More than a billion people around the world rely on smartphones and their ubiquitous messaging and social media apps, but none more so than the hundreds of thousands of people who are fleeing war, hunger, and famine in the Middle East and Africa.

The massive crowds of refugees and migrants from Syria and elsewhere who have flooded Europe this year, and continue to arrive en masse, are relying heavily on smartphone apps such as WhatsApp, Viber, and Facebook Messenger, along with other tools like Google Maps, as they risk perilous sea crossings, skirt unfriendly border crossings, and try to keep in touch with their loved ones.

“Our phones and power banks are more important for our journey than anything, even more important than food,” a Syrian named Wael told Agence France Presse on the Greek island of Kos.

Clothes and food can be purchased relatively cheaply, and even cash can be electronically transferred, but a smartphone is crucial. Smugglers who take the refugees across the Mediterranean drastically limit what people can take on board, but the phones are too precious to give up, they say.

A marine distress beacon

One Syrian man described to the International Rescue Committee, an organization that provides refugee relief, how he used his phone to try to contact the Greek coast guard when his boat was sinking.

The engine of the overcrowded dinghy he was on had died after half an hour of sailing. “We were exactly between Turkey and Greece. I know because I checked the GPS on my phone,” he said. Then the weather started getting worse:

Quickly the boat became full of water and started to sink. I rang the Greek coastguard and started shouting ‘help us, help us’ but they couldn’t really hear me because my phone was wrapped in a plastic bag to protect it from the water. So I sent a Whatsapp message giving my GPS and asking them to help us. I also sent my family a message with my GPS and explained the situation but said ‘don’t worry, even though the weather is bad, we’ll make it across.’

He ended up jumping into the sea, and survived.

Facebook as a travel agency

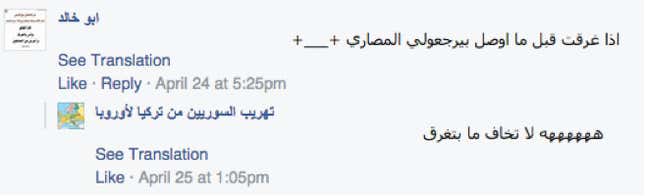

Before they head out on the dangerous journey across the Mediterranean, refugees and migrants find smugglers through WhatsApp and Facebook pages that function as illicit travel agencies. Travelers also use Facebook pages to share crucial information, such as which smugglers charge less.

Smugglers can take deceptively beautiful pictures, and promise a journey in great conditions. After the migrants pay the traffickers often exorbitant sums, they arrive to see a rickety dinghy, instead of a comfortable boat.

“On the one hand they are very liberating technologies, but there’s a very dark side to them, because there are un-policed, unregulated, and have unscrupulous people taking advantage of them,” Leonard Doyle, a spokesman for the International Organization of Migration, tells Quartz.

“Facebook, to their great credit, are paying attention and shutting the pages down immediately,” says Doyle.

However, new pages quickly replace the ones that are shut down. And, Doyle says, with the spread of mobile technology, the exploitation of migrants and refugees through social media will only get worse. Facebook Zero, for instance, he says, a basic mobile version of the platform that doesn’t require a data plan, will continue to bring smugglers access to a wider, less educated, poorer population.

Facebook, in a statement to Quartz, said: ”It is against Facebook’s community standards to post content that coordinates people smuggling and this type of content will be removed when reported to us. We encourage people to use the reporting links found across our site so that our team of experts can review the content swiftly.”

A map, a guidebook, an instruction manual

By texting and messaging with their friends and family who had taken the journey before them, refugees find out exactly what to do when they arrive at their destination, and precisely where to go.

Paul Donohoe of the International Rescue Committee (IRC) told Quartz what refugees who arrive on the Greek island of Lesbos do when there is no bus available. “They literally just turn left, and start walking–they’ve had it all communicated to them.”

Once on land in Europe, GPS can be better than an unscrupulous guide. One man trying to get from Greece to Macedonia used his phone to cross the border, using a digital map “to find the best road to reach the nearest train station on the other side of the border,” he told the IRC.

Power is power

While smartphones play a crucial role in the refugees’ journey, they are also prone to breakage, theft, and battery loss. What struck Donohoe most while he was at Lesbos, was that “everybody, in addition to sorting out their shelter, food, water is trying to get electricity for their phones.”

Humanitarian organizations have noticed how important phones are for the refugees. The IRC has handed out thousands of solar-powered chargers in Lebanon, Iraq and Syria. The United Nations refugee agency gave out 33,000 SIM cards to refugees in Jordan. The Civil Society and Technology Project sent in human Wi-Fi beacons into crowds of refugees: volunteers equipped with hotspot-emitting backpacks.

Selfies are universal

Smartphones aren’t just about survival for people trying to reach a better life in Europe. They are also a means for celebration:

The newly arrived take pictures to send to their relatives or they pose for jubilant selfies, the eponymous form of photography promoted by Instagram celebrities. Sometimes a selfie stick accessory provides a better angle.

Refugees: They’re just like us

In addition to serving as a lifeline during their journey, a refugee’s smartphone can serve another, unexpected purpose. It can show their European hosts, many of whom are wary of the influx of newcomers, that the people who are camping out at ports, train stations, and cafes, trying to catch Wi-Fi signal are not that different from them.

As the Independent’s James O’Malley wrote this week: “Surprised that Syrian refugees have smartphones? Sorry to break this to you, but you’re an idiot.”

“I think there is an understanding that the cultural distance isn’t that great and things like technology show that proximity,” says Donohoe of the IRC. Just observing the refugees’ level of English and their ability to communicate fosters a sense that ”they could be us,” he adds.

Donohoe describes how he sat in cafes or restaurants in Lesbos, relying on their Wi-Fi for work. Next to him, refugees would be using the same Wi-Fi to speak to relatives back home.

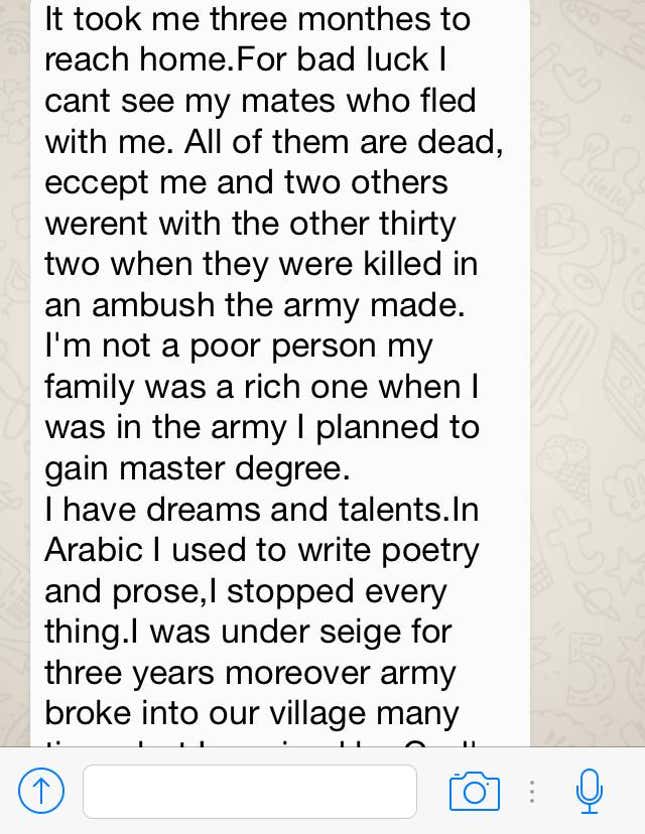

But there’s a flip side, Donohoe says: “You hear people saying: ‘Are they that desperate if they have a smartphone?’ There’s a sense that “if you have any extra kind of product you are not deserving in some way.” What they don’t realize is that many of these people are educated and were well off, back home, in Syria for instance, but were forced out by a brutal war. As The New York Times notes, the use of technology on the run is largely driven by tens of thousands of middle-class Syrians.

What’s more, cheap smartphones are widely available, and internet capable phones are increasingly popular in developing countries: in Jordan, 41% of people surveyed by the Pew Research Center own a smartphone, in Lebanon, 48%.

The odyssey of Ideas

Sam Nemeth, a Dutch journalist, has been following the journey of a Syrian man nicknamed “Ideas” by messaging with him on WhatsApp.

Ideas has made his way through Greece, Macedonia, Serbia, Hungary, Austria, all the while documenting his trip on his phone, and sending updates to Nemeth who posts them on a blog and Facebook group called ”Ideas travels: a Whatsapp odyssey in the Balkans.”

According to Nemeth and Ideas, WhatsApp is so popular among the Syrian refugees, because it was widely adopted in the country after the Assad regime shut down Skype.

Ideas tells Quartz, via email from Nemeth, that without WhatsApp it “would have taken him much longer and the risks of being arrested or robbed would have been much higher.” In many cases he was guided by messages from other Syrians.

Ideas got his refugee status in the Netherlands at the end of August, he told Nemeth through WhatsApp. His arrival was cheered on Facebook by Westerners who have learned of his story.