The Shanghai Composite Index fell 1.3% on July 7, days after the Chinese government vowed to prop the benchmark index up. It has a lot farther to fall, says Victor Shih, professor at University of California, San Diego.

“[E]ven with a government rescue, it could be quite some time before the backlog of existing sell orders are cleared,” Shih tells Quartz. “This will continue to out downward pressure on the market.”

The markets’ fall has a lot to do with the murky world of Chinese margin trading, which skyrocketed in 2014:

In general, margin finance allows investors to borrow from brokerages to boost their stock bets, usually using the underlying shares they purchase with these loans as a deposit. This magnifies gains and losses. If the stock goes up, the investor pockets the additional profit, minus commission to his broker, after he sells But if the stock drops, he has to pay back the borrowed cash and swallow his losses.

When stocks drop enough that brokerages get twitchy about ever being able to get their loans back, they demand that their clients pony up more money or stocks as a deposit. If these “margin calls” force enough liquidation at the same time, it can create a cascade of falling share prices, that in turn spark more margin calls.

In China’s case, a lot of that margin finance flowed into the most speculative part of the market, super-volatile small-cap stocks, says UCSD’s Shih—the stocks that have been tanking the hardest.

China tries to prevent margin call disasters with a rule suspending a stock from trading for a day once it’s lost 10%. But that does not actually solve the problem—it just stalls it.

“When the stocks began to sell off, margin calls rolled in,” says Shih. “However, because of the rule… margin lenders could not liquidate positions in many cases.” Even though not all the positions have been sold out, stocks are down to practically where they were before the recent several-month bubble.

Proceeds from wealth management products sold by banks to retail customers have been a major source of funds loaned out for margin trading, says Shih.

Even dodgier fund sources—things like “umbrella trusts” and share-collateralized bank borrowing—also abound, allowing investors to leverage themselves as much as ten times, says David Cui, strategist at Bank of America Merrill Lynch.

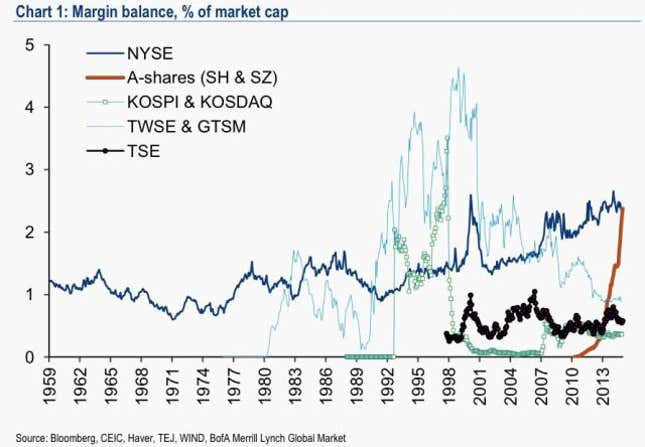

The latest official data put margin balances at around 2 trillion yuan ($320 billion). However, those data don’t count the huge portion of the trade funded outside official channels. In early June, Cui estimated margin finance could total as much as 6 trillion yuan—equivalent to nearly 10% of China’s GDP. This chart should give you a sense of how China’s margin balance stacks up against other major markets (although bear in mind it’s from December 2014, back when official margin balances were half what they totaled in early June).

It’s unclear how much of that has been unwound. Citigroup estimates that only one-fourth of these margin positions have been forced out so far, reports FT Alphaville (registration required). If Citigroup and Cui’s estimates are correct, that means there’s potentially 4.5 trillion yuan (in borrowed funds still tied up in China’s markets.

One nagging question in all this is: why would banks’ wealth management product customers allow their precious savings to be lent out to stock gamblers in the first place? Probably because of what’s called China’s “implicit guarantee” that the government will one way or another cover any losses.

This is in part because many banks are state-owned, though also because the government hasn’t yet allowed any WMPs to fail. That means that as margin trades start unwinding, the government could have much more than a collapsing market on its hands. It will also have to decide who swallows the losses.