Another reason to fear a Chinese housing crash: 14% of China’s urban jobs are in real estate

There’s at least one thing in China that’s looking peachy right now: employment. Wages keep rising, and China has steadily more jobs than it has workers to fill.

There’s at least one thing in China that’s looking peachy right now: employment. Wages keep rising, and China has steadily more jobs than it has workers to fill.

But that could quickly change. Real-estate investment creates at least 14% of China’s urban jobs (pdf, p.14), says the IMF. As slumping property values drag down investment, tens—or maybe hundreds—of millions of Chinese workers could lose their jobs.

China’s big job engine

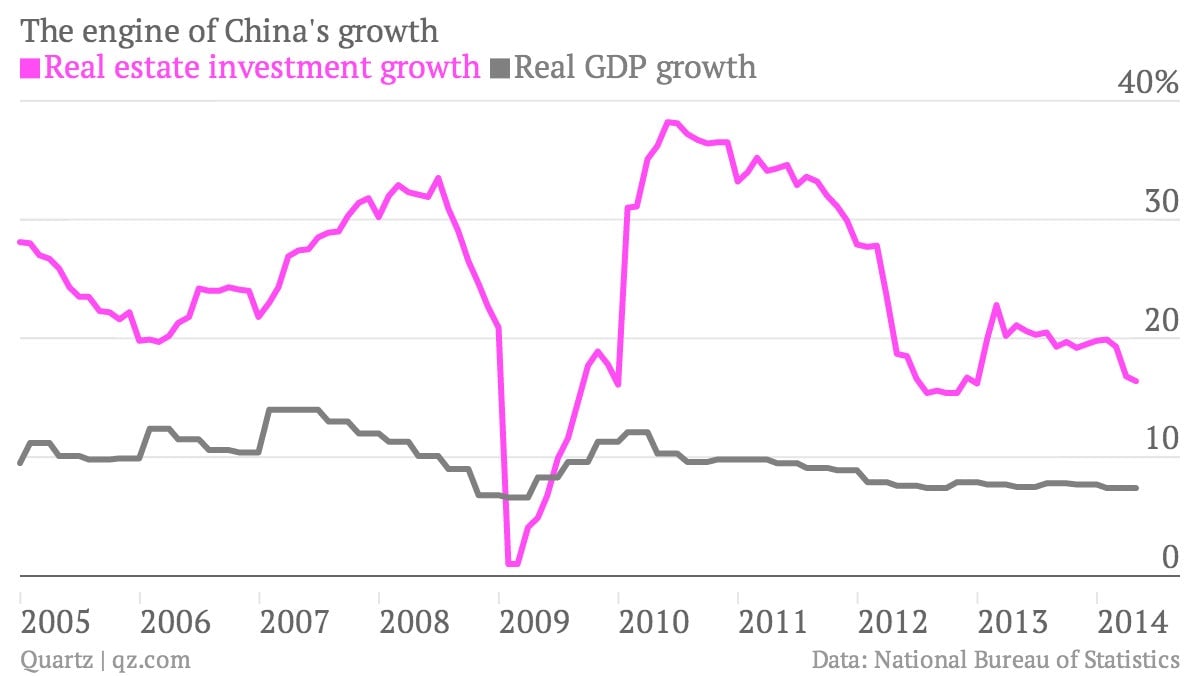

The beauty of any housing boom is that it needs lots of workers to build it. That employment fillip has served China’s leaders well. After the 2008 financial crisis threatened mass layoffs, they pushed banks to lend to property developers and infrastructure. It worked; by 2011, construction was creating more than half of new migrant worker jobs, according to Capital Economics.

That’s also part of why, even as China’s GDP growth slowed from 14.2% in 2007 to 7.5% last year, employment opportunities abound.

At least 14% of China’s urban workers…

But the curse of jobs so easily created is that they can be just as easily lost. With home sales falling in many Chinese cities, that may soon happen.

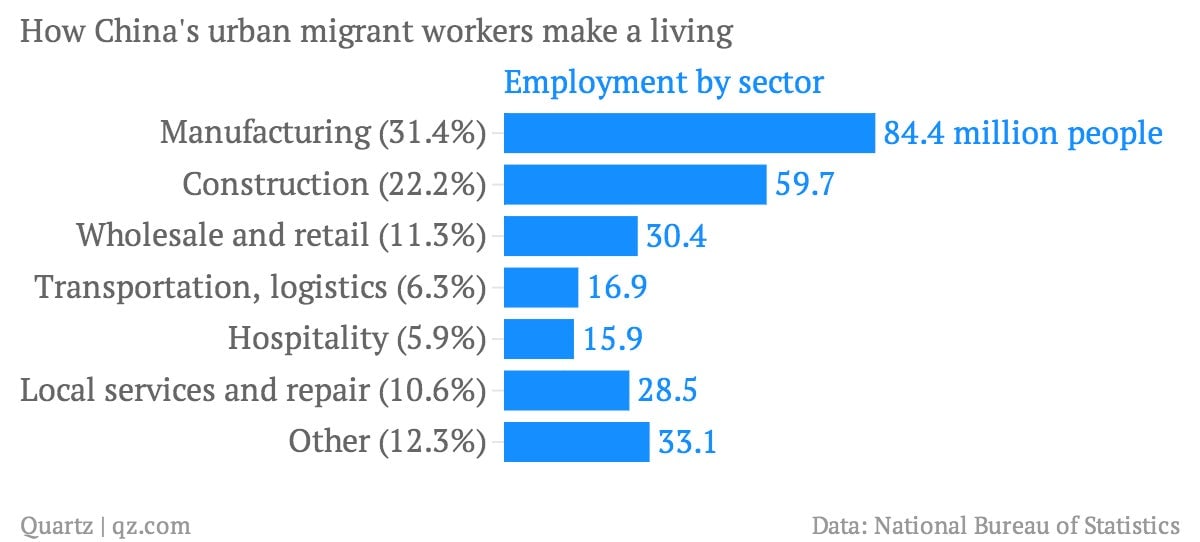

How many jobs are we talking? The IMF attributes 14% of “total urban employment,” which includes both residents and migrant workers, to real-estate investment. That’s roughly 90 million people.

But the IMF also calculates that property investment drives 12.5% of GDP. That’s seems a touch low considering Zhang Zhiwei, an economist at Nomura, puts it at 16%, while Société Générale’s Wei Yao argues the housing sector alone generates 20% of China’s output. If so, the IMF’s employment projection may have undershot too, which would mean tens of millions more jobs are likely at risk.

China’s most vulnerable workers

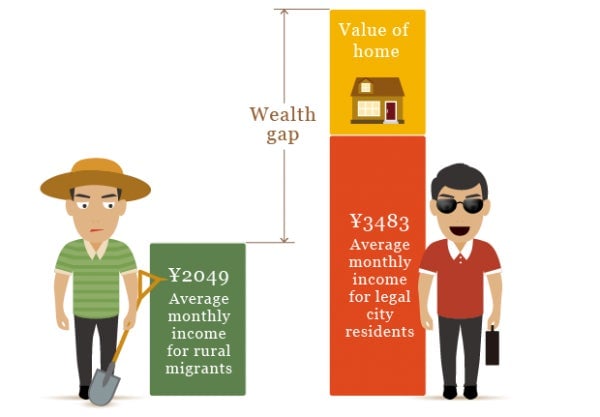

Beyond sheer numbers, another worry is that those hardest hit would be China’s least skilled, least educated workers, its 269 million-strong “rural migrants” (link in Chinese).

Though most migrants work in cities, under China’s household registration system, or hukou, their birth in the countryside classifies them as ”rural.” That bars most from receiving the superior social services that ”urban” residents get, such as health care or their children’s education, as ChinaFile explains.

They’re also simply much worse off. Last year, “rural migrant workers” earned an average of 11.7 yuan ($1.88) an hour (link in Chinese). Fewer than 1% owned their own homes.

Which is why it’s worrisome that these migrants depend heavily on construction for work:

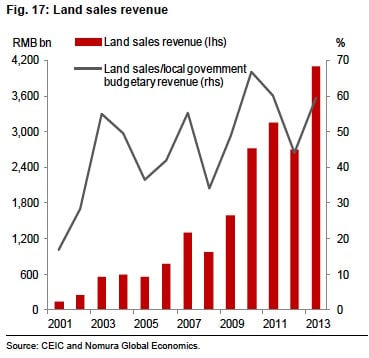

Construction jobs aren’t just in building luxury apartments; they’re also infrastructure gigs. But those too are closely tied to property. Local officials rely on land sales to fund employment-boosting infrastructure projects, an age-old ticket to Communist Party promotion.

Falling demand means they’re already struggling to sell new land parcels. If that continues, infrastructure funding will dry up.

Case study: the US housing crash

So how might things play out? At the US housing boom’s 2005 peak residential construction directly supported 5.1% (pdf, p.3) of total employment, or 7.4 million jobs. By 2008, that had withered by more than one-third:

Unfortunately for China, the US’s experience is probably the best-case scenario. Not only is China at least three times more reliant on real-estate investment for jobs, but the government long since exhausted stimulus measures that might help it dodge the effects of a US-style housing crash. China’s also just bigger. It might seem obvious, but 3 million frustrated jobless workers is nowhere near as scary as 30 million.