This post has been updated.

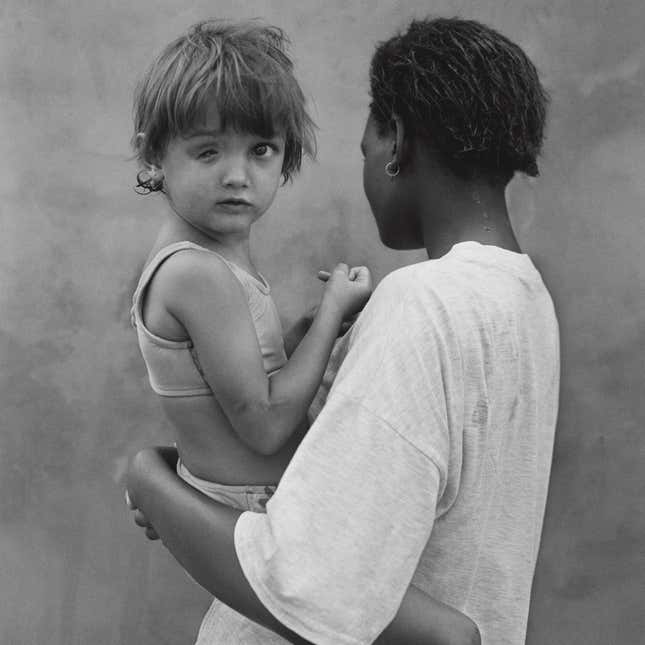

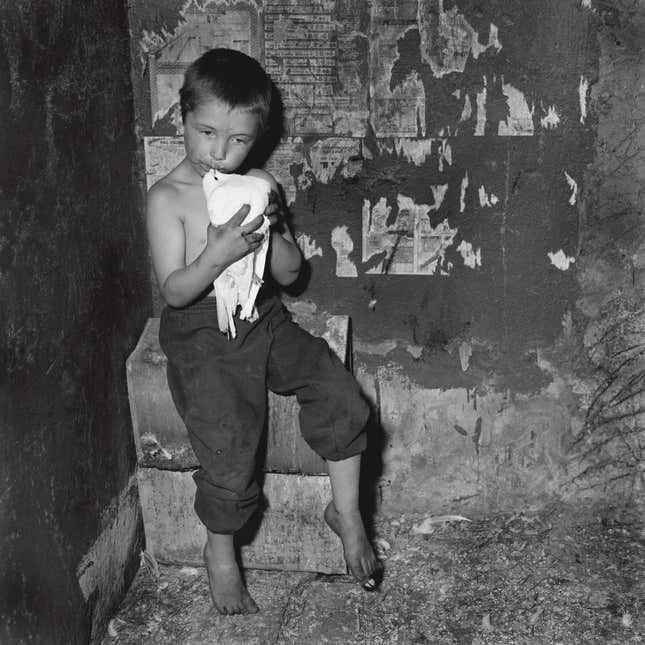

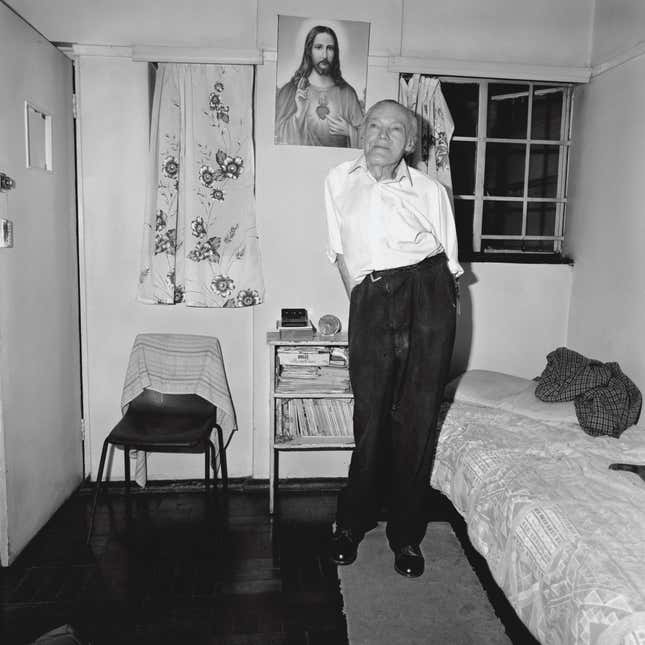

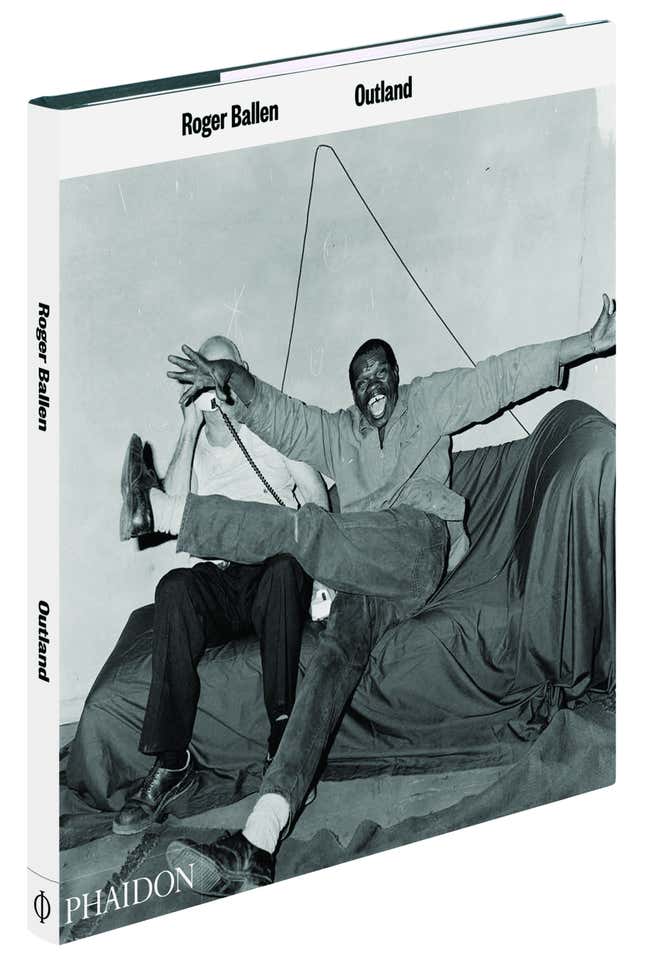

Weird, tender, and unsettling, photographer Roger Ballen’s 2001 book Outland is devoted to people at the far margins of South African society. The introduction in Phaidon’s newly-released second edition recounts a typical conversation between Ballen, who describes himself as “a doctor, a priest, a welfare worker, a financier,” and his subjects:

What are you doing?

Nothing.

How do you feel?

I don’t know.

Any plans?

Nothing.

Nothingness is repeatedly depicted in the US photographer’s images—bare walls; gaping holes where eyes and teeth should be; long, empty days—and the theme speaks to an overlooked reality of life in parts of post-apartheid South Africa.

Created during the five years after South Africa’s first democratic government was elected in 1994, the photos in Outland focus on poor, mostly white communities around Johannesburg, as the structures of apartheid crumbled around them. Ballen’s subjects don’t appear particularly threatened by the social shift—there’s little in the way of economic or social capital left to lose.

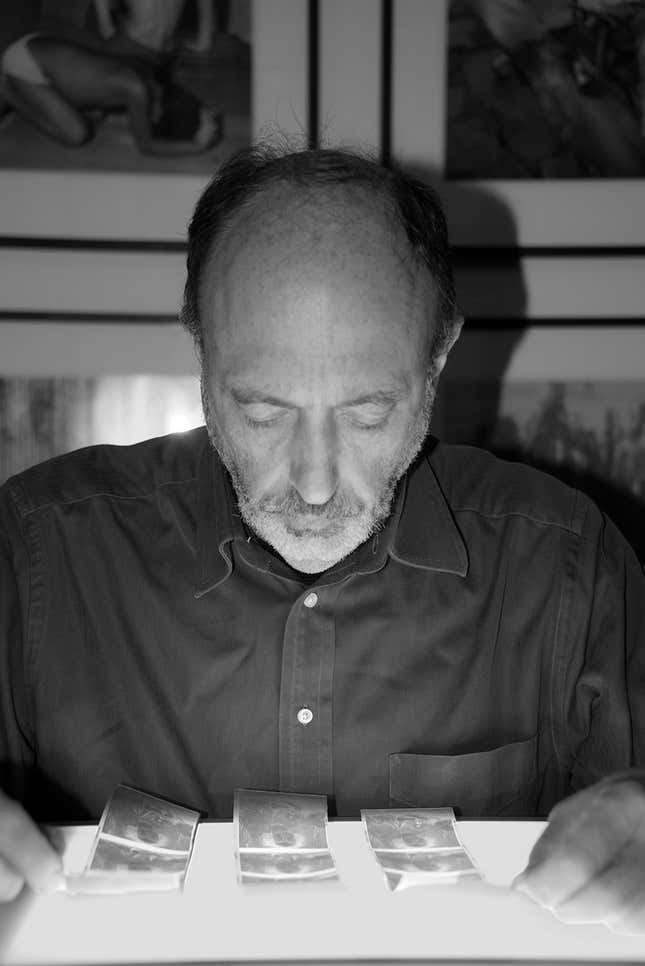

The book’s first edition was controversial in South Africa, recalls Ballen, who’s now 65. “There were basically two reactions—one from South Africa and the other from the rest of the world,” he tells Quartz. “During the apartheid regime, whites had tried to organize themselves into being organized and functional, and then I showed a part of white society that wasn’t organized at all. People in South Africa felt that I was was misrepresenting what the white population was about. And in the rest of the world, it became a very important book.”

The passage of time seems to have made Outland more palatable locally. Ballen, who dove into pop culture a few years ago by directing the music video I fink you freeky for the Cape Town rave-rap group Die Antwoord, figures it helps that his fan base now skews too young to remember South Africa’s 1990s.

“To be honest, now I’m seen more as a hero,” says Ballen. “Everyone in South Africa ran away from me, and now they say, ‘It’s an honor.'”

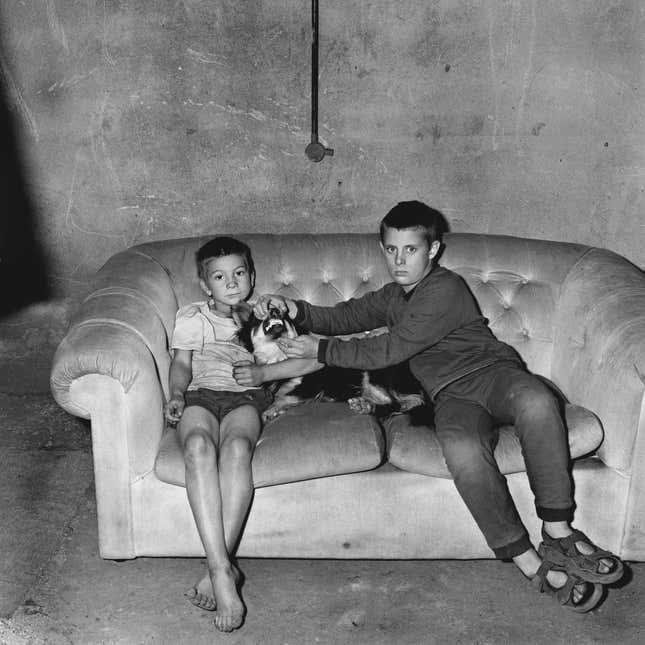

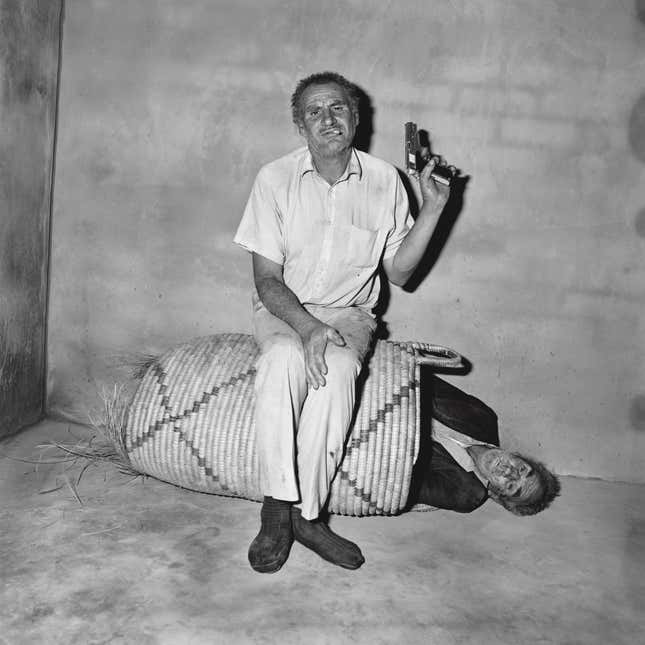

Unlike studies of poverty and marginalization by photographers such as Diane Arbus, Ballen’s Outland is more creation than documentation. Subjects dance and grimace with props. They strike unlikely poses. Pets feature prominently. ”I was trying to show that chaos was more prevalent in the world than order,” says Ballen.

While it’s impossible to divine how much of each scene is directed by the artist behind the camera and how much comes from individuals’ personalities and eccentricities, Outland’s tableaux are indisputably choreographed. Fabric and electrical wires drape as backdrops in homes and outbuildings.

Evocative of classical portraiture, elaborate posturing and props have been appropriated by very different artists, such as painter Kehinde Wiley, to comment on issues of race and class. Ballen famously rejects any clear interpretation of his work: “A photo should have a complexity to it that you can’t put in a box. Clear form, complex meaning,” he says. Nevertheless, Outland, too, could serve as social commentary: a darkly playful reminder of South Africa’s deep class divides, despite the country’s hard-won democracy.

Critics argue that the photos show a kind of exploitation by Ballen himself. He has after all built a career on coaxing the poor and marginalized to perform for faraway collectors and readers. Whether all that adds or subtracts from Outland’s power to disturb is yet another matter of opinion.

Outland (2015, 2nd edition, $69.95) is published by Phaidon. We welcome your comments at ideas@qz.com.

Update: an earlier version of this post incorrectly listed the price as $49.95.