The shadowy trading behind China’s stock market boom

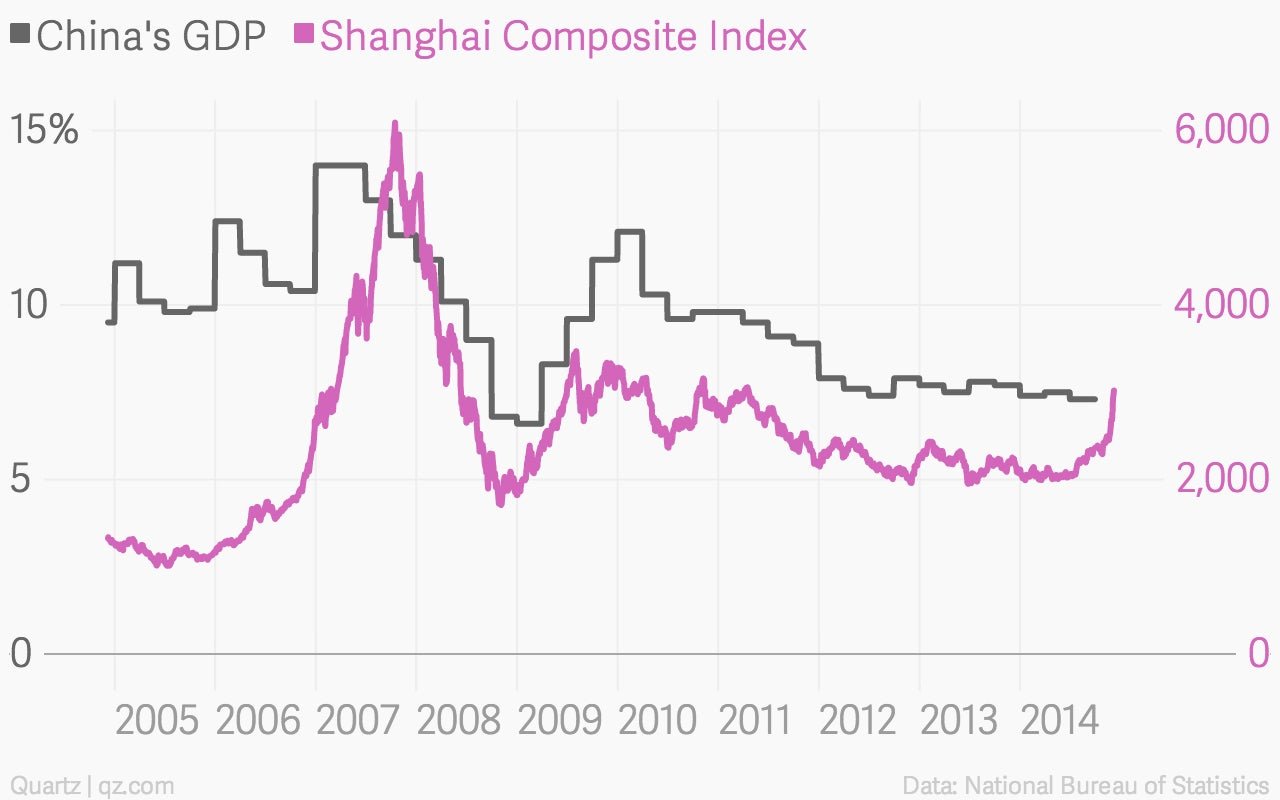

The madness is official. Earlier today, China reported trade data showing not only faltering export demand but eroding domestic consumption as well. And yet, the Shanghai Composite Index leapt 2.8% today.

The madness is official. Earlier today, China reported trade data showing not only faltering export demand but eroding domestic consumption as well. And yet, the Shanghai Composite Index leapt 2.8% today.

That puts it up 45% since the beginning of 2014. The last time China had a mega-rally was in 2007, when the Shanghai Composite nearly breached 6,100 (it’s at 3,020 today). But while the momentum might feel the same, there’s one enormous difference: leverage—and lots of it.

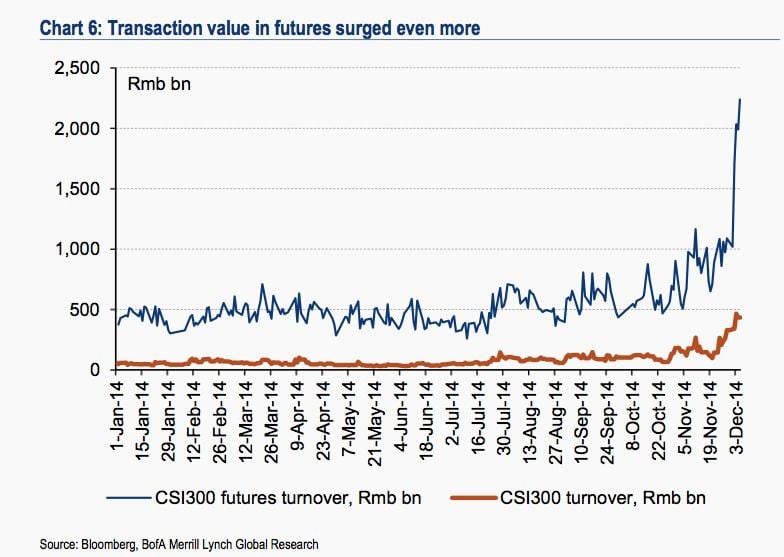

“Once the market began rising, leverage soared,” says Chen Long, an economist at GaveKal, in a note. Chen notes that the outstanding value of margin positions in mainland markets is now 800 billion yuan ($129 billion)—twice what it was July. The daily turnover of the CSI 300 index futures just topped 2 trillion, a fourfold increase in the space of a week.

This mania for margin trading—which allows individual investors to borrow from the broker to up the amount of their stock bets, magnifying the size of gains and losses—is a new thing. Back in 2007, Chinese stock regulators forbade leverage. But as part of an effort to open up financial markets, they’ve softened restrictions of late. In October, nearly 5 million retail investors had margin accounts, up from less than a million two years prior.

Yet another big difference: Shadow finance, which barely existed in 2007, is now creeping into China’s stock market, says Bank of America/Merrill Lynch’s David Cui.

In theory, banks aren’t allowed to finance stock purchases. But to profit from the bull run in mainland-listed shares (known as A-shares), they’re selling their customers wealth management products (more on those shadowy instruments here), putting those funds in trusts that then lend them on to stock investors. Trusts will give investors amounts worth three times their position, or more—much more than brokers tend to lend. Margin rates average about 9% a year; banks issue WMPs at a tidy profit of about 4-5%. As for futures trading, leverage of 10 times the position is “quite normal,” says Cui.

But if leverage has been around for two years now, why are mainland-listed shares only now rallying? Because the Chinese government has been drumming up enthusiasm for stocks, including in its surprise launch of the Shanghai-Hong Kong Stock Connect—which, so far, has boosted A-shares minimally. It has also encouraged investment in its state-run press.

“The government may be hoping, by engineering a buoyant stock market through words and deeds, companies can raise equity (rather than debt) so the whole economy can de-leverage,” writes Cui, adding that a stock boom also should boost consumption by making people feel richer.

He’s skeptical that will work, though.

China’s Q3 GDP grew at a five-year low of 7.3%. This quarter isn’t looking better. “Pretty much all growth drivers in China appear to be sputtering,” wrote Cui in a note today, including US dollar strength’s pressure on exports, sluggish domestic consumption, rampant excess capacity, and a still-darkening housing market.

The dicey thing with leverage, notes GaveKal’s Chen, is that when the market finally reverses, it’s abrupt and steep. That might happen because brokers run out of money to lend, or because slowing growth causes loan defaults. “When the tide recedes, the backwash is likely to be vicious,” he says.