China’s debt is finally catching up with it. On Feb. 28, the People’s Bank of China slashed the benchmark one-year rate (link in Chinese) on both loans and deposits by 0.25 percentage points, bringing them to 5.6% and 2.75%, respectively. Though economists had expected a rate cut later this half, many are reading this latest move—and the fact that it comes so soon after two other surprise monetary loosening maneuvers—as a sign that the central bank is vexed about the Chinese economy’s weakening.

But this isn’t about simply juicing lending to rev up growth. The rate cuts highlight the underlying worry that money is dangerously scarce—and that insolvent companies could easily run out of cash.

For decades, China has been the global epicenter of cash inflows, thanks to its huge trade surplus and surging foreign investment. No longer. Rapidly slowing inflation is making it harder and harder for Chinese companies to pay down their huge pile of debts. That disinflation is getting creepily close to deflation, when prices start falling.

That’s pushing China closer and closer to a liquidity trap, says Jianguang Shen, economist at Mizuho—meaning, a state where cash-hoarding makes interest rates unable to spur the economy.

Here’s a breakdown of the problem:

Industrial profits are tanking

Industrial profit fell 8% in December 2014, compared with the previous year, notes Mizuho’s Shen. The dead weight is coming from state-owned enterprises (SOEs). While private-sector profit leapt 6.9% in 2014, compared with 2013, those of SOEs plummeted 7.8%.

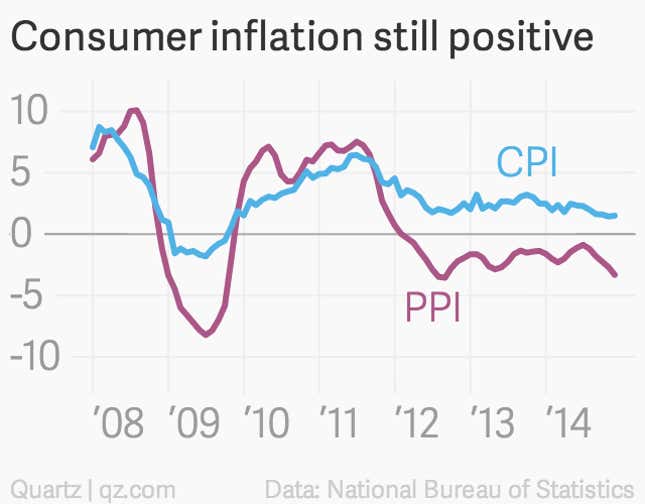

Deflation hits manufacturing

In a desperate bid for cash, SOE industrial companies are producing more than than the economy demands, causing producer price inflation to keep nosediving.

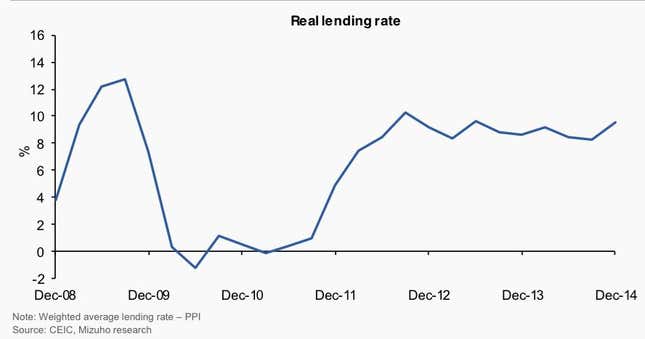

Borrowing costs are rising

In effect, those falling prices are making it more and more expensive for SOEs to pay back loans.

The solution for SOEs is to keep taking out more loans. But while that new lending might prevent a rash of alarming bankruptcies, it also isn’t helping the economy grow. Private companies might help juice growth, but since banks tend to lend to SOEs, they’re not getting the capital they need.

Consumers aren’t buying

Domestic consumption is supposed to be gradually kicking in as an engine of growth. However, it’s been worryingly weak. For instance, retail spending during last week’s Chinese Lunar New Year celebration—a time when consumers tend to splash cash—slowed to 11% versus the same period in 2014, a drop of 2.3 percentage points. Growth in disposable income is also slipping fast.

The PBoC tries again

As Andrew Batson and Chen Long of GaveKal note, the two rate cuts are “quite large in aggregate.” For instance, before November, Chinese firms faced annual debt-servicing costs equal to 14% of GDP; now they’re closer to 12.5%.

That said, November’s much bigger rate cut didn’t help lower borrowing costs much, possibly because so much of that extra liquidity flowed into the stock market.

What next?

With monetary policy already seeming to have little effect at reviving growth, the big hope for the Chinese economy is that the government will up its fiscal spending target, says Bloomberg economist Tom Orlik, from 2014’s 2.1% of GDP to something closer to 2.5%. Stay tuned: the government will reveal its budget plans at the National People’s Congress meets this week.