Uber, the fast growing, controversial and incredibly popular ride sharing app, is on a roll at the moment.

The Wall Street Journal (paywall) reported late on Friday (May 8) that the company is in talks to raise another $2 billion in funds, in a deal that would value it (if you accept all the caveats and fuzzy math embedded into these private market valuations) at $50 billion, making it the most valuable startup on earth.

Why is Uber raising this money? The company only just raised funds, and it is not clear to what extent, if at all, it has burnt through that cash. The prevailing narrative in the tech press seems to be that it is raising again simply because it can. Or as the New York Times put it, the company is taking advantage of the ”overwhelming amount of investor interest” it is fielding at the moment.

That huge interest no doubt reflects a highly buoyant investment climate for tech startups. But it also reflects the fact that Uber is growing like crazy. Documents leaked to Business Insider in December suggest the company’s revenue is increasing at a truly staggering pace. One of its biggest backers, Google Ventures boss Bill Maris, has described Uber as the fastest growing startup he has ever seen.

Uber hasn’t responded to a request for comment from Quartz on the fundraising.

Estimates for Uber’s potential market size vary wildly but it’s pretty clear the app-enabled ride hailing/sharing business is a lucrative one. So if we accept that Uber has already run away with that market, it raises the question: is there anything that can derail this business?

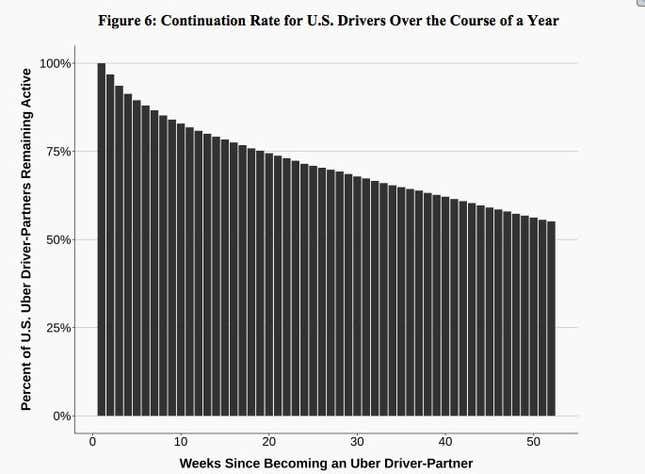

One thorn in the side of the company is labor relations. The company’s business model depends (at least until autonomous cars get here) on an army of participating drivers. And as the above chart from a study commissioned by Uber shows, the company has a problem retaining them.

Uber’s drivers are more akin to contractors, but want to be paid and treated like employees. The more money the company raises, the more pressure it will undoubtedly face to bow to their concerns. Just how big of a problem this becomes remains unclear.

Meanwhile, the biggest problem facing Uber, in the short term at least, is hubris. There are numerous worrying suggestions of the company’s callous business practices and public relations blunders: comments by a senior executive about how it should dig up dirt on journalists; allegations it has tried to sabotage competitors’ businesses and fundraising activities, privacy concerns and criticism about its surge pricing during terror incidents, to name a few.

In this light, Uber’s greatest threat may not be Lyft or the global taxi lobby, but Uber itself.