The Lutyens Bungalow Zone (LBZ)—a 100-year-old neighbourhood in New Delhi—is perhaps India’s most elite residential location.

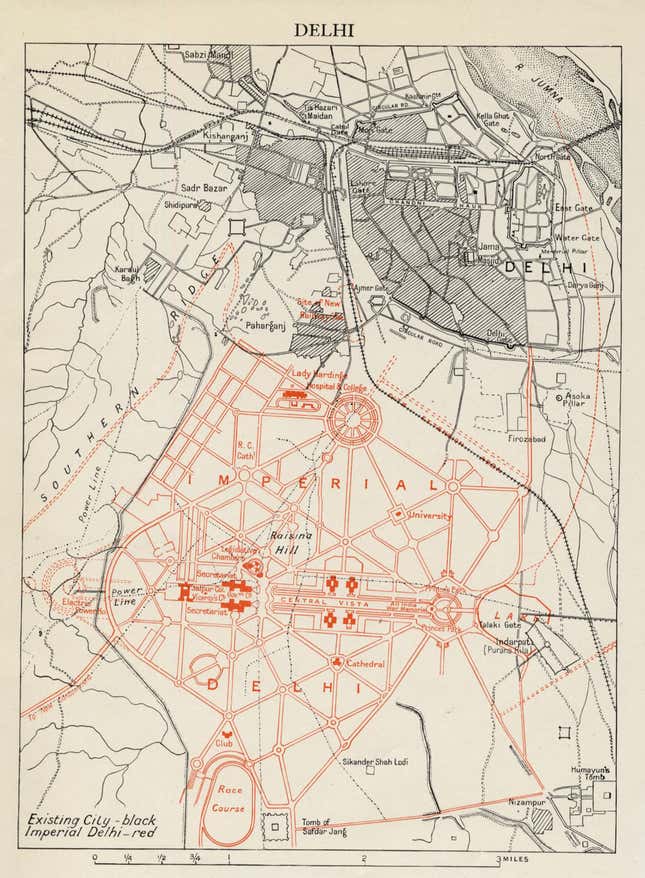

Built by British architect Edwin Lutyens between 1912 and 1930, the 28 square kilometre (sq. km) LBZ boasts of as many as 1,000 bungalows with expansive lawns bordering wide boulevards. These colonial buildings are also home to some of India’s most powerful people: the prime minister, cabinet ministers, bureaucrats and a number of wealthy businessmen.

For the less privileged, however, this stretch of town has almost always remained out of bounds, owing to stringent laws that prohibited high-rise construction in the area. The neighbourhood is also known for its astronomically high real estate prices. In 2014, Mumbai-based Essel Group purchased a 2.8 acre property in the LBZ for Rs304 crore ($45 million). A similar property in Greater Kailash, another affluent neighbourhood in the capital, would cost at least Rs100 crore less.

But all that might change now—at least on the fringes.

The Delhi Urban Arts Commission (DUAC) (pdf)—a government body responsible for ensuring the aesthetic quality of urban and environmental design within Delhi—has suggested to India’s urban development ministry that the LBZ area be shrunk by 5.13 sq. km.

If accepted, the DUAC’s proposal would immediately free up some 1,200 acres of land from the tough construction laws, and allow real estate companies to build more homes in the zone.

The urban development ministry has now sought objections and suggestions from the public, which can be submitted by Oct. 15. Subsequently, the proposal will be discussed with the prime minister’s office.

“Over a period of half a century, the space requirements of the occupants of the bungalows has changed substantially,” the DUAC report said. “By not permitting more built-up area, illegal extensions may be an outcome. The commission felt that this can be tackled by taking a liberal approach and permitting development/redevelopment in a calibrated manner.”

The DUAC, after a five-month-long study, concluded that a number of adjoining areas, which were not part of the original LBZ, could be jettisoned. The original LBZ area was spread across 19.12 sq. km, which was increased to 25.88 in 1988, and then to 28.73 in 2003, to accommodate parts of diplomatic areas of Chanakyapuri and other localities, including Bengali Market and Panchsheel Marg.

Under the new proposal, upmarket areas of Sunder Nagar, Golf Links, Jor Bagh, Bengali Market, Panchsheel Marg, Sardar Patel Marg, Mandir Marg, Chanakyapuri, Ashoka Road and Connaught Place could be excluded from the LBZ.

The DUAC had swung into action after several politicians demanded more space for their state government’s buildings in the LBZ.

The plan

Compared to the rest of Delhi, where some 1,100 to 1,600 people live per acre of space, LBZ has a population density of between 14 and 15 people per acre.

Current rules do not allow for high-rise constructions, since the bungalows have a heritage value. If an old bungalow is to be reconstructed, it has to retain the height of the original structure. Lutyens Bungalows are usually six metres high.

Now, DUAC recommends that residential properties in the entire LBZ should be allowed to be built up to 12 metres with basements. And commercial buildings should be permitted to go to up to 32 meters—about eight floors—with a three-level basement.

“The rationale for these development control norms is that while development is necessary, in order to meet growing demand for space, the same has to be carefully orchestrated since the LBZ is a historic precinct of architecture and town planning having heritage value of universal nature and unique in character, with a high degree of aesthetic value,” the DUAC said. “It is a unique example of a garden city residential ‘bungalows’ in the whole world and needs to be carefully conserved.”

Booming real estate

The opening up of the LBZ will mean more opportunities for real estate developers—and a possible drop in realty prices.

“The cost of a plot may go up as one can construct more in a given area, apartment prices may come down because of higher supply,” Anshuman Magazine, chairman and managing director of real estate consultancy firm CB Richard Ellis South Asia, told the Business Standard newspaper.

“Not only will the proposed rules allow new high rises with better facilities to come up, it will also provide value for money to buyers. As of now, despite high prices, the space is restricted for construction,” Ashwinder Raj Singh, CEO of residential services at property consultant JLL India, said in a note.

“While Delhi’s purists will not agree,” Singh added, “its ‘commoners’—and most especially the city’s real estate market—are looking at an unmitigated boon.”