Why are so many billionaires so eager to give money to institutions that clearly don’t need it?

Take billionaire hedge fund investor John Paulson. He’s famous mostly for his shrewdly structured bets against the US housing market, which paid off big when the US economy crashed hard in 2008 and 2009. Today he’s famous at Harvard University—he attended Harvard Business School—for having just written a $400 million check for an endowment at the Ivy League institution’s School of Engineering and Applied Science. That’s four times the amount he pledged to the Central Park Conservancy in 2012, and the largest gift Harvard has ever announced in the school’s nearly 400-year history. (Its previous record was the $350 million donation last year from the family of billionaire Hong Kong property investor Gerald Chan.)

The rise of mega-donations goes beyond Harvard Yard, even if it is the Crimson fundraising squad that’s the best in the business. Donors gave roughly $37.5 billion to US colleges and universities in 2014. Harvard alone brought in $1.16 billion.

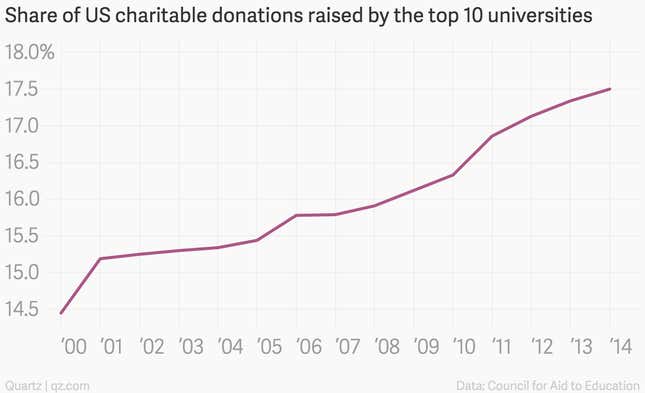

For what it’s worth, Harvard doesn’t really need the money. Its endowment stood at more than $36 billion as of June 2014, making it the largest such endowment in the country. And yet Harvard and other members of the university fundraising super-elite keep attracting a bigger and bigger share of the largesse earmarked for higher education. In 2000, the 10 universities most successful at fundraising captured roughly 14.5% of all voluntary donations made to US institutions of higher education. Today their share is up to 17.5%.

There are all sorts of reasons why people make donations. It can make them happy, for one thing, generating the “warm glow” linked to helping a good cause, as described by economist James Andreoni in the late 1980s. High-profile donations can be a great way to signal status. Oh, and in the US there are giant tax benefits tied to such donations, at both the federal and state level.

But as monster endowments continue to grow, policymakers need to reconsider whether this makes any sense.

Some tax exemptions for charitable giving are probably a good thing. But unlike private foundations, under US law doesn’t require public charities—a group that includes churches as well as colleges and universities—to meet a minimum payout ratio in order to qualify for tax exemptions. The argument has been made, including by Harvard Law School’s own Daniel Halperin, that this tax treatment could actually play a role in incentivizing the accumulation of large endowments. The thing is, this is not a desirable outcome.

The reason the government gives tax exemptions is that it wants the money raised to be spent on a public good, not stockpiled in a massive piggy bank where the money mainly is steered into investments specifically intended to help the fundraising institution earn even more money. If the money isn’t being spent any time soon, why should taxpayers continue to subsidize these donations?

Finding a solution to this problem would be tricky. Requiring a minimum level of payouts, for example, would be too blunt an instrument, limiting the flexibility endowments need to manage in bad years for investment returns. But it finally might be time to at least consider a tax on “excess endowments,” as some experts have suggested.