Fewer peer-to-peer lending dollars are actually coming from your peers.

Peer-to-peer lending was conceived as a way to democratize finance, by using technology to bring borrowers and lenders together. Individuals could make their pitches to borrow money or offer credit without the involvement of institutional lenders. But in the past three years, Wall Street banks, private equity funds, and asset managers searching for higher financial returns have plowed into the these marketplaces, raising concerns over the path forward for what some peg at a $1 trillion market.

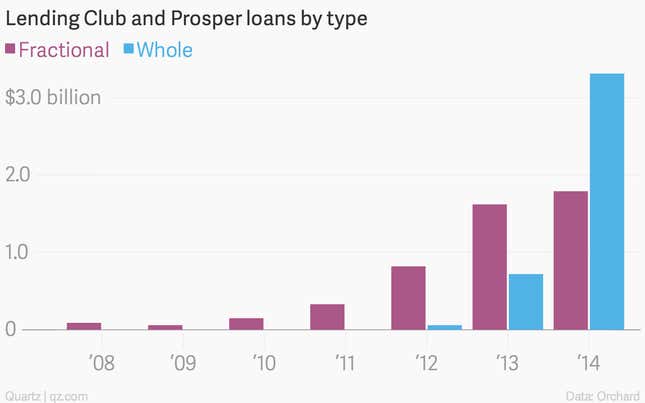

A look at the loan makeup of America’s best known players, Lending Club and Prosper, shows that all of the loans made on the two platforms in 2008 were fractional, meaning individual lenders came together and each put in as little as $25 toward a loan, according to Orchard Platform, a startup that links institutions to marketplace lending.

Now, only 35% of the loan dollars are coming from fractional loans. In 2014, the other 65% of the more than $3 billion loans on the two platforms came from investors snatching up whole loans, which are almost always made by institutional investors rather than individuals.

“Peer to peer is a misnomer for this industry,” says Matt Burton, CEO of Orchard, which is backed by Wall Street heavyweights like former Morgan Stanley CEO John Mack and former Citigroup CEO Vikram Pandit.

Outside of Lending Club and Prosper, the picture is even more skewed toward Wall Street banks and asset managers like BlackRock. Institutional investors have been piling into dozens of new marketplaces to fund everything from real estate and student loans to boats and medical bills—an area small investors have been largely shut out of due to US Securities and Exchange Commission rules that limit these offerings to so-called “accredited investors” who make at least $200,000 a year or have a net worth of more than $1 million (excluding their primary residences).

Today, an SEC committee charged with making it easier for small businesses to raise money approved recommendations to grow the number of people who can invest in crowd-funded investments—by expanding the definition of “accredited investor” to include investors who meet a sophistication test, regardless of their income or net worth.

If adopted, that small change could open up investment opportunities to more people. And as Kiran Lingam, general counsel of crowdfunding startup SeedInvest wrote in a comment letter to the SEC this week, that could help the industry “focus on facilitating main street capital raising rather than creating another Wall Street secondary trading market.”