Numerous authoritative voices have weighed in with a forecast that, with some help from neighboring Canada and Mexico, the US will become more or less self-sufficient in oil production in a few years and even start exporting. If they are right—has anyone yet learned the sad lessons of mass market enthusiasm?—it will be perhaps only for a flash in time.

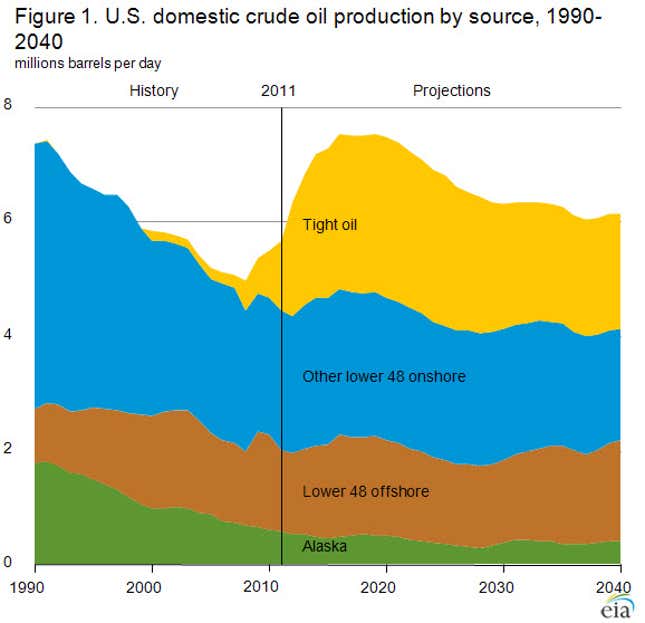

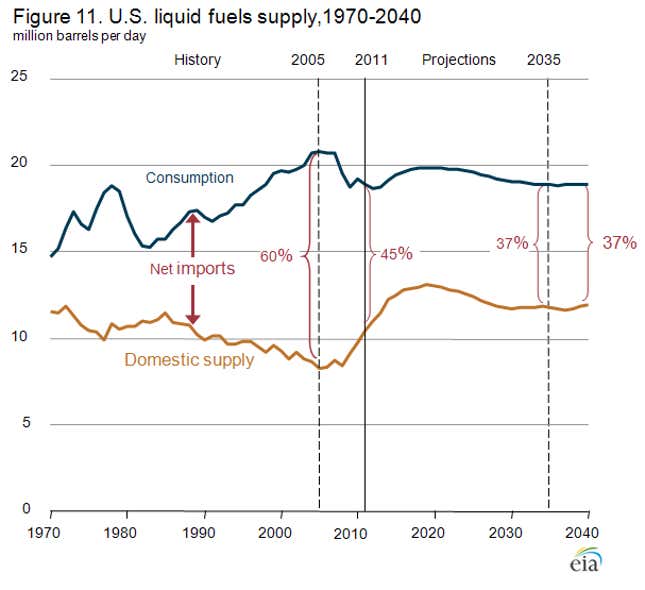

The chart above is from the 2013 Annual Energy Outlook, released Dec. 6 by the US Energy Information Administration, an arm of the Energy Department. As you can see, the EIA forecasts US oil production—driven up by shale or “tight” oil production—peaking in 2019 at 7.53 million barrels a day. US oil imports from Canada and Mexico drop to 34% of consumption, its lowest level since 1986, and down from 60% in 2005.

But the very next year—the peak of forecast tight oil production—production drops to 7.47 million barrels a day. Then it plunges, falling to 6.29 million barrels a day in 2030 and, finally, 6.13 million barrels a day in 2040. As you see in the chart below, imports rise modestly, back to 37% of consumption. Much of the import stability at that point is not because the US is producing more oil—it isn’t—but because Americans are using far less of it.

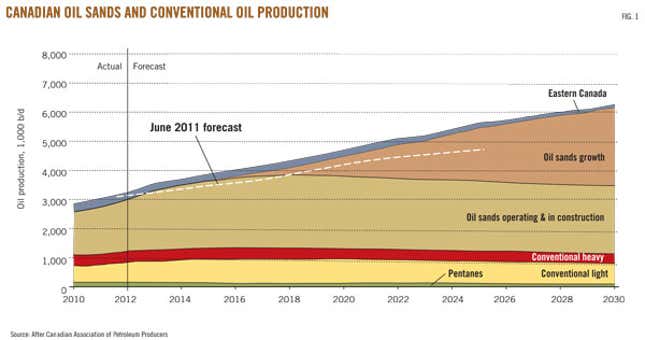

Still, when the see-saw flips, the US will lose one of the main advantages of the oil surge: better balance of payments. Rather than its dollars going to Venezuela, Nigeria, and a bit to the Middle East, they will go to Canada, whose oil sands production is forecast to surge through 2030 and beyond.