The process of picking running shoes has become absurdly involved. Shoe recommendations intended to help you avoid injury can vary based on age, gender, whether you underpronate or overpronate, and the exact way your foot strikes the ground. Getting the “right” pair now seems to require, at a minimum, a jog on one of those gait-analysis machines and lengthy consultations with salespeople who seem to hold advanced degrees in biomechanics.

A scientific review of decades of research, published last week in the British Journal of Sports Medicine, is calling all of that into question. The lead author of the study is Benno Nigg, an emeritus professor of kinesiology at the University of Calgary and a man the New York Times refers to as “one of the world’s foremost experts on biomechanics.” The conclusion Nigg and his team have arrived at is incredibly simple: Just pick the shoes that are most comfortable.

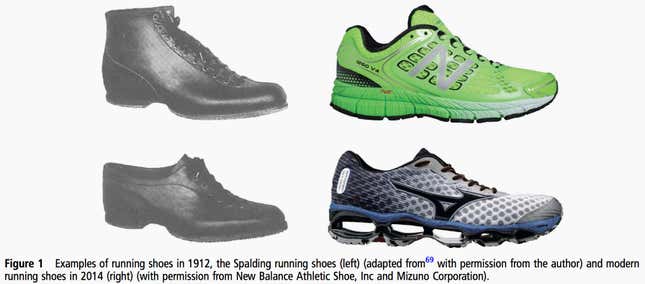

In their analysis, the researchers noticed that despite huge changes in sneaker design and technology, injury rates due to running haven’t changed in the last 40 years. If the evolution of footwear really were making a difference, positively or negatively, it should have been apparent.

The most commonly studied variables assumed to relate to injuries were pronation, or how much your foot rolls inward when it hits the ground, and the impact along your foot from heel to toe when it lands. Looking at the actual epidemiological evidence, however, the claims didn’t seem to stand up. It’s worth noting that the epidemiological studies they found generally had small sample sizes, which the researchers point out doesn’t allow them to draw the soundest conclusions. But the evidence suggested that the “two variables that were thought to be the prime predictors of running injuries are not valid,” the study’s authors wrote.

They also looked at the effects of barefoot running, a popular trend in recent years. One study examined the skeleton’s path of movement during running and found that changes in the subject’s shoes or insoles had only a minor effect. The body seemed to naturally want to maintain its “preferred path of movement,” whatever footwear it was in.

A factor that did appear to make a big difference, however, was comfort. In one study, which Nigg was involved in, 106 soldiers tested six different insoles for comfort. They then got to pick the most comfortable one and use it for the next four months, while a control group without insoles went through identical military training. The test group suffered 53% fewer injuries to the lower extremities than the control group.

Nigg, who has long argued that running footwear doesn’t have much effect, good or bad, suggests that people’s natural tendency to pick comfortable sneakers is behind the unchanging injury rates.

So maybe next time you need a pair of running shoes, try on as many sneakers as you can and jog around a bit. Don’t necessarily pick the pair that’s got the latest technology, or the ones you’re “supposed” to wear based on your gait. Just listen to your body and get the pair that’s comfiest.