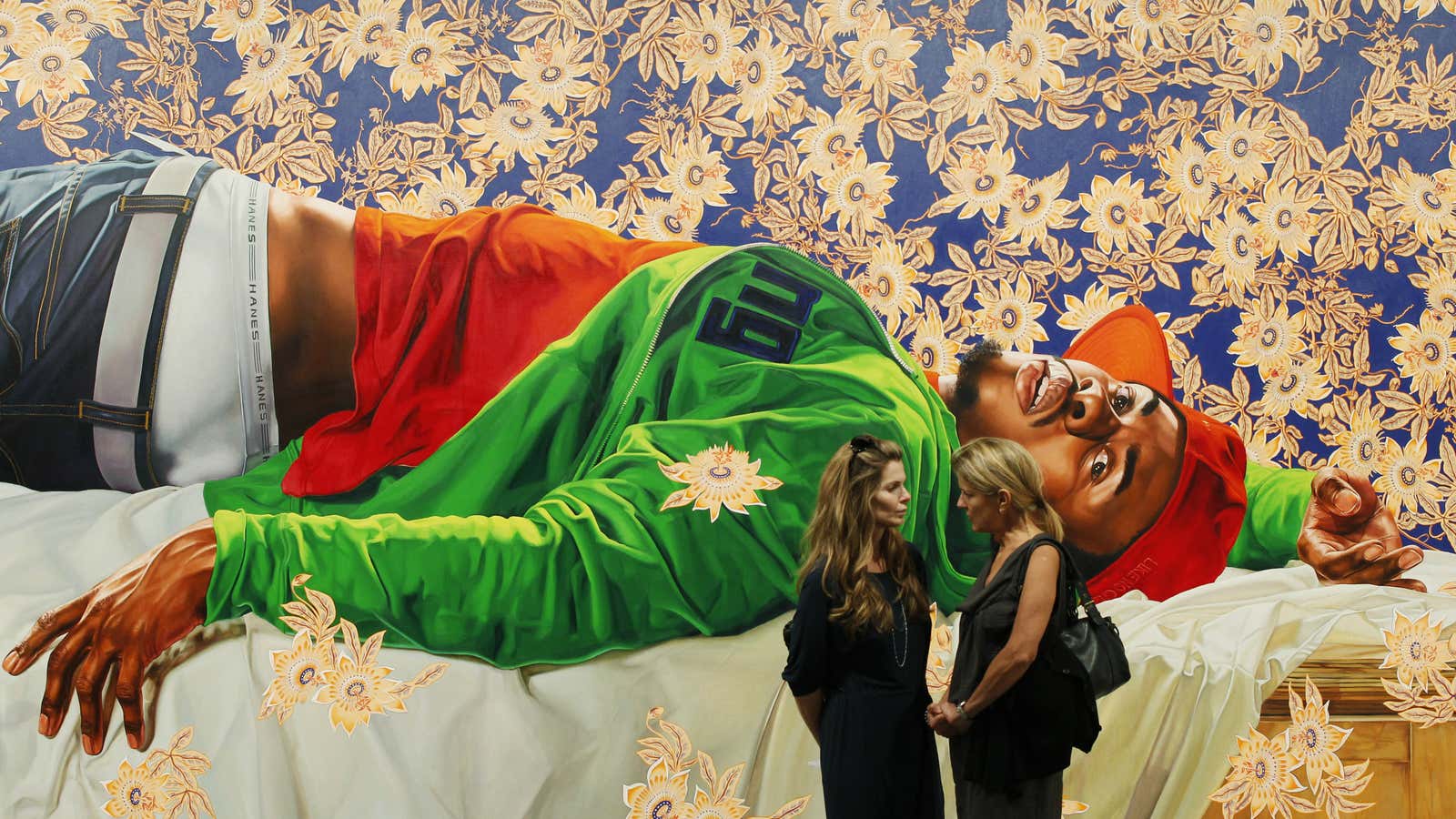

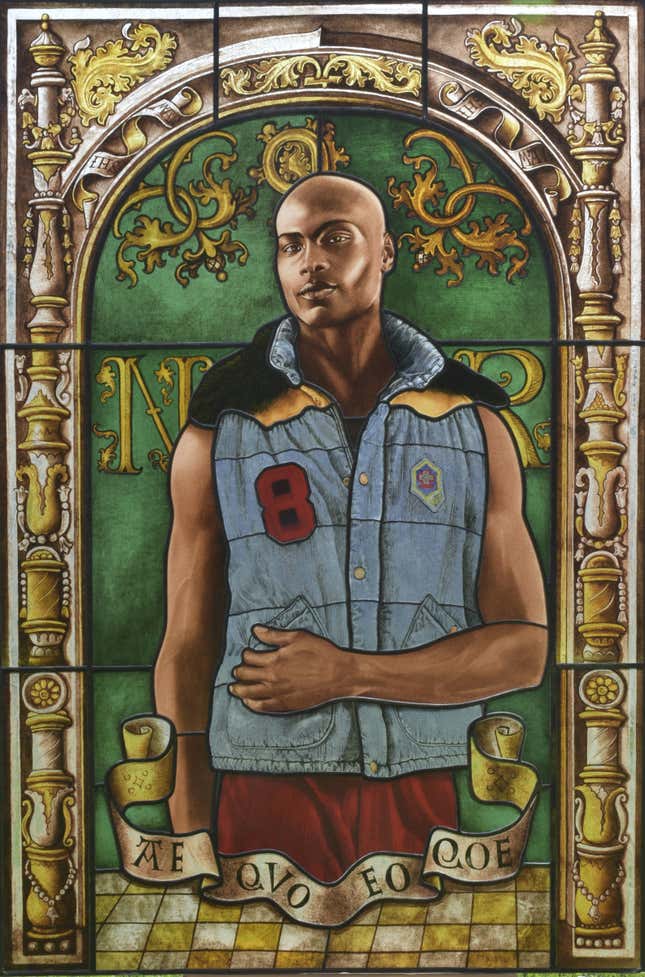

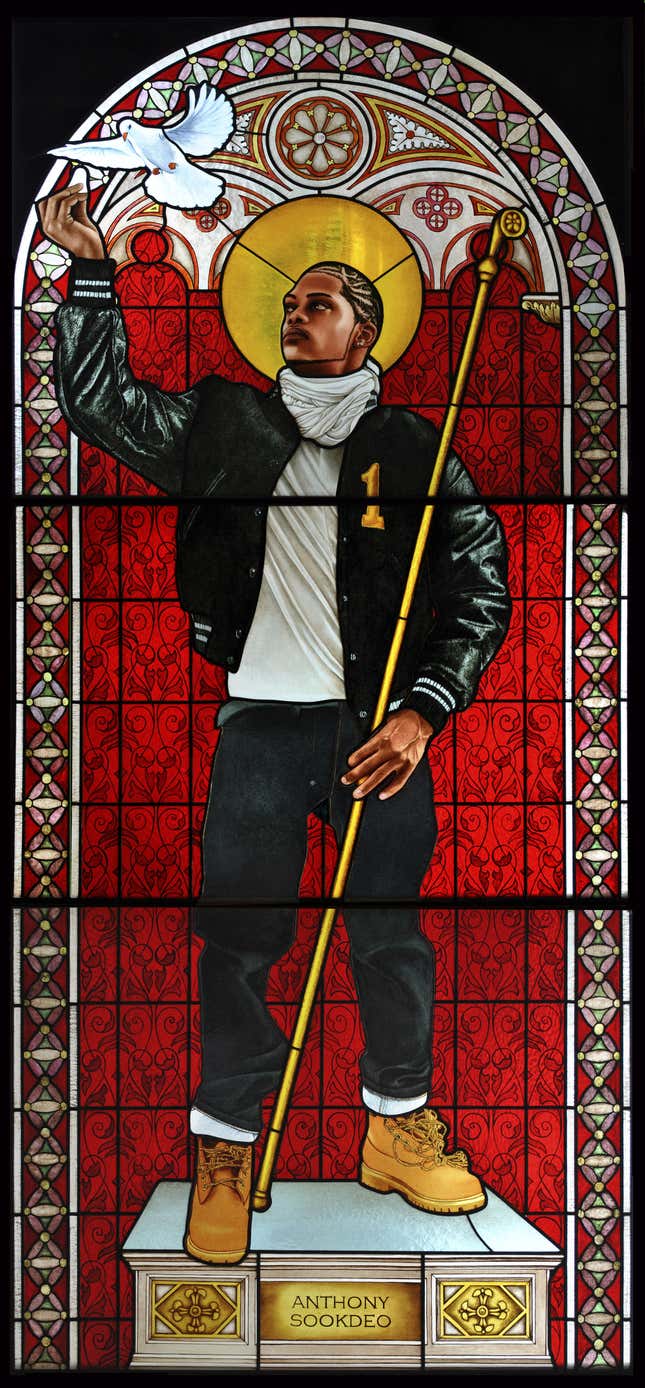

LL Cool J à la John Singer Sargent. Ice T as Napoleon by David. A black man in a green hoodie with Hanes tighty-whities peeking, posing like that scandalous languorous marble sculpture at the Musée D’Orsay. On the surface, Kehinde Wiley’s work may seem like familiar pastiche, or the art world’s best efforts at an internet meme.

The 37-year old portrait painter, who was awarded the US State Department Medal of Arts in January and whose retrospective recently opened at the Brooklyn Museum (paywall), is best known for recasting European masterpieces with African American subjects.

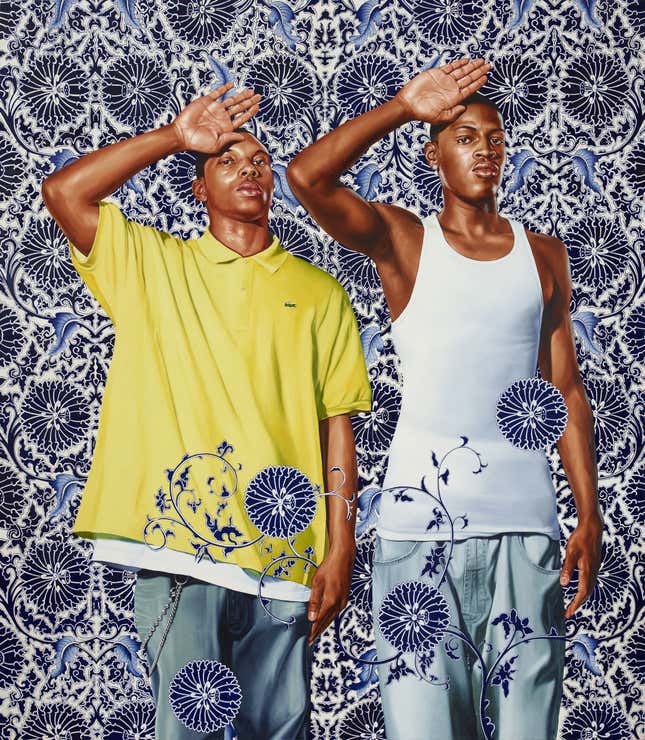

The artist conducts “street casting” in places like Harlem in New York City, Port-au-Prince in Haiti, New Delhi and Mumbai in India, and South Central, Los Angeles where he grew up. Wiley recruits subjects, mostly strangers, to select a pose from a book of European Old Masters and reenact it for a portrait.

Born to a Nigerian father and an African American mother, the background of his paintings reference African cloth patterns, snaking through the composition to give further clues on his subject. For example, in this reinterpretation of David’s Napoleon, Wiley embeds tiny swimming sperm in the red background, as a reference to African male virility, or potentially, promiscuity.

Cribbing from titans of Western art like Jacques-Louis David, Édouard Manet, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and Titian, Wiley creates hyper-realistic portraits, imbuing his subjects with the similar air of dignity or vainglory found in old paintings. “I use French Rococo influences, with its garishness and vulgarity, to complement the flashy attire and display of ‘material consumption’ evident in hip-hop culture,” he has said.

The formula is not new. Old/new, high/low juxtapositions are au courant in contemporary art (examples: Kara Walker‘s race commentary via graphic silhouettes, the self-portraits of Senegalese photographer Omar Victor Diop or even the COLORS magazine cover featuring a black Queen Elizabeth from 1993), as well as on social media.

But unlike the internet meme designed to be consumed in one-calorie visual bites, his work rewards the attentive viewer on several levels. Wiley, who has a master’s degree from Yale University, actually upends several traditions in the art canon.

In addition to swapping out traditional portraiture subjects (read: established white aristocrats) with contemporary African Americans, the artist also overturns the relationship between the court portrait painter and sitter, conflating the power and cachet of the client and creator. Contrast that with works executed under, say, Henry VIII, who relied on Hans Holbein to mask his corpulent, aging image with a commanding portrait.

Wiley’s work has been exhibited all over the world, and has even made appearance in the popular TV series “Empire.” But also unlike a meme, his impeccable larger-than-life portraiture is best encountered in person. A retrospective of Wiley’s work is currently on exhibit at the Brooklyn Museum in New York and will be traveling around the US.