This item has been corrected.

The NASA mission exploring the Kuiper Belt—the remote corner of the solar system hosting, amongst others, Pluto and its moons—has beamed home an image of the dwarf planet taken at the closest range yet, about 7,750 miles from the surface of Pluto (or, as NASA itself said, from a distance similar that between Mumbai and New York City). A spacecraft known as New Horizons traveled for more than nine years and 3 billion miles to get the shot. This is the farthest out humankind has reached in the Solar System; it is spellbinding.

Many of the people who saw the picture, including those romantics at NASA, noticed that the area in the lower part of the frame resembles a heart. The social media-savvy space agency replied to the “love letter” from Pluto, on behalf of the universe, in its Twitter cover image.

Following NASA’s tradition of sending items from home into outer space, the New Horizons spacecraft carries a compact disc containing the names of 430,000 people who, in September 2005, answered NASA’s call to support the mission and signed up to have their names sent to the solar system’s ninth and furthest planet.

Sure enough, when New Horizons left planet Earth on January 18, 2006, Pluto still enjoyed the status of planet. But it wasn’t always called Pluto. And wouldn’t stay classified as a planet for long.

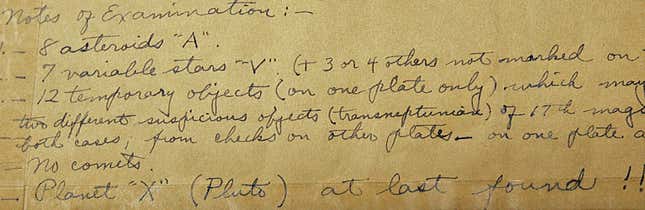

The search for “Planet X,” as it was originally called (it was later renamed Pluto at the suggestion of an 11-year-old girl with a passion for Greek mythology), had been ongoing since the early 1900s. Faint traces of what can be now recognized as Pluto appeared in several images from 1909 to 1915. But the official discovery of the planet Pluto wouldn’t be announced until 1930, by a 24-year-old American astronomer named Clyde Tombaugh (pdf). He died in 1997; a portion of his ashes were placed onboard New Horizons for its trip to Pluto.

Pluto was initially believed to have a mass similar to the Earth’s—arguing for its planethood—but subsequent studies revised it to a tiny fraction of that, from 0.1, 0.01, 0.002, and finally 0.00218 the size of the Earth. The downsizing carried with it doubts as to whether the celestial body was or was not an actual planet. On Sept. 13, 2006, a few months after the New Horizons mission started, Pluto was downgraded to a dwarf planet.

This was the result of an International Astronomical Union (IAU) resolution about the definition of a planet. It was decided that, to be considered such, a planet had to:

- Rotate around the sun;

- Have sufficient body mass that its gravity turned it into a round(ish) shape;

- Have cleared the area around its orbit.

Pluto fails to fulfill the last requirements (in addition to the reduced body-mass estimate, at least two large objects were found in its orbit), and hence, the IAU declared there to be only eight planets in our solar system: Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune.

The resolution was approved by 424 astronomers and delivered to the press by Mike Brown, the Caltech researcher who had discovered Eris, a dwarf planet in Pluto’s orbit with a bigger mass than Pluto itself. The announcement has since gained the astronomer the nickname (and Twitter handle) of “Pluto Killer.”

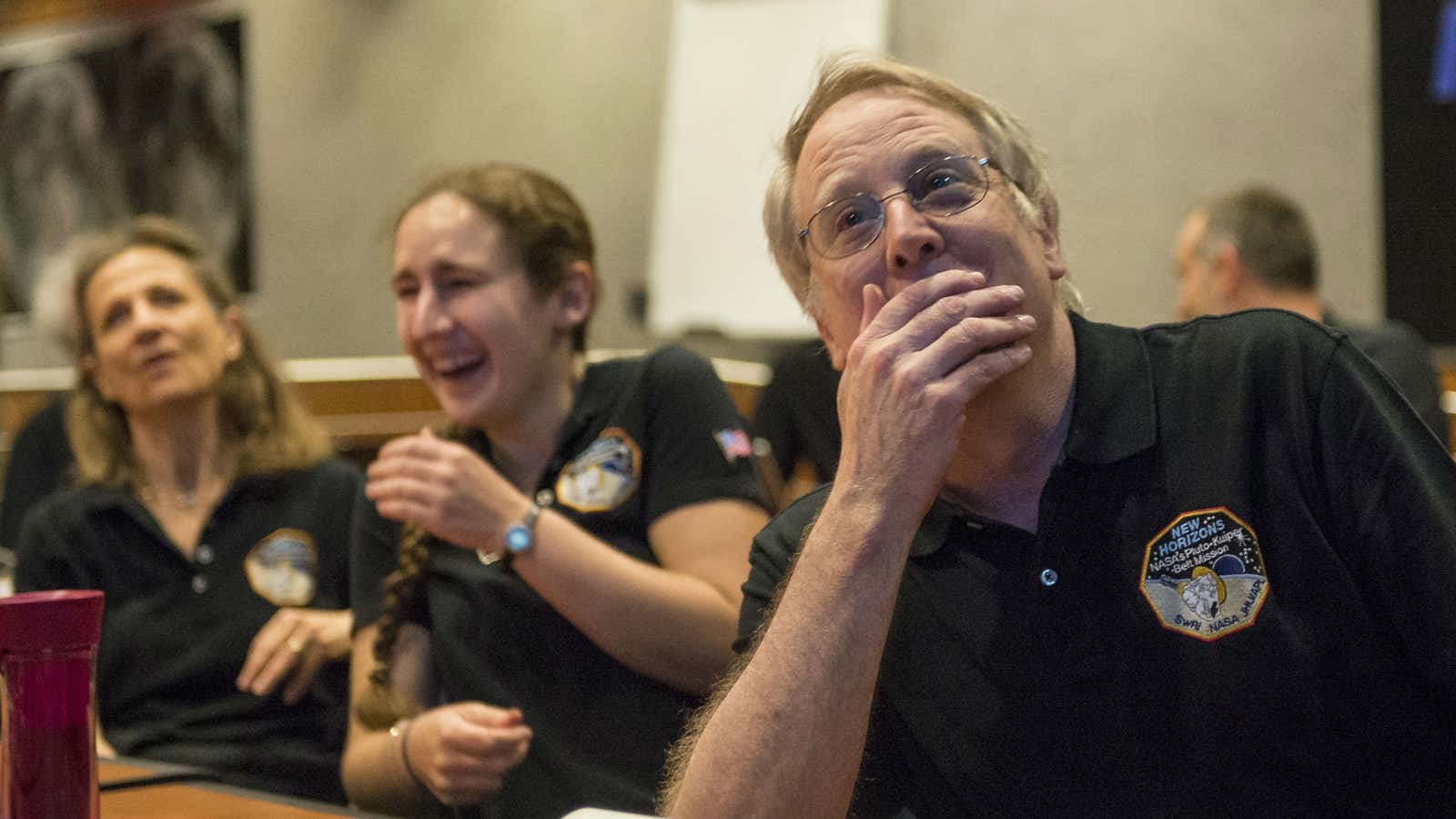

Not everyone was as humored by the decision.

Alan Stern, the head of the New Horizons mission, declared at the time: ”I’m embarrassed for astronomy.” He called the decision a “farce,” arguing that the definition wasn’t accurate and that the area around the orbit of other planets is also not cleared. A petition to overturn the decision was presented, but with no success—although the state of New Mexico legislated legislated that, ”as Pluto passes overhead through New Mexico’s excellent night skies, it be declared a planet.” The Illinois Senate passed a similar resolution, and the California State Assembly referred to the downgrading of Pluto as “a heresy.”

The clamor around Pluto’s status was such that in 2006, the American Dialect Society declared “plutoed,” meaning “demoted or devalued,” the word of the year.

There is still no complete agreement to this day, despite the official IAU position. In 2008, NASA sponsored a conference called “The Great Planet Debate.” The intention was to find consensus on the definition of planet, and hence on whether Pluto fits into it. The participants did not find an accord, settling instead on the definition of Pluto and similar planets as “plutoids.”

But although the defenders of Pluto’s honor might be unhappy that even a heart-shaped surface doesn’t warrant readmission to the planet club, the fact that it was found on a body with the status of dwarf planet does not make today’s achievement any less impressive.

As Neil deGrasse Tyson explains in this video, “It’s not everyday that we get to see something for the first time.” And thanks to the web, we get to witness this discovery vicariously as if it were our own.

Correction: Voyager, not New Horizons, reached the furthest out in the universe.