“I can see you are a very talented designer who ought to be looking forward,” wrote Laurence Mead, the managing director of United Nude, to Iskander Asanaliev in March 2014.

That was one of the last friendly things they said to each other.

The running feud between Asanaliev, a 31-year-old freelance designer from Kyrgyzstan, and United Nude, a global footwear company that boasts flagship stores in London, Amsterdam and New York, is a parable about the creative professions in a globalized, internet-connected world. It’s a story of how hard it is for independent designers to enforce their intellectual property—and for companies to defend against slanderous claims of intellectual-property theft. It’s a tale of egos, misunderstandings, and the fuzzy boundary between inspiration and imitation.

And, ultimately, it’s about heels.

The tale begins in the summer of 2009, when Asanaliev—whose portfolio runs the gamut from watches to shoes—won third prize in a competition sponsored by Ars Sutoria and Domus Academy, two design and fashion schools in Milan. The prize entitled him to 60% off tuition fees for a Masters course in accessories design at Domus.

As life in the Italian business capital can be very expensive, Asanaliev—then living in Turkey—had, in parallel to his Master’s application, started looking for sponsors. He had put out feelers to various large shoemaking brands, United Nude among them, about the possibility of commercializing his models. “If that worked out, I thought, I could afford to study at a top Italian school and improve my skills,” he told me when we first met last spring, in a café in the Kyrgyz capital, Bishkek.

At first he had no luck. But when he wrote to United Nude again after winning the prize, the response was more encouraging.

“I spoke to Rem D Koolhaas, the creative director of United Nude, about you previously and he has asked to look at some of your work before responding,” wrote Dory Benami—at the time, the company’s executive vice president and chief legal officer—on June 26, 2009. He invited Asanaliev “to send something for me to pass on to him [Koolhaas] to review.” (Rem D. Koolhaas is the nephew of the renowned Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas.)

On July 8, the Kyrgyz designer forwarded the same portfolio that had earned him third place in the Ars Sutoria contest. The following day, Benami acknowledged receipt of the material: “I will let you know what the response is when I receive it.”

2011: first round

As the weeks turned to months, Asanaliev assumed that UN wasn’t interested. In time, he gave up on the idea of studying in Italy and moved back from Turkey to his native Kyrgyzstan.

At the time, the country was reeling in the aftermath of a series of high-profile killings, suspected to be the work of ex-president Kurmanbek Bakiyev, who was then ousted in a popular revolution in 2010. Busy starting a new life amidst political instability, Asanaliev had all but forgotten about UN.

However, on March 10, 2011, he chanced upon UN’s spring/summer 2011 collection on the internet. It included the Spike, a woman’s heeled sandal with straps that loop their way from toe to ankle, at one point diving down to the bottom of the heel. “I remember seeing UN’s Spike model and thinking: no way, this is my design,” Asanaliev recalled, while sipping ice tea as if to wash down his angst.

In fact, the Spike was the second UN shoe that looked familiar to him. “A few months after sending my portfolio to UN, I’d come across another model—the Frame—whose heel closely resembled one of my designs, but at the time I didn’t pay too much attention to it. I thought I was being paranoid,” he continued. “Now I was positive: they’d appropriated my idea without my consent. They basically lowered the heel and removed one strap in front, and that’s it.”

The same day, Asanaliev emailed Benami asking him to explain the seeming similarity between his designs and two of UN’s models. When there was no immediate answer, Asanaliev’s emails grew more angry and frustrated. He threatened to take UN to court and, crucially, to “hurt” Koolhaas’s reputation. In a desperate and arguably rash move, on March 15—just five days after his initial email to Benami—he posted a lengthy blog entry entitled “How Rem D Koolhaas stole my design for his United Nude,” detailing his version of the story. He used the equally unsubtle URL, remdkoolhaasisathief.blogspot.com.

UN’s official reply came in a March 24 letter. In it, Benami said that the company could not have copied Asanaliev’s designs. Though the Frame went on sale only in December 2009, he said, “[t]he first prototype of The Frame was made in February 2008 and sales samples were made in April 2009”—well before Asanaliev sent his portfolio to UN in July. As for the Spike, it was “a lower heeled version” of an older UN shoe—the Cosmo, which had gone on sale in 2008. The letter concluded that “your accusations are not only unfounded, they may be subject to both civil and criminal liability.”

The problem of provenance

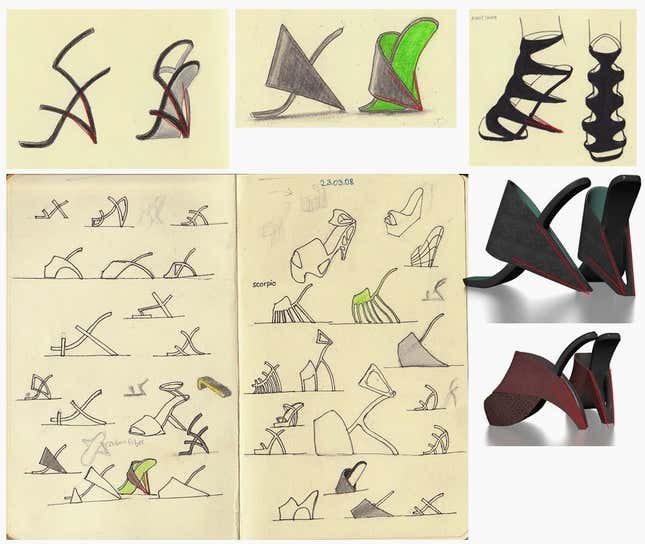

A look these graphics that Asanaliev produced for Quartz, comparing the United Nude models with some of his own designs, instantly makes clear the difficulty in settling claims of authorship. There are countless shoe designs, but only so many possible ways to arrange heels, straps, and curves. To the layman’s eye, Asanaliev’s sandal does indeed look similar to the Frame and especially the Spike. On the other hand, it also looks pretty similar to the Cosmo—a model that, as he acknowledges, predates his design.

A specialist’s eye, of course, sees things differently. Asanaliev contends that the telltale link between the Frame and his shoe is in the heel: It consists of two pairs of struts that descend symmetrically from either side of the sole to meet at a point. The Spike, similarly, has a double-heeled design. “Never before the Frame” did UN design a similar heel, he contends. In the Cosmo, by contrast, the heel consists of just one strut on each side, and they are at an angle to one another, making it asymmetric.

Three designers contacted for this piece also confirmed to Quartz—on the condition of anonymity—that striking similarities exist between Asanaliev’s sketches and UN’s creations. One went as far as speculating that, in the modern fashion world, “everyone copies. Real creativity doesn’t lie in copying, but in knowing how to copy.”

For his part, Mead, UN’s managing director, in correspondence with Quartz, acknowledged that ”there are indeed similarities between the United Nude shoes and the shoes in the pictures sent by Mr Asanaliev, but it is not clear which inspired which or whether in fact they were developed at the same time.” However, this was not an admission that UN might have copied the Kyrgyz designer’s work—quite the contrary. ”No doubt Mr Asanaliev had seen United Nude shoes before he submitted his designs to the company so it is entirely possible that the reverse of his claims is true, and that Mr Asanaliev was in fact inspired by United Nude.”

Mead also sent Quartz a copy of the company’s “look book” for spring/summer 2007. It “clearly shows other United Nude designs which were the inspiration for our Frame design,” he wrote. These include a shoe called the Porn (later renamed the Loop) which he says was developed in mid-2006 and delivered to market in January 2007.

Nonetheless, with so much room for differing interpretations, perhaps the only way to establish a design’s originality for certain is through a paper trail. And according to UN, such a paper trail exists. Benami, in the March 24, 2009 response to Asanaliev, wrote that there is an “extensive catalog of prototypes and designs in [UN’s] archives that demonstrate that both the Frame and the Spike shoes were designed by United Nude prior to any correspondence with you.” Despite several requests from Quartz, however, Mead didn’t provide material from the archive Benami mentioned.

Asanaliev’s blog post received thousands of hits in the first few weeks, coming at the top of Google searches for “United Nude Rem D Koolhaas” (it still does). UN, understandably, reacted sharply. “If you do not immediately remove the information you have posted, we shall take legal action against you for libel,” Benami wrote.

2014: second round

But Asanaliev did not take down his post. And despite its threat to sue him, UN appeared to let the matter drop. Then, in March 2014, almost three years after the post went up, Mead unexpectedly reached out to Asanaliev. (Asked why, he told Quartz: “I contacted Mr Asanaliev when I did because his blog post came to Rem’s attention (again) and he asked me to deal with it.”)

On and off over several weeks, the two exchanged ideas over Skype chat on how to find a mutually satisfactory solution to their dispute.

Things seemed to get off to a good start. Mead first offered $1,000 as a token fee and, when Asanaliev objected, he proposed a 5% royalty on total sales of the Spike. There was even talk of possible future collaborations.

Mead made it abundantly clear in the chat that this would be an “in good faith agreement” and that UN didn’t accept “the premise that the design was a copy.” Both parties, however, seemed willing to put the unpleasant episode behind them. As a sign of good will, Asanaliev took down the blog post on March 6.

Alas, this attempt at reconciliation collapsed. “After much discussion I have to advise you that [Mr Koolhaas] is adamant that there was no breach of trust in anything that UN did,” Mead wrote on March 25, adding: “He is adamant that your designs were not copied nor were they the inspiration for the shoes which you claim were copied. I am therefore not able to offer you anything other than an apology for any distress that this whole issue has caused.”

Asanaliev was incensed. In a Skype chat with Mead, he called the initial offer a “trap” to convince him to take down his blog. (Mead insisted that no, it had been made in good faith.) He threatened to re-post the blog—which he did, and it’s still up there—and challenged UN to take him to court, declaring that in Kyrgyzstan “the rules of the world don’t work.”

So, what now?

The case of UN and Asanaliev seems emblematic of the problems the creative industry grapples with as it adjusts to a fast-paced, globalized world. As Mead himself told Quartz, “it is extremely difficult to know exactly the provenance of a design in an industry like shoemaking which is so prolific in its output.”

A partner at a top New York firm confirmed that “the claims you are describing, I’m afraid, are ones we are quite familiar with.” An intellectual-property lawyer at the same firm told Quartz that legal costs for such cases can run into “several hundred thousand dollars.” They entail searching ”the marketplace and public record” for similar designs, meaning that “all similar products in the industry would be examined,” a massive undertaking.

For an independent designer, the costs of such a claim are almost always going to be prohibitive. On the other hand, someone with an axe to grind can easily embarrass a company online, and damage its reputation.

Judging from the sheer amount of electronic back and forth, it seems obvious that both sides would have preferred to solve the issue amicably. Instead, both have ended up frustrated. As the underdog, Asanaliev arguably has the most to lose from this already six-year-long saga. But his experience does contain one lesson for other designers: Even when you’ve run out of other options, calling someone a “thief” in public may not be the wisest option.