The popular stereotype of geekdom generally involves some image of a guy with glasses, his pale skin irradiated by the glow of the computer screen as he draws up complicated charts to demonstrate which is stronger, the Hulk or Green Lantern’s giant green magic fist. It’s a sad, ugly, image—and Sam Maggs means to change it.

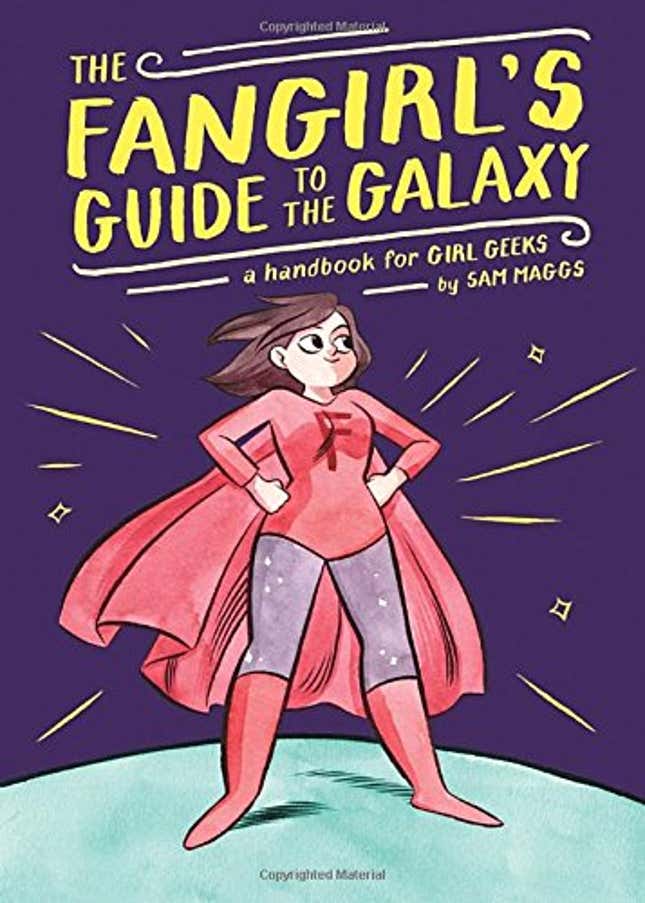

Granted, altering stereotypes isn’t exactly the stated goal of Maggs’ The Fangirl’s Guide to the Galaxy: A Handbook. Like the title says, The Fangirl’s Guide is a guide to all things geeky, designed specifically with the girls who love those geeky things in mind. It provides guidance on navigating sci-fi cons (comfortable shoes, everyone), visiting comics shops, writing fan fiction, and even getting geeky tattoos (“Don’t ever get an in-home or ‘stick and poke’ tattoo. They’re dangerous and never look as good as professional ink.'”)

But amidst all that advice, it’s impossible to miss the fact that Magg’s guide presents a different vision of fans than the stereotypical one. Specifically, the fans in Maggs book are girls.

“I think women have always been into these things, but we’ve always felt excluded from the spaces where people would talk about them,” Maggs told Quartz. “Before social media there were forums, and ladies weren’t usually welcome there, and we have traditionally felt intimidated going into comic book shops, or video game stores where our cred might be questioned, or we might feel unwelcome by a male employee.”

Women have always been a part of geek fandoms or fan communities—sci-fi, comics, fantasy, and more. They just haven’t always been visible.

The advent of social media, though, has made it possible for fangirls to find each other, which has in turn made them more willing to be vocal about their fandom—which has made fangirls more able to find each other, and so on. The internet, Maggs said, “has been very helpful for women in the geek world because we’ve been able to find and form our own communities on Twitter or on Tumblr, building things like The Mary Sue” (a geekgirls fan site where Maggs is also an associate editor.)

The growth in the visibility of women has started to change the fandoms themselves, in numerous ways—particularly when it comes to making them less exclusive and less sexist. On social media, Maggs says, “we’re able to speak directly to Marvel, directly to comic book companies, directly to video game companies, directly to movie producers and say this is what we want, we have money, we’re here, we’re waiting to buy it, make it for us! And in a lot of cases they’re listening.”

Marvel comics, in particular, has taken a number of steps to try to reach out to female fans, most notably Maggs says, with titles like Ms. Marvel and female Thor, which are outselling their male counterparts. Ms. Marvel is Marvel’s top digital seller according to editor Sana Amanat, suggesting that many women find it more convenient, or more comfortable, to buy comics online than in the comic store.

Women are also changing what it means to be a fan, or what kinds of activities fans participate in. Cosplay— dressing up as a favorite sci-fi or anime or comics character—has become a major pastime, and even a major draw, at many conventions. Some cosplayers become celebrities themselves, and can be paid to come to cons as guests; the vast majority just enjoy dressing up, and/or taking pictures of others’ costumes.

“I think cosplay is cool because it’s one of the rare areas in the geek world where women completely dominate,” Maggs said. “That is really a female-built industry, for women by women. And it’s girls taking control of their own bodies and in some cases, of their own sexuality, and expressing their fandom in a way that suits them or that they’re comfortable with, and that’s really great.”

The growing power of female fans hasn’t come without some cost, however.

Among male fans, and older fans, the rise of cosplay, and of female fans in general, has lead to backlash. A few comics artists and professionals have complained about cosplayers taking up too much space at conventions, for example. And of course the gamergate movement in the video game industry has been an often vicious, sometimes dangerous, attempt to shut down women who want games to be more inclusive and diverse.

Old school fans, it would seem, fear that women will be a corrupting, ruining force. They worry that modern female heroes like Thor will replace old male favorites, or that the cosplayers taking each others’ pictures will distract from folks trying to sell their fan art.

But as Maggs explained, adding diverse perspectives actually makes for more interesting stories. “Like when we say, ‘don’t fridge a female character, don’t kill off a female character to motivate the male character’ —that’s kind of lazy writing. Can you not find another way to motivate your male character that you have to fall back on, ‘let’s kill his mom!’ That’s what we’re complaining about. Just do better.” Women make up half the human race—including their perspectives makes for richer, better stories.

But more than that, the presence of women in fandoms serves as a constant counterpoint to the dreary stereotype of sexless, gross guys huddling in their mothers’ basements. Geeks were never really like that to begin with: all sorts of people have always loved Dr. Who and Mr. Spock and Wonder Woman. The greater visibility of fangirls helps geekdom in general, by showing that there’s no one way to be a fan.

Ultimately, The Fangirls Guide is a guide, yes, but it’s also a sign that the old stereotypes are finally dying out. And good riddance. “I don’t see [fandom] becoming a complete boys club again,” Maggs told me, “because we’re here and we’re not going anywhere. We like what we like.”