Property taxes could be the methadone for China’s debt addiction

Sick of the bad China news? Here’s a little silver lining for you. Officials in the National Development and Reform Commission, the body that’s responsible for drawing up urbanization plans, just proposed some measures that could help end China’s cycle of local government debt and cool its property market (link in Chinese).

Sick of the bad China news? Here’s a little silver lining for you. Officials in the National Development and Reform Commission, the body that’s responsible for drawing up urbanization plans, just proposed some measures that could help end China’s cycle of local government debt and cool its property market (link in Chinese).

In a report titled “Land System Reform and a New Kind of Urbanization,” NDRC officials proposed that land sales go to the central government, instead of to local governments as they currently do, and for local governments to levy property taxes instead. These measures could help align local government objectives toward “the sustainable development of the community,” says Patrick Chovanec, chief strategist at Silvercrest Asset Management and expert on China’s economy.

“Right now, local governments in China are dependent on land sales for a big chunk—some estimates put it at 40%—of their revenue,” Chovanec tells Quartz. “Local governments are essentially dependent on a continuing property boom…. It’s in their interests to boost property speculation.”

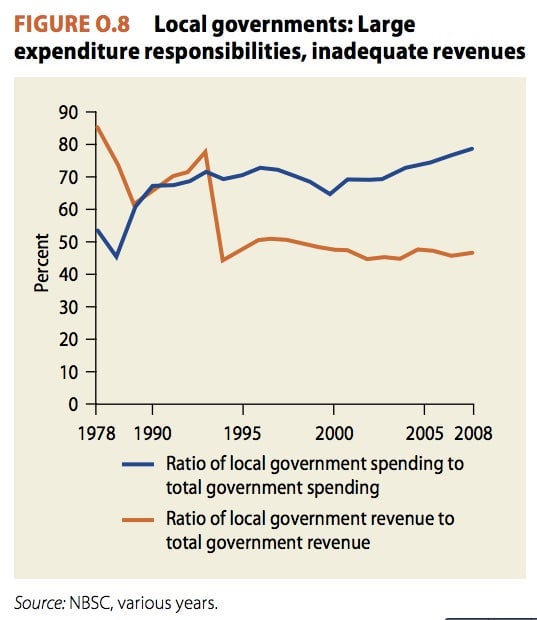

Here’s why that is. Local government officials are on the hook for posting big GDP growth numbers. They spend a lot more than the central government to achieve that—local governments are responsible for nearly 80% of total government spending though they receive 47% of revenues (pdf, p.7), as you can see in this chart from the World Bank (pdf, p.58):

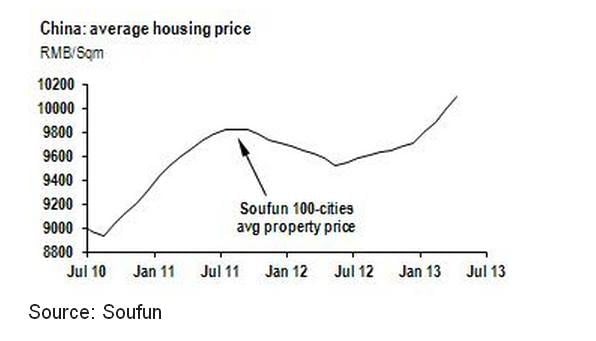

That’s left them unduly reliant on selling land parcels. This encourages local governments to do things like relocate local residents and seize their land, or sit on supply to drive up prices, which have soared in recent years (via beyondbrics):

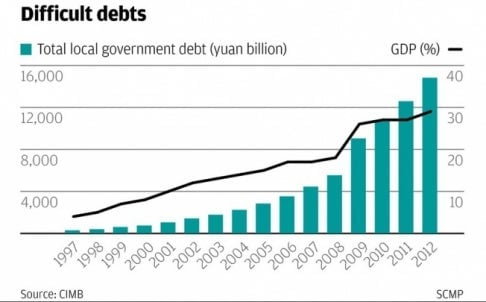

And even land-grabbing and speculation-encouraging hasn’t been enough to help fund the 2009-2011 stimulus, plunging local governments headlong into debt:

The result? Angry people evicted from their homes or stuck in rent purgatory. And local governments piling on debt to fund wasteful vanity projects.

The NDRC’s proposals would help in several ways. Directing sales of land parcels, to be sold at cost or a very slight premium, to the central government would help it create more affordable housing. Plus, a property tax would also discourage the buy-and-hold speculation among wealthy Chinese people, cooling prices.

Levying property taxes—at present, only Shanghai and Chongqing have a tax, and it’s nominal—would not only give local governments a regular income, it would also align their development incentives with the interests of their citizens, says Chovanec.

“What [local governments would] have to do is maintain or enhance property values,” he says. “So what this means is that you’re not just focused on the short-term gain from more construction. You’re focused on the long-term gain of the community.”

True, the government has mulled property taxes for a long time, and nothing has happened. But what’s new about NDRC’s proposal is that it addresses the deep flaws in the system that have so far made the measure unfeasible. Unlike much ballyhooed yuan internationalization or privatization of state-owned enterprises, these proposals are both effective and doable. And they’d encourage economic development of a sort that China’s never seen before—the sustainable kind.