A tempting box for a sugary cereal designed to bait kids. Hip sneakers produced in sweatshops. Convincingly forged diplomas and documents. The 3D-printed gun.

Sure, designers can be co-creators of life-enhancing projects—but they are also often accomplices in creating evil inventions and products with pernicious consequences.

Realizing the potency of their creative output, a group of designers have banded together to craft their own version of an ethical code, like medical practitioners’, with the widespread principle to ”first, do no harm.”

Initiated by Samantha Dempsey and Ciara Taylor from the New Hampshire-based design agency Mad*Pow, the so-called “Designer’s Hippocratic Oath” is an attempt to reassert an ethical dimension into the design decision process, similar to the ancient code of conduct for doctors named after Hippocrates, the father of Western medicine.

“Designers are responsible for creating more than ever before—not only designing services, but also experiences, environments, products and systems for millions of people,” Dempsey and Taylor explain. “With this increased influence, we must take a step back and recognize the responsibility we have to those we design for.”

Dempsey and Taylor both work in the field of experience design, a specialization focused on enhancing a user’s ease or engagement with a designed product or experience. In particular, the two have been working on projects for the healthcare industry.

Call to conscience

The “Designer’s Hippocratic Oath” is certainly not the first time designers have had a call to conscience. For several design specializations, there have been similar attempts at a customized code. A 10-point pledge was proposed by product designer Laura Javier, who now works for Facebook. There is even a unique Hippocratic Oath for landscape architects.

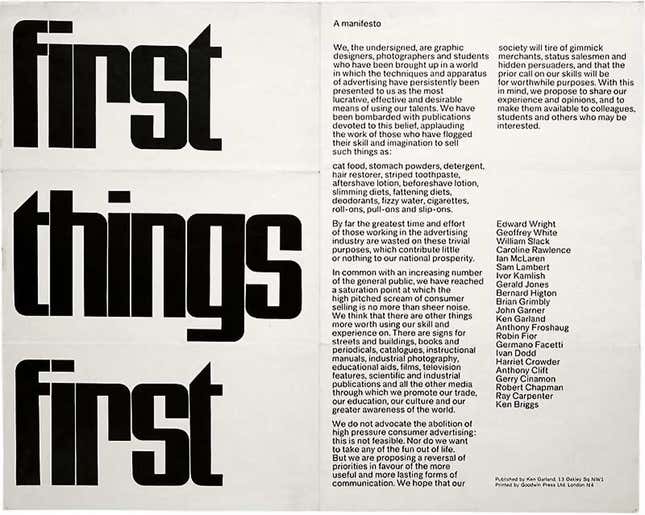

For graphic designers, the British designer Ken Garland initiated the First Things First manifesto in 1964, a polemical corrective to the overly commercialized climate of the design industry in the UK during that time.

In 2000, First Things First was resurrected, with renewed zeal from an international cadre of designers and writers including Eye magazine founder Rick Poynor, German typographer Erik Spiekermann, Dutch book designer Irma Boom, and legendary graphic designer Tibor Kalman. Echoing the sentiment of its predecessor, First Things First 2000 stated:

“Designers then apply their skill and imagination to sell dog biscuits, designer coffee, diamonds, detergents, hair gel, cigarettes, credit cards, sneakers, butt toners, light beer and heavy-duty recreational vehicles… Many of us have grown increasingly uncomfortable with this view of design. Designers who devote their efforts primarily to advertising, marketing and brand development are supporting, and implicitly endorsing, a mental environment so saturated with commercial messages that it is changing the very way citizen-consumers speak, think, feel, respond and interact. To some extent we are all helping draft a reductive and immeasurably harmful code of public discourse.”

In their own words

In Dempsey and Taylor’s “Designer’s Hippocratic Oath,” however, instead of a standardized manifesto to swear by, designers declare their commitment in their own words.

“Like those before us, we are calling on our fellow designers to consider our role and the ethics behind the work we do,” Dempsey tells Quartz. “But unlike these existing manifestos, pledges and projects, we are asking the design community to collaboratively create its own oath, instead of relying on an individual or a sub-set of designers to write one for us.”

So far, the duo have recruited only a small group of designers, mostly working in the field of experience design, to write their own pledges, but they’re hopeful that the initiative will take off with new participants, advocates, and backers.

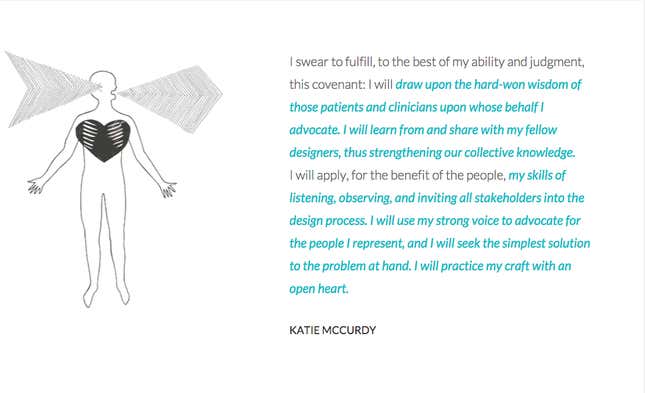

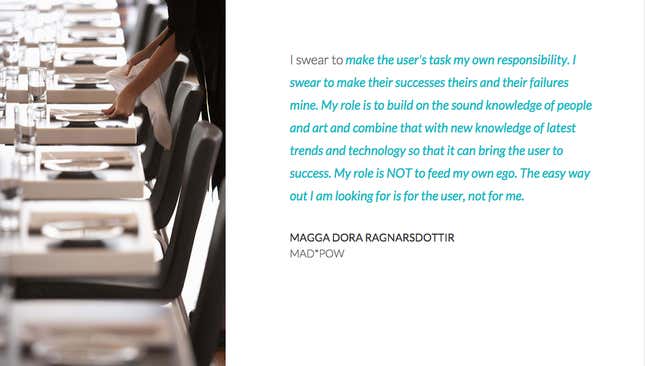

Accompanied by custom-made illustrations, here are some examples of the personal oaths they have gathered:

Ethics as trend?

The insistence on a unique oath is Dempsey and Taylor’s attempt to make the words actually stick. While the various initiatives, like two versions of First Things First, have gained considerable publicity, the matter of ethics in the design industry has remained largely a matter for pie-in-the-sky philosophical discourse. The fervor about the ethical dimension of design seems to rage and fizzle like any other trend.

Milton Glaser, one of the most thoughtful voices in the matter and a signatory of the First Things First 2000 manifesto, explained the conundrum for designers who usually work on commission for commercial clients.

“I had complaints about the First Things First Manifesto,” Glaser has said in an interview. “It didn’t give people any place to go. It suggested that one could get out of the business or work for nonprofits. It lacked reality. Once you accept the idea that we are living in a capitalistic enterprise, and that there is a potential for good in capitalism, you have to give people some leeway. You can’t simply say, stop working and supporting your family.”

To demonstrate his point, Glaser drafted the Road to Hell, a kind of soul-searching questionnaire inspired by Dante’s dark journey to Inferno. Glaser asked designers:

Would you—

Design a package to look larger on the shelf?

Do an ad for a slow-moving, boring film to make it seem like a lighthearted comedy?

Design a crest for a new vineyard to suggest that it’s been in business for a long time?

Design a jacket for a book whose sexual content you find personally repellent?

Design an advertising campaign for a company with a history of known discrimination in minority hiring?

Design a package for a cereal aimed at children, which has low nutritional value and high sugar content?

Design a line of T-shirts for a manufacturer who employs child labor?

Design a promotion for a diet product that you know doesn’t work?

Design an ad for a political candidate whose policies you believe would be harmful to the general public?

Design a brochure piece for an SUV that turned over more frequently than average in emergency conditions and caused the death of 150 people?

Design an ad for a product whose continued use might cause the user’s death?

When aesthetics substitute for ethics

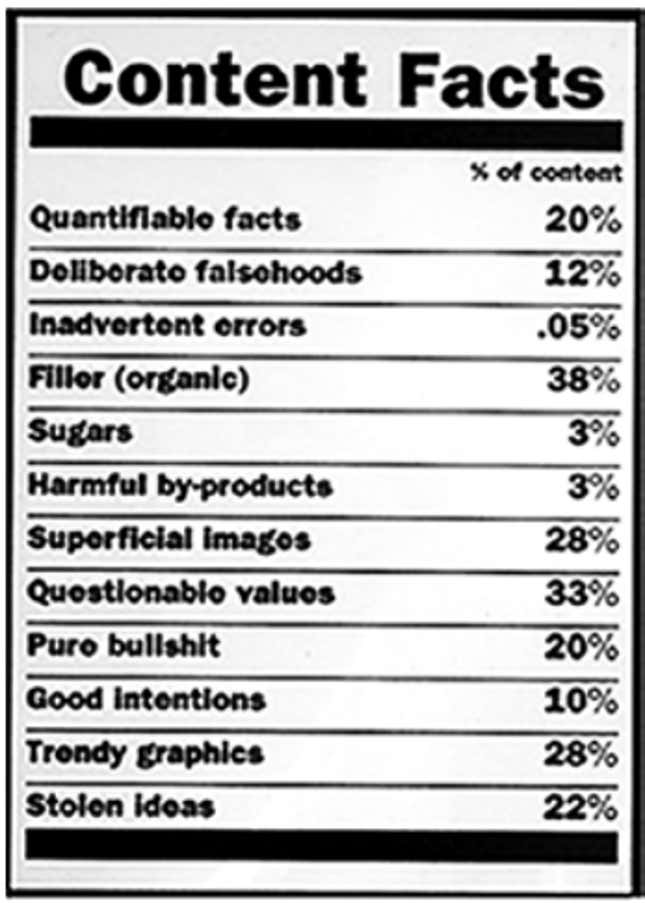

Perhaps part of the problem when it comes to instituting an ethical code for designers is these earnest statements of moral boundaries often themselves become design projects—as the many overly designed versions of the once raw and charged words of the First Things First manifesto show. The act of making a snazzy poster or clever illustrations to convey a set of ethical guidelines ends up becoming the project, rather than actually implementing and living by those guidelines.

Hopefully one day soon, especially as design’s domain becomes even more all-encompassing, designers will realize that when it comes to ethics, the real project is less about presentation, and more about practice.