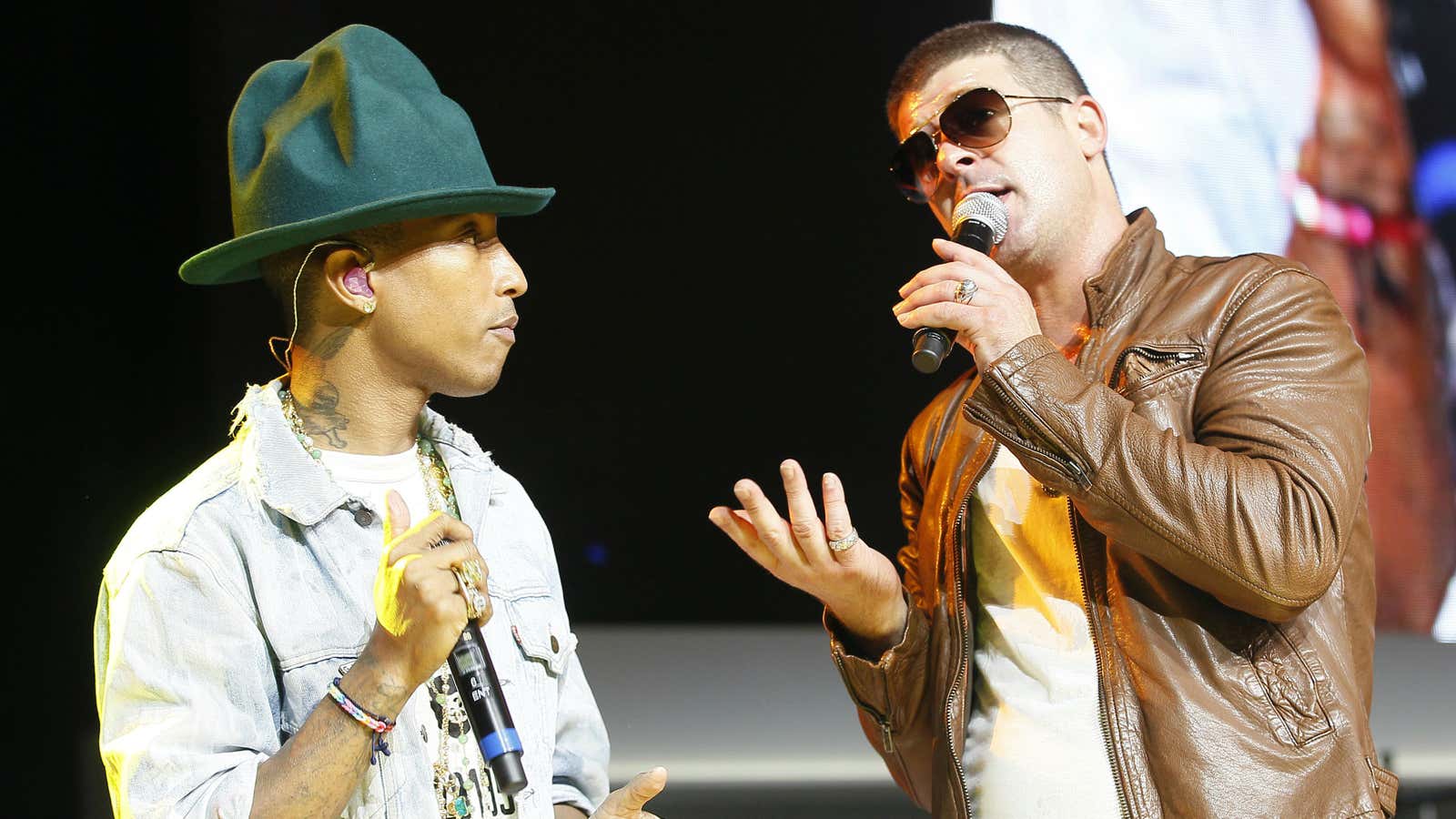

A Los Angeles jury ruled today that the hit 2013 song “Blurred Lines” infringed on the copyright for Marvin Gaye’s 1977 party jam, “Got to Give It Up,” and ordered “Blurred Lines” composers Robin Thicke and Pharrell Williams to pay more than $7.3 million to Gaye’s family.

Even if you love Marvin Gaye and hate Robin Thicke’s misogynist and vaguely rapey song, the verdict sets a terrible precedent, and could have a chilling effect on musicians trying to create new songs.

“Blurred Lines” does not take any lyrics or melodies directly from “Got to Give It Up,” but when you listen to the songs together it’s clear that they sound kind of similar. Lawyers for Thicke and Williams argued that they tried to evoke “that late ’70s feeling” of Gaye’s song, but that those elements are not copyrightable.

The jurors disagreed—even though the judge banned them from listening to “Got to Give It Up” except as a mash-up that combined a disembodied rhythm track with Thicke’s vocals.

What will happen if a song’s “feel” or “vibe” becomes copyrightable, and songwriters can sue musicians for evoking the same mood? Here’s Parker Higgins, director of copyright activism at the Electronic Frontier Foundation:

When we say a song ‘sounds like’ a certain era, it’s because artists in that era were doing a lot of the same things—or, yes, copying each other. If copyright were to extend out past things like the melody to really cover the other parts that make up the ‘feel’ of a song, there’s no way an era, or a city, or a movement could have a certain sound. Without that, we lose the next disco, the next Motown, the next batch of protest songs.

The last few decades have seen a number of court cases, mostly in the United States, restrict the rights of artists to incorporate the work of their predecessors. In 2005, the music publishing company Bridgeport—which also played a minor role in the “Blurred Lines” case—won a court ruling that decreed that no sampling, no matter how brief or altered, could be done without the copyright holder’s pre-approval. The US copyright system is so tangled that the late musicologist Alan Lomax, through an unlikely chain of covers and samples, is a co-author of the Jay-Z song “Takeover.”

In a TED talk last year, producer Mark Ronson—whose recent chart-topper “Uptown Funk” evoked early ’80s funk just as “Blurred Lines” referenced the late ’70s—talked about how musician have always paid homage to (and sometimes outright pillaged) their predecessors, citing samples in hip-hop from groups like the Beastie Boys:

They heard something in that music that spoke to them that they instantly wanted to inject themselves into the narrative of that music. They heard it, they wanted to be a part of it, and all of a sudden they found themselves in possession of the technology to do so, not much unlike the way the Delta blues struck a chord with the Stones and the Beatles and Clapton, and they felt the need to co-opt that music for the tools of their day. You know, in music we take something that we love and we build on it.

The “Blurred Lines” verdict may ultimately be appealed—Thicke and Pharrell are considering their options—and in any case the $7.3 million verdict won’t break the bank: They each earned more than $5 million from the song, according to courtroom testimony. But the true cost will come due when an unknown musical genius tries to create a new song that evokes a particular era, and is sued into oblivion because it “kind of sounds the same” as a song that came before.