The glitzy skyscrapers of Hong Kong’s financial center stand in stark contrast to a dirty grey industrial building in the city’s run-down Kwun Tong district. Yet nine floors up, in an office bereft of any form of signage, a new artificially intelligent investor is taking shape.

This trading robot, developed by a team of academic roboticists, mathematicians, and ex-bankers, is the brainchild of fledgling hedge fund Aidyia, which has been seed-funded by venture capitalist Emanuel Breiter. Scheduled to start trading US equities this year, the team hopes it will deliver returns on the three years and millions of dollars it has taken to build, by turning huge swathes of financial and linguistic data into unique investment strategies.

“It’s seeing patterns that aren’t easy for the human mind to wrap itself around,” said Aidyia’s co-founder and chief scientist, Ben Goertzel.

Computer-assisted trading is nothing new. But Aidyia and other firms—including hedge fund giants Bridgewater Associates and Renaissance Technologies—hope to create intelligent software that can teach itself to adapt to changing market conditions, without guidance or instruction from humans.

Financial traders may not be the first people Elon Musk, Bill Gates and Stephen Hawking were thinking of when they expressed their recent concerns about AI’s threat to the human race. But if companies like Aidyia succeed, the human trading profession could well be one of its first casualties.

From algorithms to machines that can learn

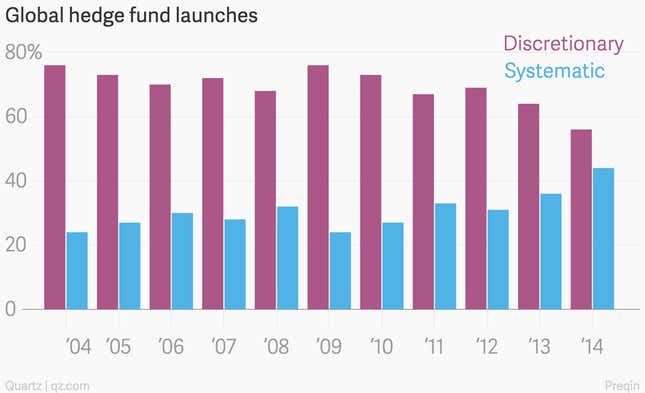

Last year more than 40% of new hedge funds were “systematic,” meaning they used computer models for the majority of their trades, according to data provider Preqin—the highest percentage ever.

The closely-related field of algorithmic trading is designed to react extremely quickly to market changes. The algorithms seek out and exploit small windows of trading opportunity, often measured in minute fractions of a second. So many orders on the US stock market are now placed by automated algorithms that the Securities and Exchange Commission is looking for ways to regulate them as it does the rest of Wall Street.

These algorithms may work at superhuman speeds to identify tiny windows of trading opportunity, but ultimately they do exactly what they are programmed to do by humans.

Not so the AI systems. One of the quintessential things that sets apart the AI systems being designed for financial trading is their ability to learn and adapt.

Most quantitative trading, as it is currently practiced, relies on a human being to develop a mathematical model to identify trading opportunities. The model is then updated by hand to adapt to new markets or changing conditions. For an AI, conversely, humans develops the initial software, but the AI itself develops the model and changes it over time.

The trading robot developed by Aidyia ingests vast amounts of information, including news and social media, and uses its reasoning powers to recognize connections and patterns in the data. It then uses those patterns to make predictions about the market, which it translates into buy and sell orders—all without any direct human involvement.

Silicon Valley’s artificial brain drain

The latest advances in applying artificial intelligence to financial trading have been fueled by Silicon Valley, where companies like Google have invested heavily in machine learning to enable projects like self-driving cars. Bridgewater’s AI team is being led by David Ferrucci, who formerly managed the IBM team that developed Watson, the computer “Jeopardy!” champion that recently also created recipes for a cookbook.

Goertzel spent years researching and applying AI and cognitive science in universities around the world before turning his talents to banking. Looking more hippy than hip, he has long, curly hair, crumpled jeans, and John Lennon glasses that are a jarring contrast to the designer-suited bankers who normally work at Hong Kong’s hedge funds. But he is ultimately chasing the same profits.

He’s just doing it by using an artificial intelligence system that can find patterns in the “humungous” volume of market information and data that the human mind “cannot possibly comprehend.”

“Human emotions have certain predictable patterns to them,” he told Quartz. “So it’s amalgamating the predictions of tens of thousands of different predictive patterns that it identifies…and that’s where the AI gets the advantage.”

From back-testing to reality

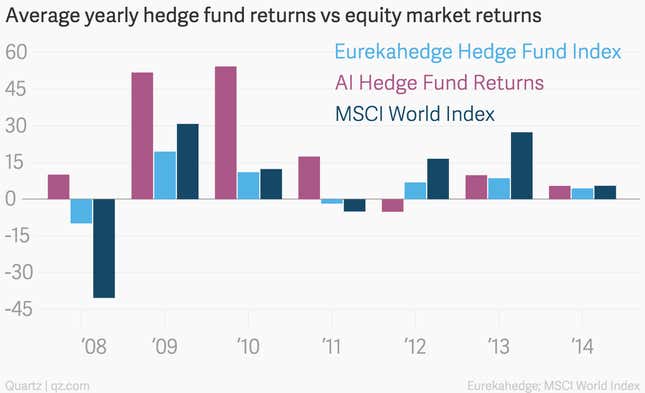

Hedge funds that use AI to drive their investment decisions have outperformed average industry returns every year for the past seven, except for 2012, according to industry data provider, Eurekahedge.

But it’s a risky industry and the average masks the wide range of returns, with some AI hedge funds making large profits, and others failing spectacularly.

“There are some very disciplined AI programs with strong emphasis on downside protection [a strategy to prevent financial losses] that have been around for more than five years and have delivered double digit returns, and then are others with really volatile returns that the average hedge fund investor would shy away from,” noted Mohammad Hassan, an analyst with Eurekahedge.

This volatility has made itself abundantly clear in each of the last three years, where the overall performance of global equity markets has easily outshone the average hedge fund, AI-driven or not.

Aidyia has conducted extensive testing of its AI system using more than ten years worth of historical data, and CEO Ken Cooper claims it has averaged a very healthy 25% year-on-year return.

Yet historical tests do not always translate into real-world success, noted one senior Wall Street banker, who was not authorized by his firm to speak on the record, but said he would never invest in a hedge fund like Aidyia based on back-tested data alone. “History has never been a good predictor of the future,” he said.

“Money grows in the dark”

Some in the industry, like Gerrit van Wingerden, managing director with Tora, a trading technology group that works extensively with hedge funds and asset managers, believe the success of the AI funds may in fact be underestimated due to the secrecy that surrounds these types of businesses.

“I firmly believe that money grows in the dark and a lot of people who are doing this (AI investing) are keeping their mouths shut as they don’t want people to find out what they are doing and how they are doing it,” he said.

Aidyia’s executives don’t hesitate when asked if AI will eventually replace human traders. “We meet people (in the finance industry) all the time and honestly if I say a robot will be running asset management sometime in the future people go yeah, yeah, I see that future,” said Cooper.

Goertzel nodded in agreement. “You don’t get too much pushback on the idea that AIs will be operating the financial markets in our lifetime,” he said.

Georgia McCafferty is a Hong Kong-based freelance journalist who writes about business, finance, and education.