Breathe a big sigh of relief. China’s housing market finally seems to be reviving. The 7% rise in national property sales in April was the first growth in 15 months. Prices for Soufun’s 100-city index nudged into positive territory last month too, as the recent relaxation of property-purchase rules and monetary loosening took effect.

This is heartening news for China’s economy and finances. Counting the indirect benefit to other sectors—like cement, glass, metals and furniture—real estate and construction fuels as much as 30% of GDP, according to Gavekal, a research firm. Fitch, the ratings agency, estimates that outstanding loans using property as collateral add up to 22 trillion yuan ($3.6 trillion), about four-fifths of the total.

However, even if the housing market recovery gains momentum, it’s unlikely to buoy growth the way it once did. The Chinese government’s expectations to keep growing by 7% until 2020 will probably prove too optimistic. Gavekal’s Andrew Batson and Rosealea Yao made this point in a Oct. 2014 note.

According to their analysis, what powered the Chinese construction bonanza in the last decade was “upgrading” (meaning, when families sell their existing home to buy a fancier, bigger place—perhaps to make room for a new child, aging parents, or maybe just a man-cave). China now has enough decently-sized homes that prospective upgraders don’t need to turn to new construction to meet their needs. Instead, demand for new construction will be limited to migrant influxes to cities and replacement of old homes. That means Chinese housing demand overall peaked back in 2011, wrote Batson and Yao.

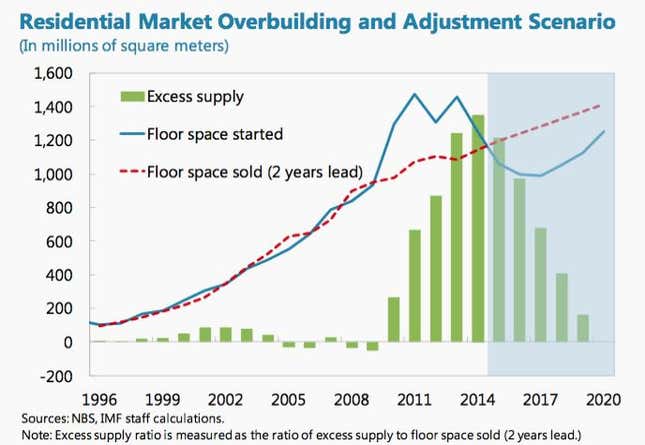

This might begin to explain the alarming buildup in inventory. Recent IMF research found that it would take until 2020 for demand to finally sop up housing oversupply.

A closer look at inventory reveals an even more worrying trend: The diverging fortunes of big and small cities. The recent pickup in sales and prices is limited chiefly to first-tier cities (Beijing, Guangzhou, Shanghai, and Shenzhen) and a handful of other coastal metropolises. In smaller cities, an already enormous overhang of excess apartments continues to swell. These cities now account for more than 70% of China’s total property inventory (in terms of floor space under construction or completed), according to a recent Nomura note:

Unfortunately, the great urban migration that will increasingly fuel new construction demand just isn’t happening for those smaller cities. The populations of first-tier cities rose 1.2% a year from 2011 to 2013, a rate of increase more than three times faster than in third- and fourth-tier cities, wrote Nomura. On top of that, many of these smaller cities are in dire financial straits, having borrowed heavily to fund their property binge.

So as real estate kicks out, how will the country—or, more accurately, its poorer cities—grow? The Chinese government will likely turn to the second barrel of its stimulus shotgun, infrastructure. In the last couple of months, it has already announced huge budgets for new transportation projects. According to Nomura, the withering finances of smaller cities could make them priority destinations for new infrastructure investments, even though investing in bigger cities makes more economic sense.