The tweet may have been sent by the European Space Agency’s humans on Earth, but it is confirmation that their comet lander Philae has woken up and is back in contact.

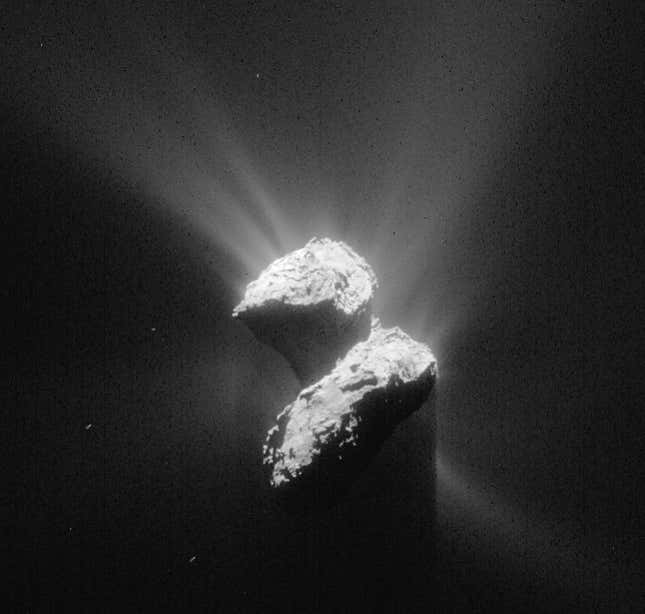

Philae is part of the Rosetta mission that was launched in 2004. After a ten-year journey, in August 2014, Rosetta the satellite settled into orbit around the comet 67P Churyumov-Gerasimenko.

In November, the lander Philae was launched and landed on the comet’s surface. It worked for 60 hours gathering scientific data and beaming it back to Earth via Rosetta. But then its batteries ran out.

There was hope that as the comet approached the sun, Philae would receive enough sunlight to charge up its solar-powered batteries and wake up. After waiting for many months, scientists must be happy that their theoretical prediction has come true.

We still don’t know the exact location of the lander on the comet. But, on June 11, the space agency reported that it might have a location based on images and other data gathered by Rosetta.

In their announcement, the space agency notes that Philae might have woken up earlier, but it did not have enough energy to make contact with Earth. On June 14—its first contact after seven months—Philae sent 300 packets of data back to earth. Eight thousand data packets still remain in its memory. Once they are received and analyzed, scientists will know more about Philae’s hibernation.

Despite the good news, Philae’s time on comet 67P Churyumov-Gerasimenko is limited. As the comet approaches the sun, it will start to heat up, releasing the dust and gases which form a comet’s characteristic tail. Philae will be lost sooner or later, thrown off with the debris or destroyed in the violence.

But scientists won’t be too sad about Philae’s brief existence. It managed to complete a majority of its tasks in the first 60 hours after landing, and any more data that it gathers will be looked upon as a bonus. The knowledge gained by the Rosetta mission is the most we have ever known about these enigmatic celestial objects, observed by humans for centuries but poorly understood until now.