Comets have always fascinated scientists. Centuries ago it was their glowing tails streaking across skies, and now it is the tantalizing possibility that they may have seeded life on Earth.

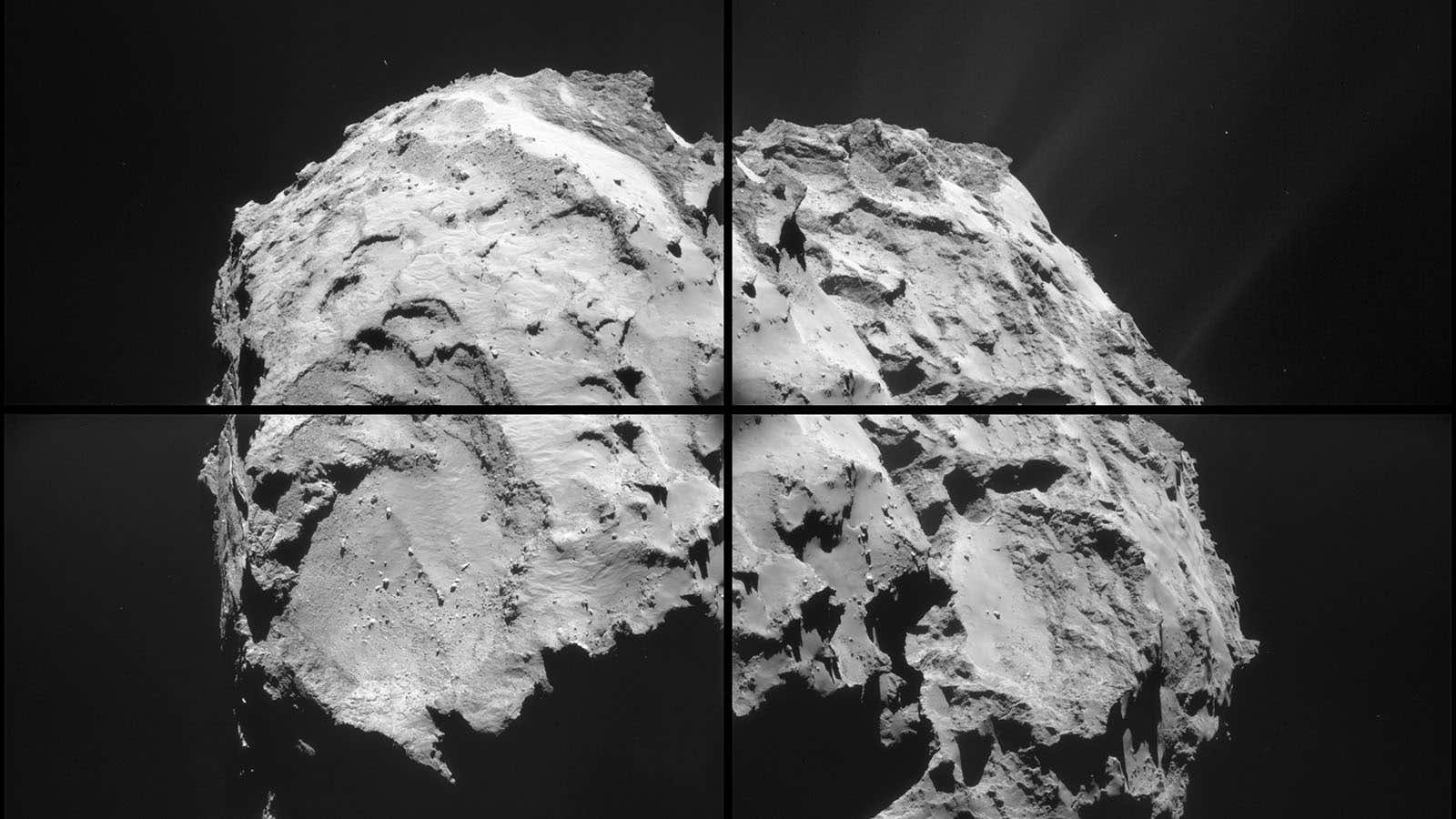

To firm up these answers, it helps to understand the structure of these weird celestial bodies. In its most recent dispatch from comet 67P, the Philae lander has found that, unlike solid-rock asteroids, the comet is mostly porous—as much as 85% of it is empty.

Murthy Gudipati, a NASA scientist, who has worked on understanding the structure of comets, has the perfect analogy: “A comet is like deep fried ice cream. The crust is made of crystalline ice, while the interior is colder and more porous. The organic [compounds] are like a final layer of chocolate on top.”

A February 2015 study tried to understand why comets have this structure, which consists of ice, dust and organic compounds. In an icebox-like instrument, they simulated the conditions that a comet might face as it nears the sun.

The surface temperature of a comet can be as low as -250°C. The ice formed in these conditions is nothing like the ice on Earth. Instead of ordered molecules forming an ice cube, comets have amorphous ice which resembles cotton candy.

For their experiment NASA scientists warmed up the ice from -250°C to -120°C, simulating the warming effects of the sun. As the ice got warmer, organic compounds stuck together and fluffy ice became more structured. This resulted in a hard crust of ice sprinkled with organic compounds, around a much colder, porous center.

This hard crust is probably why the Philae lander bounced off its original landing site on comet 67P, and ended up in a place where it couldn’t get enough sunlight to charge up its battery and send back signals. Even in its misery, Philae taught something new about the most ancient celestial bodies in our solar system.