Bill Gates: Keep up the momentum against child mortality

In my Quartz piece last month, I wrote about how the world could save 34 million lives by investing in simple, broadly available methods for treating tuberculosis; preventing the spread of HIV/AIDS; and saving mothers from dying during pregnancy or childbirth.

In my Quartz piece last month, I wrote about how the world could save 34 million lives by investing in simple, broadly available methods for treating tuberculosis; preventing the spread of HIV/AIDS; and saving mothers from dying during pregnancy or childbirth.

Invest in those three areas, save 34 million people. Pretty powerful, right?

Well, there’s something we can do to save even more lives.

One of the most basic measurements of global health is the child-mortality rate. On this front, the world has made exceptional progress over the past half-century.

In 1960, about one child in five died before his or her fifth birthday. By 1990—a quarter-century ago—that rate had been cut in half, to one in ten.

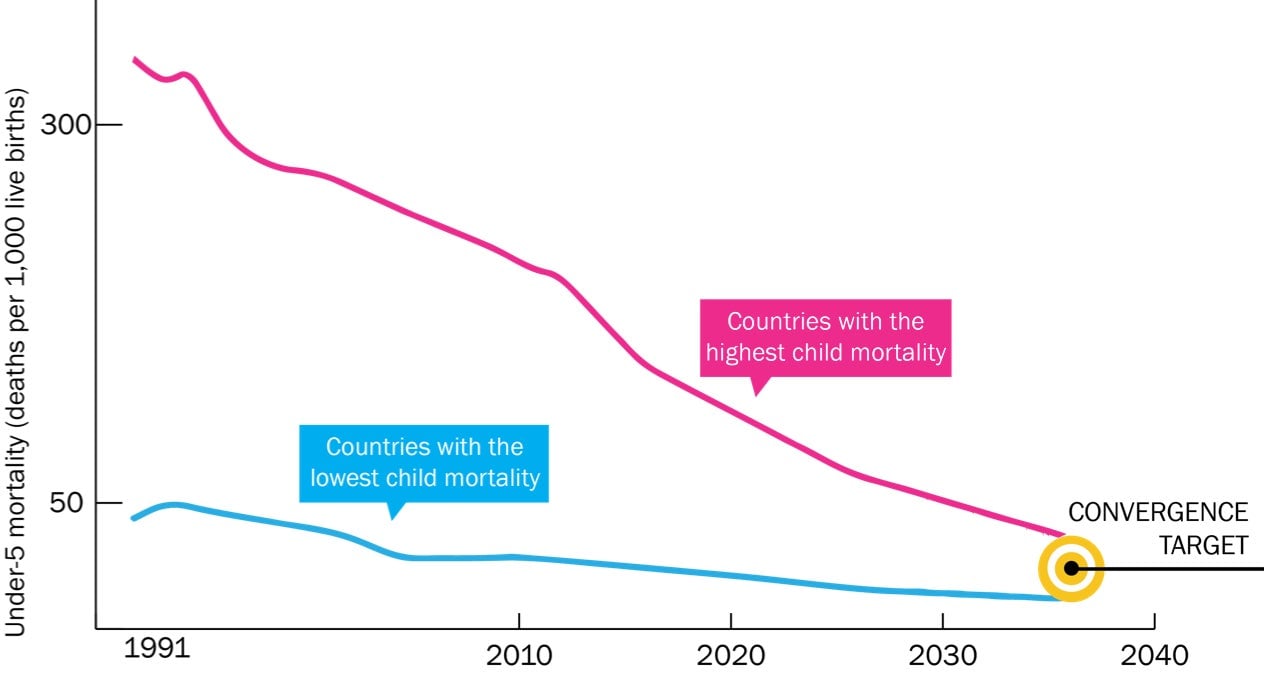

Since then, it’s been cut in half again, to one in 20. In our annual letter this year, Melinda and I went on the record to predict that within a mere 15 years, we can cut this rate at least in half again—to one in 40, or even better than that.

This would be an enormous achievement. However, just because a steep further reduction in child mortality is possible does not mean it is guaranteed.

The progress of recent decades is partly due to the world’s willingness to identify this area as a top priority—and to set clear and meaningful goals for improvement.

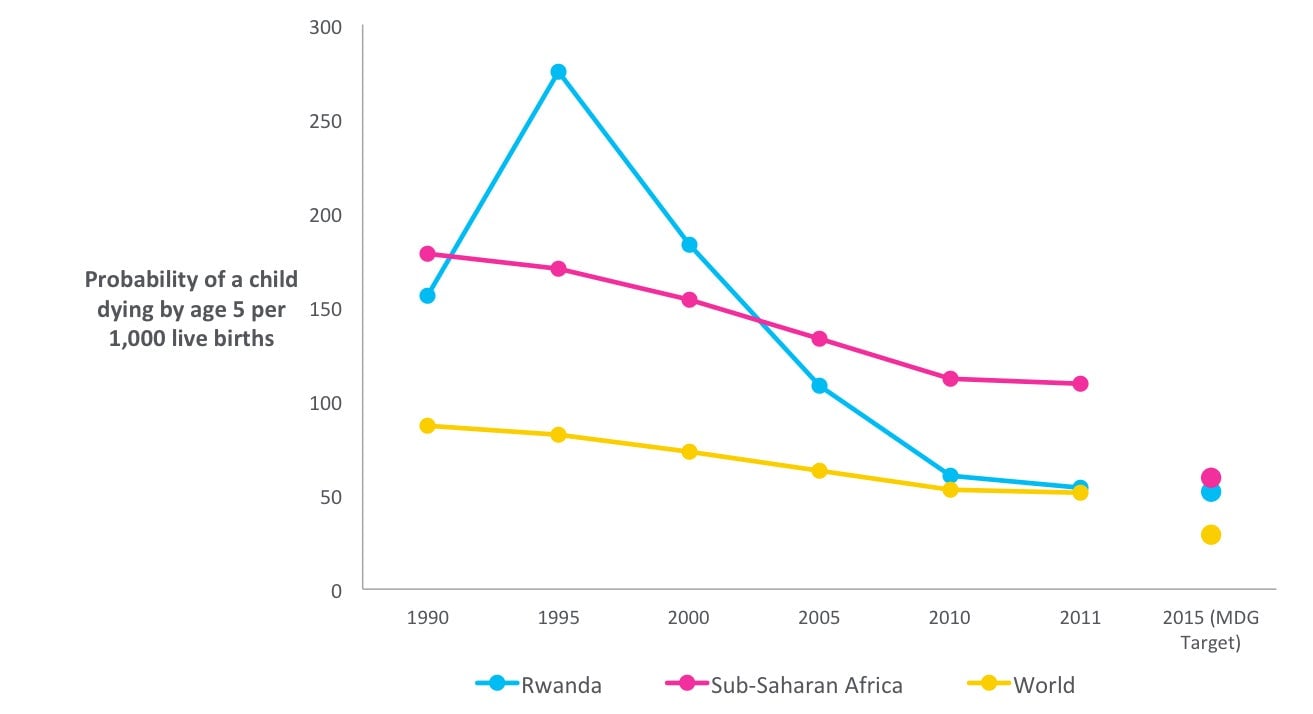

At the start of this century, nations adopted the Millennium Development Goals (or MDGs), which set clear aims for reducing extreme poverty and fighting disease. One of the most successful of the MDGs focused on reducing child mortality by two-thirds.

Some of the poorest countries in the world—including Ethiopia, Tanzania, and Malawi—used the MDG standards to achieve historic improvements in child health. The MDGs expire this year, to be replaced in September by a new set of objectives known as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

It’s vital that the new goals keep child mortality as a primary area of focus—and that they establish clear, aggressive benchmarks for further progress.

It’s an opportune moment to think about how the world should define its aspirations regarding child mortality. Health ministers just concluded their meeting in Geneva at the World Health Assembly, and my own hope is that the world’s governments will use the coming weeks and months to set very specific, measurable standards for reducing child mortality—and for assisting the poorest nations in meeting those targets.

There is still much further to go in reducing child mortality—and the most effective path forward is no mystery.

That’s because preventable causes such as diarrhea, pneumonia, malaria, and pre-term birth account for 83% of all childhood deaths. (Injuries and non-communicable conditions such as congenital defects account for the bulk of the rest.)

In other words, the vast majority of childhood deaths worldwide result from causes that we know we can beat—because we’ve already beaten them here in the US and in other affluent nations.

However, we need to summon the will and the resources to get the job done. In particular, we must contend with the problem of malnutrition. When a child dies anywhere in the world, malnutrition is an underlying cause almost half the time. This strong link between malnutrition and child mortality is a major reason why our foundation is committing to a new nutrition strategy that focuses on the nations where the need is greatest.

Another aspect of child mortality that requires more attention is the fact that death rates among newborns have stubbornly failed to improve as quickly as for slightly older children.

Each year, nearly three million newborns die in their first month of life. Most of these deaths could be prevented with proven, inexpensive solutions such as immediate and exclusive breastfeeding; umbilical-cord care to prevent infection; and skin-to-skin contact between mother and child.

We know that further progress on child mortality requires a continued commitment by the world’s governments—but it also requires the involvement of active, informed individuals.

To lend your voice to the conversation about how to accelerate progress on child mortality and other urgent global health and development issues, I encourage you to become a Global Citizen.