This has been a big week in Chinese financial history: It marked the first time people outside mainland China could buy Shanghai-listed stocks. This was thanks to the Shanghai-Hong Kong Stock Connect, often called the “through train,” which also allowed individual mainland Chinese investors to buy the big-name companies listed in Hong Kong—Tencent, for example, or Prada.

China’s zipped-up capital account meant that, before this week, these purchases could only be made by institutional investors.

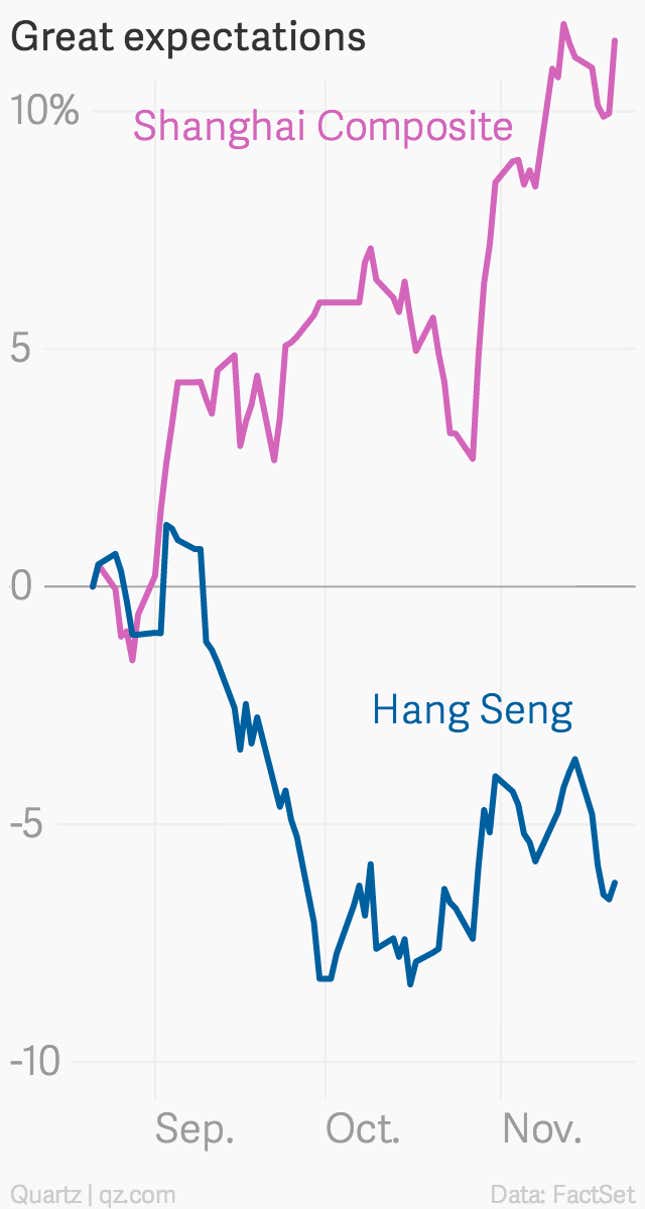

This was to be “one of the most significant openings of China’s capital accounts in a decade,” said the Financial Times (paywall), and a big step in “internationalization” of the yuan (paywall). Both Hong Kong and Shanghai shares shot up after the program was announced.

Despite the hype, though, the Shanghai Composite index ended the week up just 0.3%, while Hong Kong’s Hang Seng slipped 2.7%.

What happened?

“Early days, so hard to extrapolate, but it doesn’t look promising,” says Kevin Yeoh, an analyst at J-Capital Research, a Beijing-based research firm. “Looks like the Shanghai market had rallied in anticipation and those who had already bought [then] sold to the new Northbound investors when Connect started.”

And mainland investors didn’t invest in Hong Kong, evidently.

Though it’s way too early to declare the program a dud, the problems in the first week hint at larger struggles China faces as it opens up its capital account.

“Stir-fried stocks”

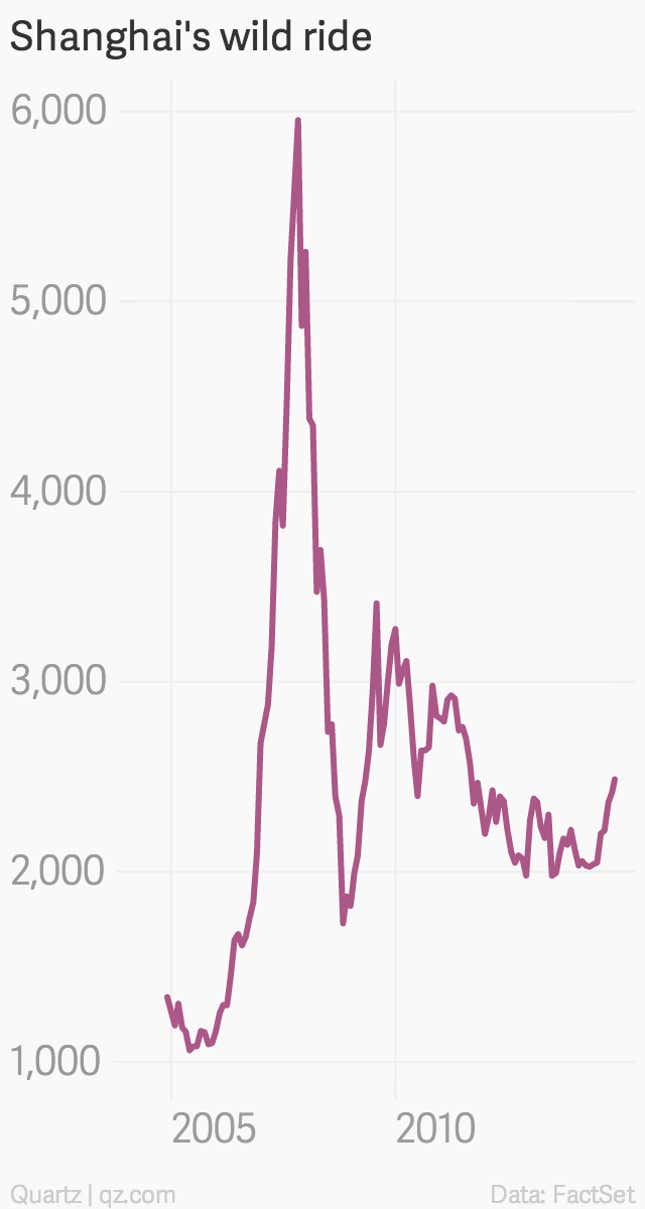

There’s a term for the cynical bet made by mainland investors: “stir-frying stocks.” One of the Stock Connect’s objectives is making Chinaese markets operate less like casinos. Insider trading abounds, and with four-fifths of investment coming from retail investors, volatility roils the market.

This reflects the same speculation that has inflated a dangerous housing bubble, which is now starting to burst. As it happens, some think the reason the government suddenly okayed the Connect now, after five years of mulling over it, is because nosediving housing prices mean Chinese households need something else to hold their investments in.

Of course, China could instead crank open its capital account and let those people invest in whatever market they want. But that likely means capital will flood out, which would devastate the economy.

The little guy gets screwed—again

As David Cui, strategist at Bank of America/Merrill Lynch pointed out in a recent note, onshore investors who wanted to invest in Hong Kong stocks have probably already gotten their money out via unofficial channels. Moreover, to buy Hong Kong stocks via the Connect, mainlanders must invest a minimum of 500,000 yuan ($81,600)—a pretty high threshold for most Chinese households (the country’s per capita disposable income is 18,311 yuan a year).

Those with that kind of money are much likelier to have availed themselves of those unofficial channels. Meanwhile, middle-class households have to content themselves with a sinking housing market, or wildly swinging mainland stocks, to hold their wealth.

Building transparency

One of the Connect’s aims is to attract foreign institutional investors, limiting volatility. But so far, those that have been allowed to invest in A-shares—as mainland stocks are called—through the QFII (qualified foreign institutional investor) program, have invested in three or four big-name, reputable companies—Ping An Insurance or Saic Motor, for example—and ignored the index, says J-Cap’s Yeoh, “to avoid battling all those crazy forces in the market.”

“In an A-share rally, you get totally smashed because Lao Wang [the Chinese equivalent of Joe Schmoe] is buying Rubbish.com and you have a massive junk rally and you’re holding large-cap stocks,” he says. “But in a bear market, you outperform completely.”

And China’s been in a bear market for nearly seven years now.

Creating a more stable market means improving the quality of listed companies. But the regulator asks little of listed companies in terms of corporate governance or transparency. And with the economy slowing rapidly, companies aren’t likely to suddenly get less shady.

Liquidity, liquidity, liquidity

By sucking new investment into Shanghai-listed stocks, the Connect was supposed to lower borrowing costs for mainland companies. As the Wall Street Journal flags, the arrangement was rigged to benefit Shanghai more than Hong Kong (paywall). The plan limits northbound investment to 13 billion yuan ($2.1 billion) a day, capped at 300 billion yuan a year, and 10.5 billion yuan a day for southbound flows, with a 250 billion yuan annual ceiling.

But the Connect is not a very big opening in the capital account: that 300 billion yuan is just 2.5% of mainland bank deposits. But it’s nearly three times what China brought in last year in FDI.

And China is addicted to new influxes of money. Its trade surplus and foreign investment are shrinking fast, and, as we’ve discussed, that pinches Chinese companies, which need steady inflows of cash to keep from drowning in debt. The Connect could be a coveted new stream of liquidity.

Confidence games

The Connect is also symbol of confidence in China’s future, which is why its success is so important to the Chinese leadership. In this and all those other ways, the Stock Connect is a microcosm of China’s larger economic challenges.

The government says it wants to let markets, and not political priorities, determine the value of capital and investments. The barely discernible follow-through on promised reforms, however, suggests squeamishness at accepting that the market and the Communist Party often disagree. The Connect is at least a tiny experiment in forcing the Chinese government to swallow that sometimes unpalatable reality.