This is China’s third housing market downturn in seven years. Here’s what’s different this time

China’s housing market is sure looking ugly these days. In July, prices of new homes in 70 major cities fell 0.9% versus a month earlier, a sharper drop than in June, and the fastest fall in five years.

China’s housing market is sure looking ugly these days. In July, prices of new homes in 70 major cities fell 0.9% versus a month earlier, a sharper drop than in June, and the fastest fall in five years.

The market doesn’t appear to care very much, though, notching up a sixth straight week of gains for the benchmark index, the longest winning streak since Mar. 2012. In a recent note, JL Warren Capital explained that the stock market “has once again become convinced that problems in the housing market are gone,” thanks largely to government stimulus measures, loosened credit, eased mortgaged conditions, and relaxed home-purchasing rules .

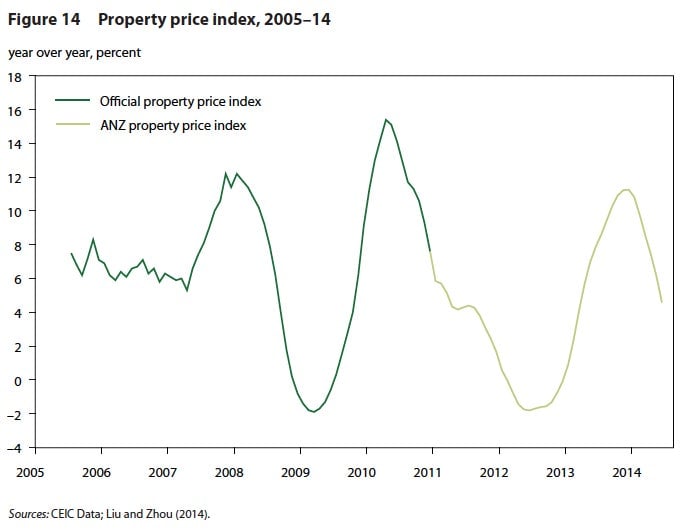

This confidence might come from the fact that the government has arrested sharp market corrections before.”There is no need to become overly worried,” says Li-Gang Liu (pdf), fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics. The property market has gone through two previous cycles, says Liu—one from 2007 to mid-2009, the next from mid-2009 to mid-2012.

But this time there’s something different, argues David Cui, strategist at Bank of America/Merrill Lynch, in a recent note.

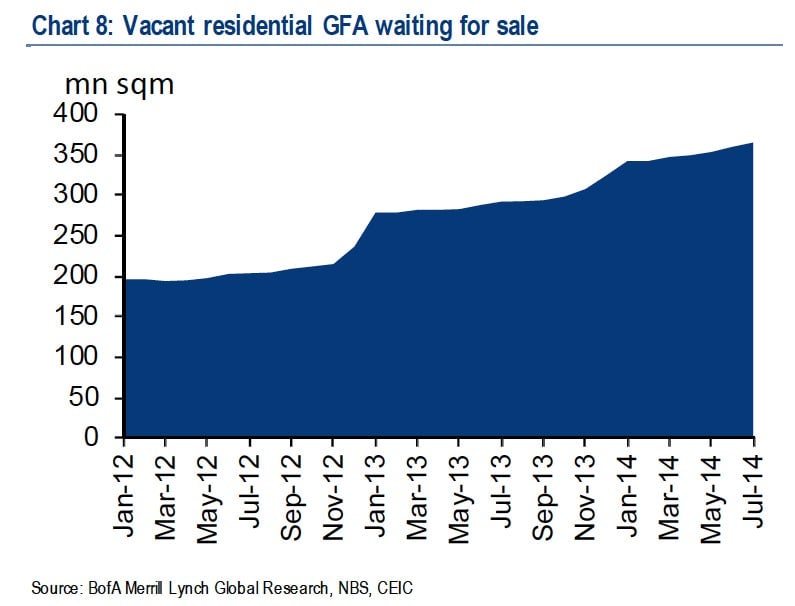

As of July, it would take about four months to sell off China’s housing inventory, assuming sales continued at the average volumes of the previous 12 months. That compares with 2.3 months in Dec. 2008, and 2.5 in Mar. 2012.

But current sales aren’t anywhere near the average pace of the 12 months. Dividing inventory by the six-month average makes things look even bleaker:

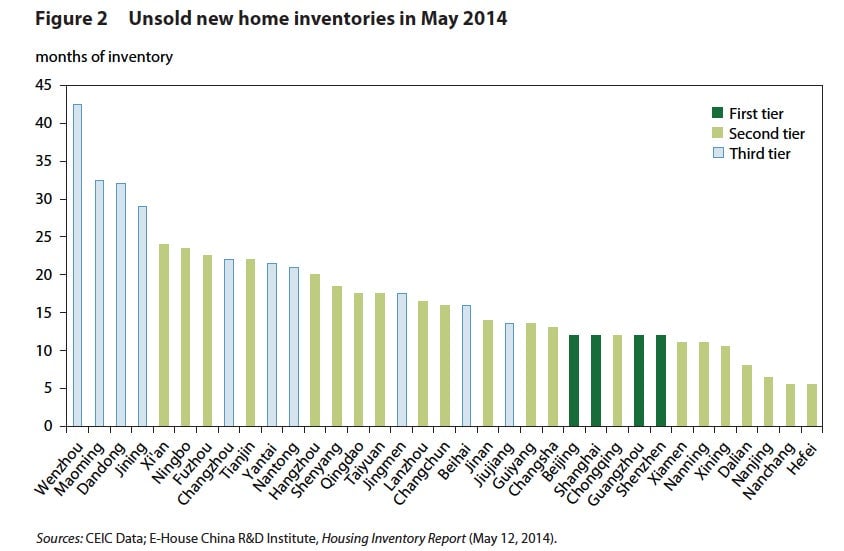

Will this unusually high inventory make this downturn worse than the last two? That depends on why people aren’t buying homes. Is it because the laws prevent them? Or because they don’t need them?

Liu says it’s the laws. Current rules bar households from buying more than two or three apartments. In both 2009 and 2012, relaxing those laws and loosening credit attracted buyers, halting those downturns. Reversing laws preventing migrants from buying homes in major cities, Liu adds, will see the next wave of Chinese urbanization buoy demand, as more rural folk move permanently to big cities.

But if home-purchase restrictions were the sticking point, prices wouldn’t have kept falling in the few-dozen cities that have already lifted them, says JLWC. The problem, they say, is that developers have built too many posh luxury apartments and not enough housing for middle-class families (let alone poor migrants).

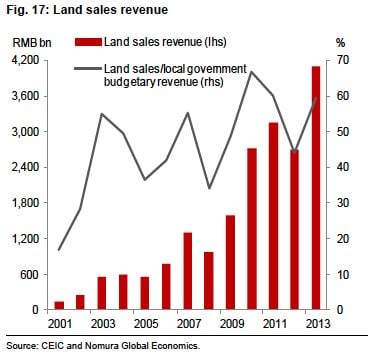

Since local governments depend on land sales for at least half of their budget, they sell to the top bidder—usually luxury developers, which can borrow cheaply and pass on land costs to rich customers. While China’s leaders have encouraged affordable housing construction, local governments consistently either failed to come up with the funds (paywall) or embezzled them.

Many worry that if China’s housing market crashes, so will its economy—a legitimate fear, given that around two-fifths of GDP comes from real estate. That doesn’t have to happen, says JLWC, provided the central government gets developers to build affordable housing. That glut of fancy housing, however, means a sharper drop in the housing market, is unavoidable, they say.