The incentive problem at the heart of peer-to-peer lending

You might not remember the originate-to-distribute model, but there’s a good chance you remember its effect on the economy.

You might not remember the originate-to-distribute model, but there’s a good chance you remember its effect on the economy.

Originate-to-distribute represented a vast change to the way home lending traditionally worked, and it was all the rage in global finance until 2007, when its shortcomings started to show.

Traditionally, banks had loaned money to borrowers, and slowly collected the principal and interest as it was repaid overtime. Under the originate-to-distribute model, banks made the loans, but didn’t collect the money themselves. Instead they sold the loans into the secondary market, and collected the cash from investors upfront. The idea was that this would free up credit for additional lending, while freeing banks from the risk that borrowers might never pay them back.

There were a few problems with this. For starters, since mortgage originators didn’t have to worry about getting paid back by the borrowers, they began lending wildly. (Lax regulation didn’t help either.) Secondly, the investors who bought the loans—usually packaged into securities—didn’t have the expertise to evaluate the risks. Instead, they relied on problematic ratings issued by credit-rating firms. Of course, everyone had elaborate, data-driven models that forecasted that these assets would perform just fine. But the models completely broke down under the strain of the groaning US housing market, once things went south.

Why bring up such an old story?

Because the originate-to-distribute model lives on. In fact, a high-profile—if tiny—financial entity entirely based on the model is going public today.

Shares of Lending Club, the largest US peer-to-peer lender, soared more than 50% in their debut today on the New York Stock Exchange. The warm reception the offering received is a coup for the technology investors who financed the firm. Many have eagerly greeted the appearance of companies like Lending Club, and rivals such as Prosper, as competitors who might potentially disrupt the US financial system.

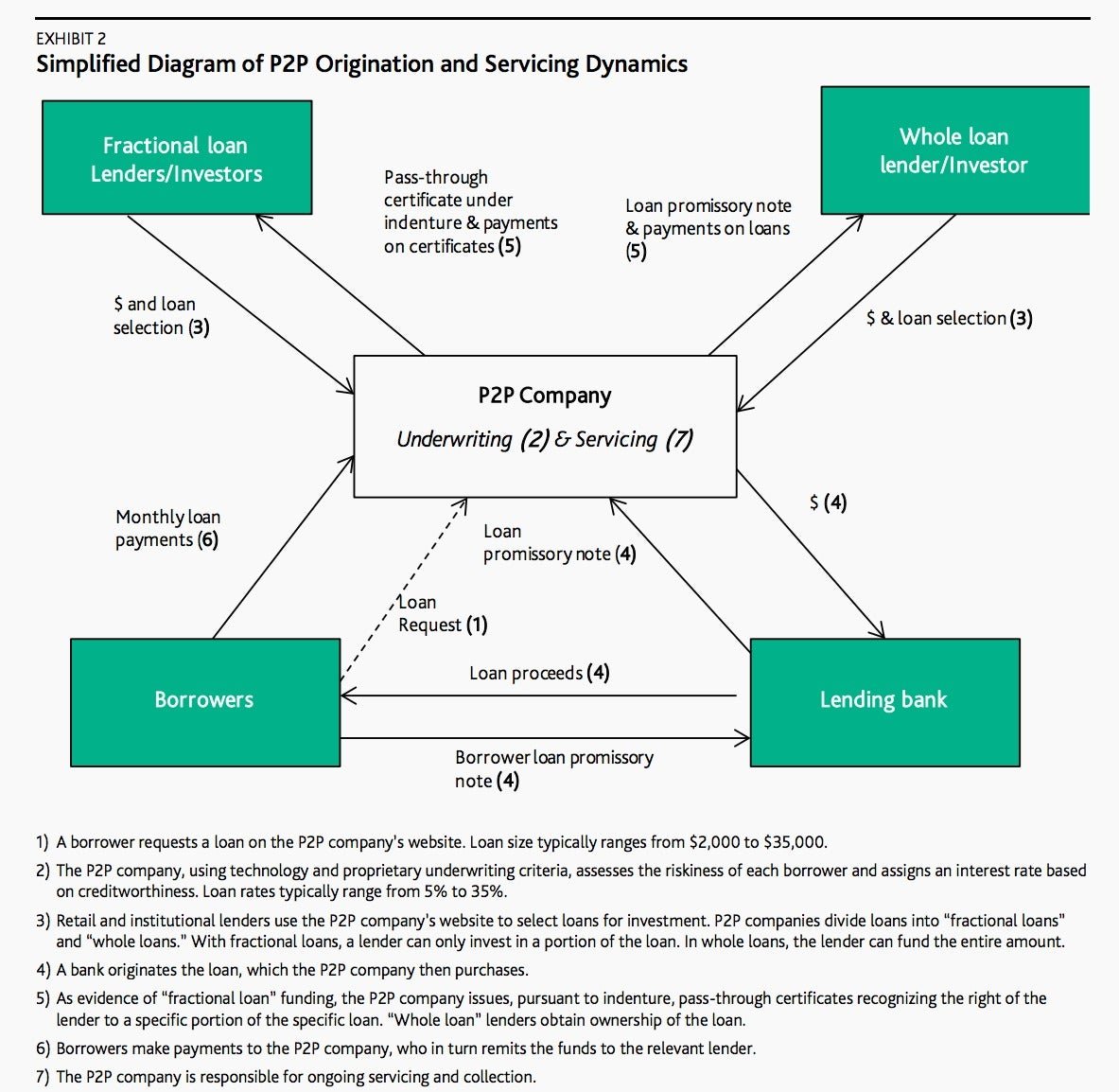

Despite its name, Lending Club isn’t a lender itself. Rather it uses its technology to connect borrowers to lenders. A bank in Utah actually originates the loans. LendingClub collects the money for the loan, and hands it over the the Utah bank. The bank then forks over the loan to LendingClub, which breaks it up and issues “payment dependent notes” to the lenders, which entitle them to their share of the principal and the interest as the borrower pays back both over time. Here’s how Moody’s described the model, and its concerns about it:

P2P companies are essentially using an originate-to-distribute business model, there is a risk that their interests will not be aligned with those of investors. P2P companies might loosen underwriting standards in order to increase origination volume. Without a financial interest in the loans, however, the P2P companies would experience little negative impact if loans they originate were to default.

Of course, no one thinks that the next financial crisis will come from the peer-to-peer lending space. For one thing, it’s truly a tiny slice of the global financial system. And some would argue that the incentive problems in the originate-to-distribute model have been blown out of proportion. (To wit, auto and credit-card finance companies using similar models had nowhere near the problems experienced in the mortgage market during the crisis.)

Peer-to-peer lenders, for their part, would have to be tremendously shortsighted to go wobbly on credit standards in search of higher fees. After all, their platforms depend on lenders having enough confidence to use them.

But there is a niggling misalignment of incentives inherent in these businesses. The Yale Journal on Regulation explained it like this:

Traditional lenders, such as retail banks, mediate credit risk. If they lend out deposits and the borrower fails to pay, they still owe depositors money. P2P lending platforms, however, do not mediate credit risk. They only pay out on “borrower payment dependent notes” if the borrower pays. Hence, the platforms that advertise and enforce the loans have little direct stake in loan repayment.

To be sure, peer-to-peer lending could bring real benefits both to borrowers and to investors looking for higher rates of return on their money. For those benefits to be realized, though, the industry will have to mind the contradiction at the heart of its business model.