The most often repeated fact about US debt is wrong

As the US debt ceiling looms as the next crisis on the horizon, you’re going to hear it a lot of this.

As the US debt ceiling looms as the next crisis on the horizon, you’re going to hear it a lot of this.

“The government has never defaulted on its obligations…”

“The nation has never defaulted.”

“We’ve never defaulted in our history.”

“It is not acceptable for one faction of one party in one chamber to say, ‘Either we get what we want or we’ll shut down the government,’ or even worse, we will not allow the U.S. Treasury to pay its bills and put the United States in default for the first time in history.”

When it comes to history, never say never. If you go back far enough, almost everything has happened at least once—and sometimes several times. And that’s how it is with US defaults.

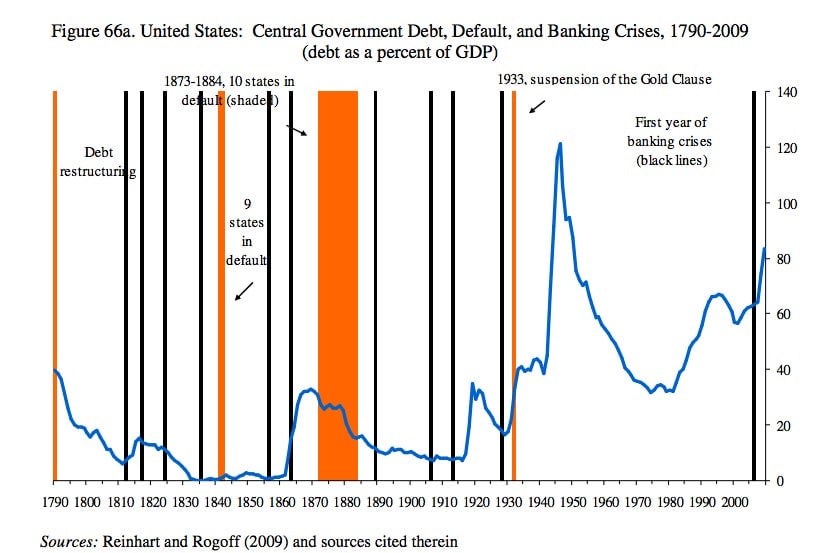

Original sin

The prevailing narrative of US government debt goes something like this. After the US won its independence from Britain in the late 18th century, the country was deeply in debt, owing about $79 million to creditors. Many politicians argued that the nascent country should repudiate its debts altogether and start fresh. Into the breach stepped Alexander Hamilton, who convinced policymakers that the wiser move was to consolidate state debts into a federal pile and then pay debts in full. Hamilton won the day, laying the foundation for the untarnished full-faith-and-credit that serves as the basis for the US’s prized position in global finance to this day.

But what is often glossed over is that the US didn’t just pluckily pay off its wartime debts with a good, old-fashioned dollop of American elbow grease. No, it took the path of modern Greece.

It restructured its debts, with decidedly harsh terms from creditors. In fact, the terms were so tough that an important paper on the topic notes that “a large part of the face value of the debt was effectively written off.” In other words, it wasn’t paid. So was this a default?

Well, as we’ve seen during the ongoing European debt crisis, the word “default” is quite malleable. Technically, Hamilton’s restructuring of the US debt was a voluntary bond swap. And voluntary conversions aren’t always viewed as defaults. But sometimes they are. Just look at Greece, which arranged for a series of “voluntary” conversions of its preposterously large debt over the past few years. Did that constitute default?

S&P says yes, citing two criteria that equate to a default: 1) that investors will receive less than they were promised in the original securities, which was definitely true in the case of Hamilton’s debt swap, and 2) the swap was “distressed” rather than “purely opportunistic.” (It’s not like Hamilton was just taking advantage of a decline in interest rates, for instance.) In his excellent, all-encompassing history of public finance, James Macdonald notes “Hamilton struck a very hard bargain with creditors—one that stretched the terms voluntary conversion and sanctity of contract beyond their true limits.” (Emphasis original.)

Golden handcuffs

The other instance of US default came during the worst years of the Great Depression. In 1933, President Roosevelt devalued the dollar against gold. That violated the so-called gold clause, which required that all public debts be paid in gold coin of a fixed weight. (America’s overwhelmingly pro-Roosevelt Congress simply declared all gold clauses null and void.) The 1933 devaluation effectively amounted to paying off debts with devalued currency, which is widely viewed as a default. In fact, in her exhaustive research on sovereign debt, economist Carmen Reinhart clearly classifies the 1933 devaluation as a domestic default.

The computer glitch of ’79

There have been some other instances of default that were just, well, screw-ups. As the Wall Street Journal’s Jason Zweig recently reminded us, in April and May of 1979—during the height of another debt ceiling debate—computer glitches resulted in the failure of the US to pay $122 million in Treasury bills, which in the hardest sense of the word, was a default. Zweig writes:

The Treasury characterized the problem as a delay rather than as a default. While the error affected only a fraction of 1% of the US debt, short-term interest rates—then around 9%—jumped 0.6 percentage point and the US was promptly sued by bondholders for breach of contract. (Investors were later paid in full, with back interest.)

Correction: A previous version of this post said the US failed to pay “interest” on US Treasury bills in 1979. As Treasury bills are sold at a discount to investors and redeemed at par, they technically don’t pay interest.