United Nations member states are expected today (Sept. 25) to adopt a set of 17 goals for ending poverty, fighting inequality, and tackling climate change by 2030. That follows a similar exercise in 2000 that established goals for 2015—an effort that is generally credited with yielding serious gains in areas such as child mortality and access to clean water by helping focus aid and government attention.

Bill Gates has been outspoken about why people should be paying more attention to the goals—known as the sustainable development goals (SDGs)—being adopted today. In recent pieces he wrote for Quartz related to the topic, Gates explained how 34 million lives could be saved over the next 15 years by tackling just three health issues, argued for extending the fight against child mortality, and cautioned against reducing foreign aid to the booming economies that are still home to many of the world’s poorest people.

Quartz caught up with Gates this week to talk about why he believes the development goals are so important, how he assesses their renewable energy targets, and what needs to be done about the current Europe refugee crisis. What follows is a transcript, lightly edited for clarity.

Quartz: How would you describe the importance of the setting of the millennium development goals (MDGs) in 2000?

Bill Gates: It made a fantastic difference. Because it really highlighted the measures that you can look at country by country. And amazingly, instead of all the measures tracking your level of wealth, you see some countries who reduced childhood deaths even when they were very, very poor or who got women into education. So we were able to really encourage better measurement, really highlight those numbers. Heads of state or other people would be talking about these things, every country would have a sense of who’s doing the best job in this area and how are they doing it. Particularly if it’s someone at your level of wealth that’s doing it far, far better. Take for example primary health care in Ethiopia versus primary health care in Nigeria, where Nigeria is quite a bit richer than Ethiopia, but does a far, far worse job and therefore has well over twice as many children die per capita. So the MDGs really got a clear message for the coordinated donors and NGOs and UN agencies, and got governments to see it as a kind of report card.

Is this the most important thing that the UN has done in the last 15 years?

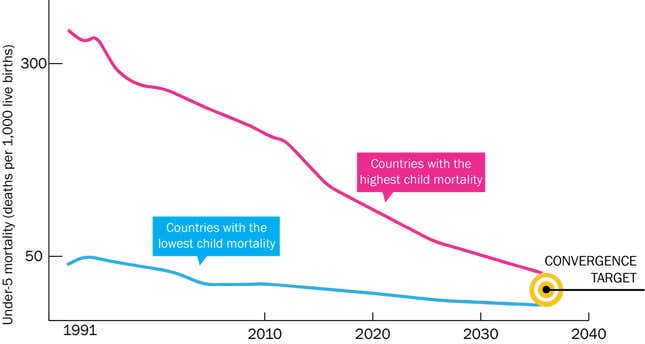

BG: Absolutely. There may be some war intervention that is very, very helpful because peacekeeping is one of the UN’s functions, but on an ongoing basis year to year, the cutting of childhood deaths in half [is very significant.] The rate of death at the baseline that they measured from 1990, that was over 12 million a year, and now we’re well under six million a year. What that means, family by family, is pretty phenomenal.

If you would do those health interventions, it’s not just the kids whose lives are saved, it’s the health improvement in terms of the nutrition and less disease that allows kids to develop physically and mentally and then make full contributions that eventually, with the right policies, allow countries to move from being poor countries to being middle income. We’ve seen a lot of that, and over these next 15 years the vast majority of the poor countries will move up. Just taking the best practices, the poor countries, almost all of them will move up to be middle-income countries. If we just carry forward that effort into more countries, the best practices, then we can achieve the SDGs as well.

The UN itself highlighted some areas including maternal, newborn, and child health, and reproductive health as areas where they are “off-track” from the 2000 goals. If you take the goals and the targets literally, progress has been uneven. Is that a fair assessment?

BG: Yes. But let’s take childhood death in particular. The goal was to reduce it globally by two-thirds; what they actually achieved was cutting it in half. And so that’s pretty fantastic progress. The goal was set to be super ambitious, and that’s over a 25-year period. You know, confusingly, even though the goals were written down in 2000, the numeric base-period for the goals is 1990. We did get concrete numbers into the SDGs and what they represent is trying now in 15 years to do what we did in the last 25—that is cut childhood death in half again, which would get it to below three million children a year.

When you break it down country by country, you can actually see ‘Hey what did Ethiopia do? What did Rwanda do? What did Tanzania do?’ If everybody’s like China—that is you have to get rich to improve health—that’s very hard to do. But in fact these countries, even though their economic growth wasn’t dramatic, their health improvement in all three cases was very dramatic. So there are clear things that can be done that we just have to take those to the rest of the countries.

How would you characterize the relative importance of the new set of goals?

BG: It’s important to have goals for how the poorest in the world are uplifted and how we get some sense of global equity and having a measurable agenda about global equity, where every country has a goal. Goals for the rich countries in terms of innovation and resources, even now middle-income countries like China, Mexico, and Brazil reaching out to help poor countries, and then the poor countries themselves, where they are going to have more domestic resources and their policies make a huge difference in these results. So, you know, we definitely needed to renew the MDGs.

We could have just left the aid alone and made more ambitious targets. But in fact, a number of key issues weren’t in the MDGs, for example anything related to the environment was being handled separately. Now they are integrated in, which is very appropriate because you have to maintain the environment to be able to get agricultural productivity up and to get malnutrition down. Because the MDGs were successful, and the way UN documents and processes work is very committee-oriented, the fact that it got quite a bit [longer] is not surprising.

But I actually think it’s pretty well written. It’s pretty succinct. The first six goals basically mirror the first seven goals that we had in the MDGs and a lot of the additional goals are environmental-related goals. It didn’t look like they would have specific targets for some things and we were very involved in making sure that in the core areas like childhood death and maternal death we succeeded in getting very specific target goals into the documents. So I think that will be very helpful to us.

There are more than double as many goals as the last time. And one of the concerns is that there is less focus and it’s harder to track progress against them because there are so many targets. What’s your level of concern about that?

BG: The sovereign countries really decide to set their goals and there are some of these things, like the environmental thing, that are more for the rich countries in terms of their innovation and their own practices to lead the way. You know, we really shouldn’t put those constraints on the poor countries, who don’t do much greenhouse gas emissions. So, if you look at an individual country, it’s pretty clear what the priorities should be. And for the poorest countries, that’s mostly going to be the first six, which are the carryover MDGs.

Anyway, having the 17 is just fine. Most people would look at those and think they are quite reasonable. And some of the newer goals are harder to measure—with the MDGs they were tough to measure—but because they were goals we got involved. How do you measure improvements in sanitation or access to clean water? Even in the education goal in the MDGs, they didn’t do as much about making sure the education was high quality, as opposed to just enrollment. And so for the goals that have been around, the ability to do per-country measures and make sure the quality piece is in there, we’re a lot better at that. Some of these goals that are new, they are just figuring out how to do measurement. But it’s good! You know, they’ll get down the learning-curve on those goals.

Several of the new goals are around energy and environment, as you said. And you signaled over the summer that renewable energy is an area of increased focus for you personally. How would you assess the global goals in this area, including because the targets as currently written seem fairly high-level?

BG: Yeah, obviously the SDGs are high level about the environmental goals and then there’s a specific process, including this upcoming COP meeting in Paris that will be far more concrete, where they’re saying we’re trying to limit the warming to two degrees centigrade and trying to get a series of commitments from people that as they get tightened over time manage to achieve that. That process is trying to be very, very concrete and so it’s good that this general assembly process to some degree delegated the commitments and goal setting to that other process because it’s an area with plenty of complexity.

Unlike with childhood deaths, the real action is in the rich countries and the middle-income countries, where they have to change their transport and energy systems. And the only way we’ll achieve those goals is through massive innovation. We have to pursue lots of paths of innovation, including some early-stage stuff that government research needs to fund because it’s basic research, and including some stuff where you have to have private investors who are willing to invest in very risky new things in order to prove them out.

But if all we have is today’s technology, we would not be able to achieve any reasonable climate goals. I’ve been part of a group pushing for more government R&D in energy for over six years. But I’m being particularly active on that front because I feel like having that on the agenda of this big meeting in Paris where all the countries, particularly the rich countries, are saying to each other ‘Let’s mutually commit to drive innovation,’ both government research money increases and drawing in private capital appropriately. And I do think for the first time that is going to be discussed at the COP. I think that by having it on the agenda, as we have future meetings, that discussion will become richer and richer and more and more concrete. It’s kind of unfortunate it hasn’t been a part of the discussion, but in meeting with a number of the people who are involved in this meeting, there is some excitement to get that on the agenda. Both for the COP itself, and for the related meetings around it.

What’s your biggest concern about the new global goals? What would be your own area of criticism?

BG: The biggest problem we always have is that because the poorest are not nearby, people who live in rich countries are not exposed to the dire conditions and the progress we’ve made in reducing that, and the need to stay committed. So it’s always a problem of visibility. If we had malaria in Seattle, people would take action. We saw the irony of this even in the ebola epidemic, where having a few people sick in the United States galvanized a level of interest and attention way beyond having the deaths taking place over in Africa.

That is human nature, and by educating people, using the internet to let them see and read about what’s going on— we need to bridge that gap so that our sense of humanity is still operating despite the large distances involved.

With the SDGs we’re going to declare these things and we’ll have a big week in New York and it will get some visibility. My biggest concern is, will it continue to be visible? Like take the presidential election—will generosity in terms of development aid even come up in the US presidential election? Or will this stuff in some ways be neglected? So I think as a document, it’s just fine; I was really pleased. The thing we really pushed for was the concrete health goals and those did get in there, so I think it’s a great agenda for the next 15 years.

One question is how to pay for the measures to achieve the global goals, and one component of that has been fighting tax and trade fraud. The US and UK have been blocking some of the anti-tax evasion measures that would require more transparency, seemingly because multi-nationals here and in Europe benefit from them. This is a problem isn’t it?

BG: I’m not an expert on tax stuff. But there needs to be global coordination between various countries so that you don’t have double-taxation and you don’t have zero taxation. And anything that’s global is very complicated to achieve. You’d think that Europe and the US could have coordination on, say, how they look at corporate profits and make sure that nobody’s being over-taxed or under-taxed, and then make sure that the poor countries aren’t missing out on tax-revenue opportunities because of the way things are structured.

Yes, I think that the US and the UK and others need to be more aggressive in looking at changes and looking at transparency. I know some NGOs have been pushing this pretty hard—but the only area we’re directly involved with is the question of raising taxes in the poor countries themselves, and including making sure that the mineral deals they do, that there’s transparency on that. We have been involved in that piece of it.

The global goals draft mentions “the positive contribution of migrants for inclusive growth and sustainable development.” This feels pretty far from what we’re hearing out of Europe these days. Do you think governments are responsibly handling the current refugee crisis in the Middle East and Europe?

BG: Well, the term ‘migrant’ is a broad term that covers the wonderful fact that remittances are, for most countries, even larger than the aid going into that country.

When you have huge emergency flows of people, that’s far more difficult. And here you’ve got over four million people leaving Syria. The percentage of those four million that can make their way to richer countries, it’s maybe only going to be 10% or 20%, even if you’re super generous. You’re still going to have the need to get rid of the thing that’s creating the refugees and you’re going to have to have regional refugee camps that are very, very good. The fact that in the long run, migration is beneficial to a country, it’s unfortunate that there’s such a strong set of people who are not convinced of that and we see it in almost every country. And I think it’s an act of leadership to be like Chancellor Merkel, explaining that both in terms of human compassion and in terms of long-term well-being, that migrants handled properly are a very, very good thing.