It isn’t the first time that HSBC has threatened to leave London, but it might be the last.

The bank’s exasperated chief executive, Stuart Gulliver, sounded pretty serious on May 5 about moving the group’s headquarters out of the British capital, following on from similar hints by chairman Douglas Flint last month. The latest gripes about the cost of being based in London came after HSBC reported a decent set of first-quarter financial results.

The bank’s future financial results, and especially its ability to boost dividends for shareholders, are under threat from unpredictable, avaricious regulators, Gulliver seemed to suggest.

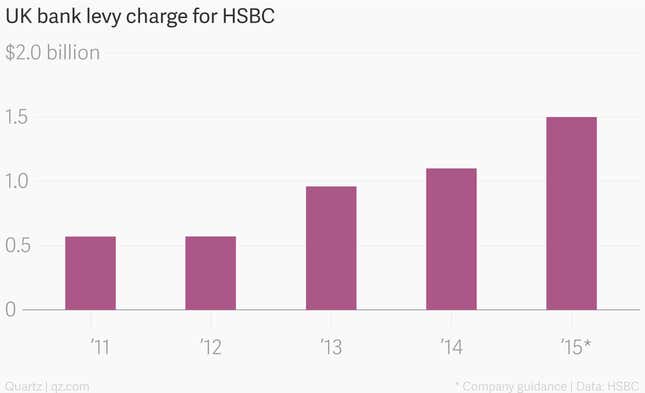

The bank levy bites

A special bank levy introduced by the UK in 2011 cost the bank $1.1 billion last year, and will rise to $1.5 billion this year thanks to the latest in a series of hikes to the levy rate, which is based on the size of a bank’s balance sheet. The tax forces banks to “make a contribution which reflects the risks they pose to the financial system and the wider economy,” the government says.

The chief exec also took issue with the British government’s plan to “ring fence” retail banking businesses in the country into separately capitalized subsidiaries. The point is to set them apart from the investment banks and racier operations that so-called “universal banks” like HSBC also run in search of synergies. “The UK has rejected the concept of universal banking,” Gulliver said.

That’s why shareholders have been urging him to up sticks and move the bank’s seat to a more amenable jurisdiction, Gulliver said. Next month, HSBC will announce the criteria it will use to determine where it should locate its legal base, with a final recommendation to be made by the end of the year—a “non-trivial decision,” points out the chief exec.

A return to the bank’s roots?

Although the bank has not specified exactly where it would move if it couldn’t stand London any more, the front runner is surely Hong Kong. After all, that is where the bank was originally founded in 1865. It left for London in the early 1990s, as the city-state neared the end of its time under British rule.

The bank generates the bulk of its profit in Asia, and Gulliver said a key consideration for the bank’s possible relocation will be a “20-year view on where the fastest economic growth is going to be in the world,” which also suggests an Asian base over options like the US or elsewhere in Europe.

Gulliver himself is a permanent resident of Hong Kong, which has an income tax rate that’s far lower than the UK. (He pays UK taxes on his worldwide earnings, a spokeswoman said earlier this year, minus a Hong Kong tax credit.) Moving HSBC’s headquarters to Hong Kong, which has a flat corporate tax rate of 16.5% a year and many other tax advantages, could unlock $14 billion for shareholders in coming years, a Sanford Bernstein analyst estimated.

Others say that HSBC’s angst is of its own making. Gulliver himself admitted that if the bank were making “a hell of a lot more money,” the pinch of the UK bank levy would be less of an issue. And let’s not forget that HSBC’s persistent legal problems saddled it with some $3.7 billion in fines, settlements, and related provisions last year, a charge far higher than the government levy.

Unwinding an ill-judged global expansion is also proving plenty expensive. Set against HSBC’s many self-inflicted wounds, the complaints about costly and intrusive British regulation ring somewhat hollow.

History lessons

What’s more, one of the very reasons that the bank shifted from Hong Kong for London the first time may give bank executives pause.

HSBC’s re-evaluation of its Hong Kong headquarters started soon after the deadly 1989 crackdown on student protests in Tiananmen Square, and was directly influenced by that tragedy, historians say. “Tiananmen Square was a huge event,” David Kynaston, co-author of The Lion Wakes: A Modern History of HSBC, said during a recent book reading in Hong Kong. It “undeniably” had an impact on HSBC’s decision to relocate to the UK, he said.

Hong Kong has been remarkably stable and violence-free since the 1997 handover to Beijing—arguably more so than London, where HSBC was among the companies targeted during riots in 2011. But tensions are rising in the city as Beijing’s authoritarian government increases its pressure on quasi-democratic Hong Kong.

The city’s government is already run by Beijing-friendly top officials. The pro-democracy protests that shut down part of central Hong Kong for months last year were sparked after Beijing reneged on a pledge to allow a committee that represents the city’s population to nominate candidates for the city’s top government. (Instead they will be picked by a pro-Beijing group of business leaders). Protesters are gone from the streets, but the stage is set for more demonstrations.

While the UK’s politics look messy now, how Hong Kong’s will evolve is anyone’s guess. So far, a pro-Beijing government has mostly left the city’s businesses alone. But if Chinese president Xi Jinping’s corruption crackdown on the mainland and Macau is any sign, the landscape would change dramatically if Beijing turns its attentions to corporate Hong Kong.

One sign of how different things are in Hong Kong, compared even with the worst of the UK’s ugly political fights: While targeting corrupt officials, Xi has also taken out political rivals, several of whom have been sentenced to death.

Could Hong Kong’s regulator handle HSBC? Or Beijing’s?

Although the territory’s financial watchdog said it has a “positive attitude“ towards HSBC relocating there, it has never supervised a bank of its size, with assets worth around nine times the city-state’s entire economy. Gulliver dismissed this question from an analyst on a conference call, noting simplistically that China as a whole has “rather a large GDP.”

Global bank watchers aren’t so sanguine. Last year, the International Monetary Fund questioned the Hong Kong Monetary Authority’s independence, pointing out that a little-noticed rule gives Hong Kong’s chief executive blanket authority to override the regulator whenever he wants. Given that the chief executive is guaranteed to be a pro-Beijing lackey, that could put HSBC in an uncomfortable situation.

For its part, Beijing would probably welcome a move by HSBC, seeing it as affirmation of the country’s status as a global economic power, especially as the central government is pushing more private banks to open on the mainland. But how would the authoritarian government deal with HSBC, when their own state-owned banks are direct tools of monetary and fiscal policy?

Ultimately, Beijing’s influence over HSBC could make the supposed meddling of British officials look tame by comparison.