The next design trend is one that eliminates all choices

In 2004, psychologist Barry Schwartz wrote The Paradox of Choice, a compelling manifesto that outlined the paralysis and dissatisfaction one feels when presented with too many choices. A decade later, Aaron Shapiro, the CEO of the global digital design agency Huge, has evolved Schwartz’s observations into a provocative scenario he calls “anticipatory design.”

In 2004, psychologist Barry Schwartz wrote The Paradox of Choice, a compelling manifesto that outlined the paralysis and dissatisfaction one feels when presented with too many choices. A decade later, Aaron Shapiro, the CEO of the global digital design agency Huge, has evolved Schwartz’s observations into a provocative scenario he calls “anticipatory design.”

In Shapiro’s vision, not only are there a limited number of choices, but there are none. With 12 offices worldwide from Brooklyn to Bogota, Shapiro oversees one of the most influential creative agencies in the world, providing branding, integrated marketing, and digital strategy services for multinational clients such as Nike, Lexus, Google, Pepsi, and Pfizer.

“Choice is overrated,” he opined. In his treatise about the agency’s newly-defined design approach, he wrote:

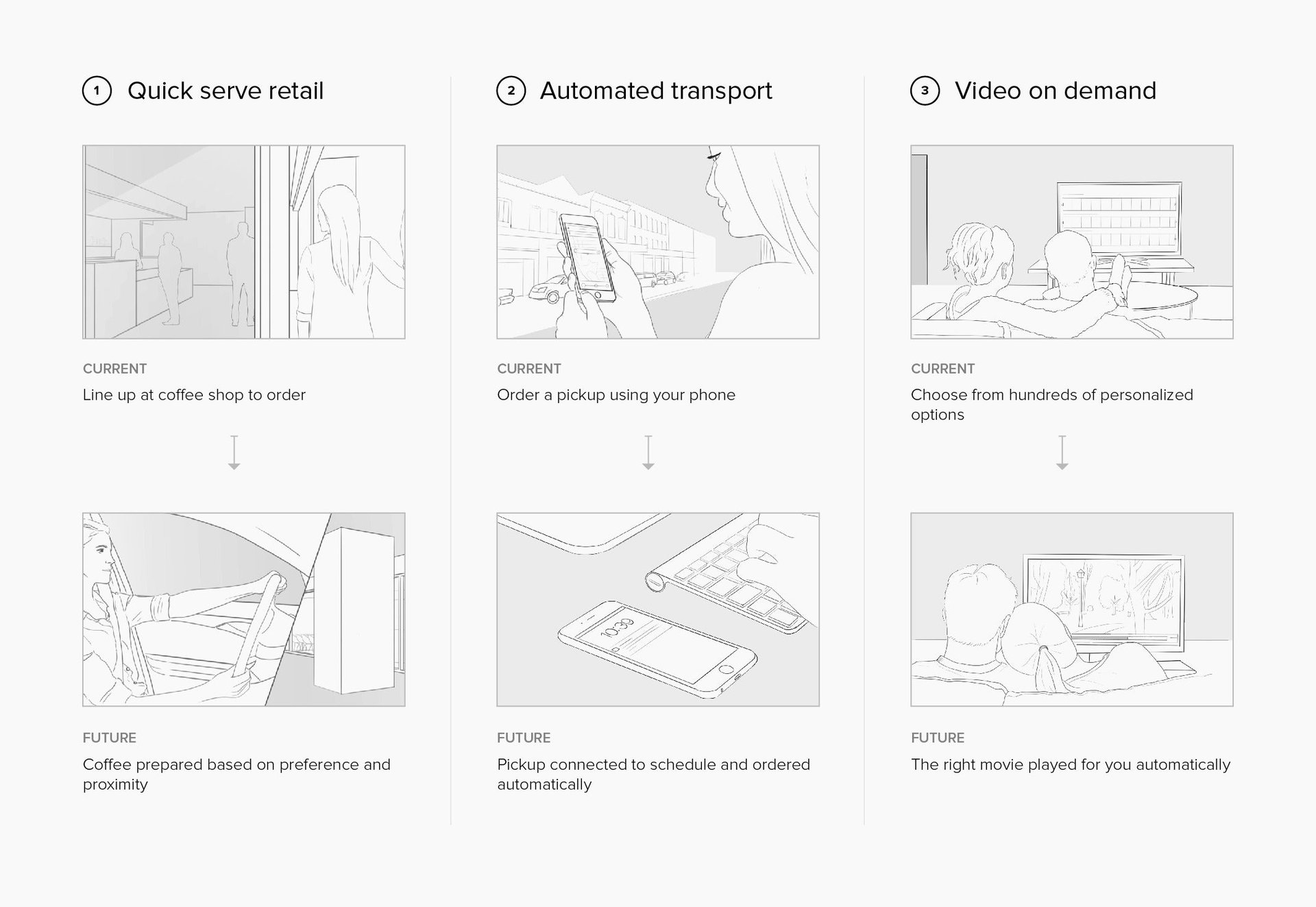

The next big breakthrough in design and technology will be the creation of products, services, and experiences that eliminate the needless choices from our lives and make ones on our behalf, freeing us up for the ones we really care about: Anticipatory design.

A radical mindshift

Despite its rather old-fashioned name, anticipatory design (not to be confused with Buckminster Fuller’s anticipatory design science) is actually a radical shift in terms of thinking about design. Up to now, the tendency of designers has been to provide customers with as many options as possible—various colors for vacuum cleaners, feature options for calling plans, and a spectrum of detergents for any kind of stain or proclivity.

Anticipatory design eliminates all that and presents a singular option. “Flow not friction,” “convenience not choice,” and “efficiency not freedom” are the mantras of anticipatory design.

The ultimate aspiration is to liberate us from so-called ”decision fatigue,” like the tedium of calling a taxi after a late meeting to get to a concert, for example. With anticipatory design, not only will the car be waiting for you but the driver (if any) will know your destination and the optimal route to take to get you there on time.

Anticipatory design gets at something that Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg mentioned when he was asked why he wears essentially same uniform-like outfit every day during the company’s town hall last year. He replied, “I really want to clear my life to make it so that I have to make as few decisions as possible about anything except how to best serve the community.”

Ideally, anticipatory design could prevent that paralyzing feeling you get when presented with too many options, like getting dressed in the morning—without requiring you to wear a bland uniform. It could automatically select an outfit for you based on your activities for the day, pulled from your calendar and the weather. It could even make sure your outfit is stylish.

The most compelling reason for anticipatory design in today’s attention economy isn’t just convenience: Anticipatory design also seeks to address the quality of our decision-making, decreasing the number of micro decisions we make each day and leaving brain space to focus on the important matters. “The more things we decide over the course of a day,” Shapiro wrote, “the lesser ability we have to make effective decisions.”

A system of trust

But for anticipatory design to work, an interconnected network of systems and records need to work seamlessly. This means relinquishing personal information—passwords, credit card numbers, activity tracking data, browsing histories, calendars—so the system can make and execute informed decisions on your behalf.

In exchange, Shapiro envisions a highly tailored user experienced based on one’s patterns. “The reality is, design is mass market, but with anticipatory design, data can create experiences personal to me—a user experience for one,” he says, describing a convergence of design and data science. “There’s opportunity to connect all these disparate systems and use data to streamline people’s lives. I think that this will be very transformative.”

Anticipatory design presents new ethical checkpoints for designers and programmers behind the automation, as well as for consumers. Can we trust a system to safeguard our personal data from hackers and marketers—or does privacy become a moot concern? Will companies (or governments) exploit data to forward their agendas? Does creating a fully automated system actually train us to follow more patterns? And what if we don’t want that same brand of soap auto-delivered every time we run out?

Testing in the real world

If this all sounds like the stuff of science fiction, Shapiro points out that anticipatory design is already deployed in the real world. Google Now presents local information based on your travel history and location; Nest adjusts the temperature of your home based on previous activity; and Amazon Dash automatically orders supplies be delivered to your house at a push of a button, saving you a trip to the store.

Of course the ultimate example in development is the self-driving car:

Will anticipatory design—to its full extent—actually catch on? Huge is determined to find out.

Shapiro tells Quartz that his company is building a coffee shop on the ground level of its Atlanta office as a test lab for anticipatory design. In Huge’s experimental coffee shop, baristas will be alerted via an Apple Watch when a customer drives up to the store and will start making the person’s usual order—so that double-shot, nonfat, extra hot latte with caramel drizzle will be ready to hand over the moment they walk up to the counter. Payment will be made automatically via a credit card saved in the system.

Even as we debate how these innovations affect our freedom of choice, design’s role (and limits) in society, and the nature of creativity, the practical conveniences of anticipatory design are undeniably alluring.

And in any case, as Schwartz pointed out as he campaigned for a world with less choices, this hand-wringing is a luxury only available to the privileged. “What enables all this choice is material affluence,” he said (video). “These are peculiar problems of affluent societies. There are many places where the problem is that they have too little choice.”