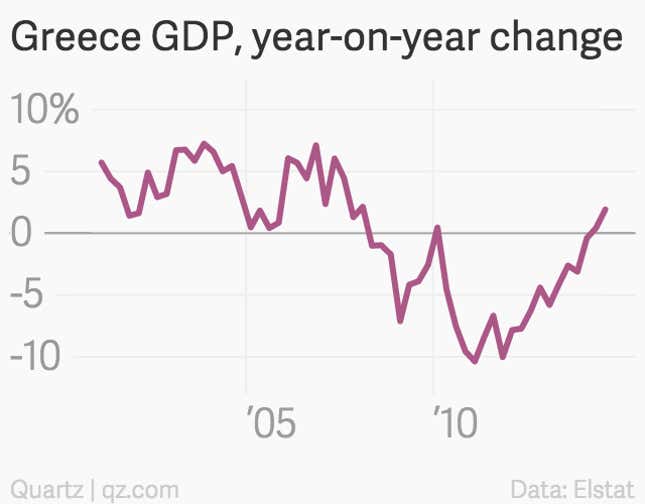

So in the case of Greece, there’s a strong—and understandable—temptation for lenders to see Greece’s resulting debt in moral terms. That’s one of the reasons why creditors find it so difficult to cut Greece’s debt burden by further restructuring it, essentially writing off part of the debt, as part of an agreement with Greece’s new government. That government, led by the leftist coalition party Syriza, rose to power on its promise to renegotiate the terms of the bailout, which has helped destroy roughly a quarter of the Greek economy.

The most rigid moralizing has been done by Germany, for a variety of reasons financial, historical and cultural. (Amateur cultural critics have also long pointed out that the German word for debt—Schulden—comes from the word for guilt, Schuld.)

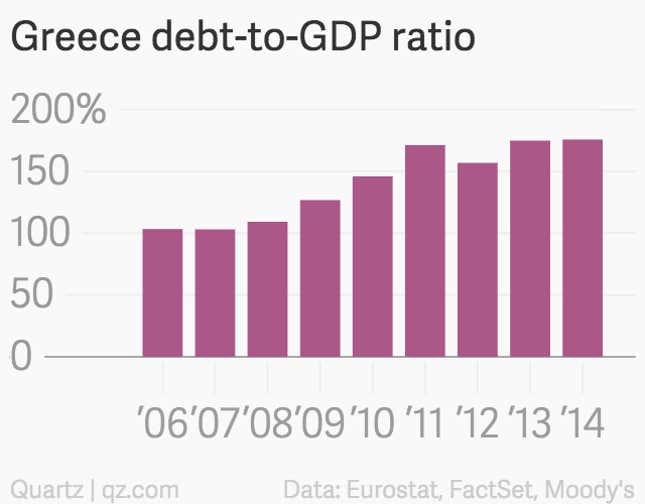

The finger-wagging is profoundly unhelpful. At the end of 2013, Greece owed upwards of €300 billion, or roughly 175% of GDP. It will never pay that debt in full and everyone knows it.

And Germany should know it better than most. After World War I, the victorious allies forced Germany to agree to paying insurmountable reparations as retribution for the war. At the time, John Maynard Keynes warned in his Economic Consequences of the Peace of the futility of such an approach.

“He said, ‘These debts will never be paid, so why not, sort of draw a line under them and go on to the future,'” Robert Skidelsky, a Keynes biographer and economic historian, said in a recent talk hosted by the London School of Economics. “And in fact they weren’t paid.”

First they were famously inflated away in the 1920s in the Weimar hyperinflation. Hitler stopped reparations payments altogether in 1933. Then came World War II, of course, followed by a debt restructuring in 1953. That restructuring did much to contribute the country’s economic recovery after the war, not to mention the economy and stability of the continent as a whole.

You don’t have to look far to find other glass houses. Britain essentially defaulted by going off the gold standard in 1931. Currency devaluation was the preferred mode of default for the French. And while it’s often said that the US has never defaulted on its obligations, that’s not true either. Even if countries don’t stop making payments outright, inflation eats into the value of debts over time, alleviating the burden. The fact is, governments never really pay back all the money they borrow, at least not in real (i.e. inflation-adjusted) terms.

“If one looks at the history of public debt, almost all public debt that’s ever been issued has been, in the end, inflated away or had its real value reduced through restructuring,” said Felix Martin, a macroeconomist and bond investor, who took part in the LSE discussion.

This brings us back to Greece, which, it must be said, really stands out as one of the world’s most prolific defaulters. Reinhart and Rogoff famously noted that the country has been in default for roughly half of the years since it gained independence from the Ottoman Empire in the 1832.

This throws a wrench into the “moral hazard” argument against debt forgiveness, which usually suggests that allowing debtors to stiff creditors encourages such behavior in the future. After all, who were these lenders who thought it wise to extend lend so much money to a country that’s spent half of its existence defaulting on its debts?

We know who they were. They were French and German banks, among others. Many argue that bailout of Greece—and its painful conditions—was actually a bit of backdoor help for the German and French financiers.

Of course, it’s not reasonable to expect creditors to immediately forgive all Greece’s debts. Nor is it reasonable to expect Greeks to stand by while a disastrous economic policy is dictated to them. But the most unreasonable thing of all would be expecting to see the debt repaid in full.