“Wild” is the watchword these days for health-conscious and sustainability-minded Americans when choosing which kind of salmon to eat—the assumption being that unless it is labeled as such, it is likely to have been farmed, very possibly in a cramped pen where it was pumped with antibiotics and pesticides.

But those diligent, “wild”-ordering diners are probably getting farmed salmon anyway, especially during winter. That’s according to the environmental advocacy group Oceana, which analyzed 82 samples of salmon bought in the off-season, from December to April, in restaurants and grocery stores in Chicago, New York, Washington DC, and Virginia.

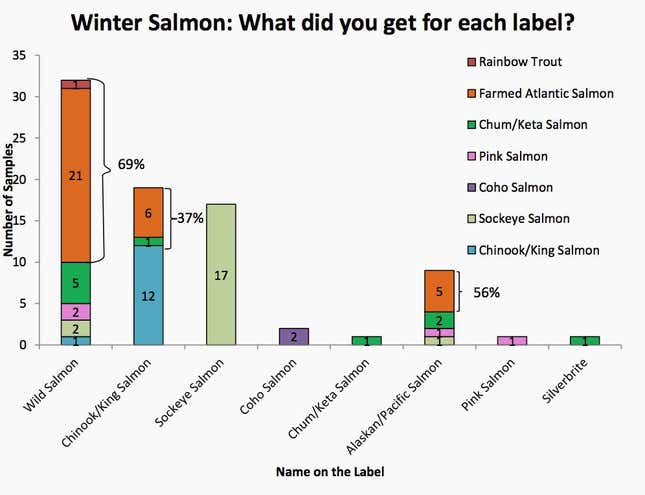

Though the sample sizes of Oceana’s analysis are too small to be representative, their findings suggest some consistent trends. More than 40% of the salmon tested was mislabeled—usually farmed salmon passed off as “wild salmon.” The bait-and-switch was more common in restaurants than in grocery stores.

And the mislabeling at the grocery store was far more likely to occur at smaller shops than at big supermarkets. Oceana’s Kimberly Warner says this is because smaller stores aren’t held to the same standards as big chain stores, which have to follow laws regarding statements about the salmon’s country of origin, its species (e.g. sockeye, coho), whether it was farmed, and how it was frozen.

Bad for overfishing

Why should consumers care? Sustainability, for one. Though we’re frequently bombarded with news about overfishing, wild salmon from American waters is among the most sustainably caught fish in the world.

Paradoxically, salmon-farming, like other types of aquaculture, can actually encourage overfishing. The famed heart-healthy omega-3 fatty acids that are so praised in wild salmon come from a lifetime of chowing down on krill. To compete on the nutrition front, farmed salmon have to be fed meal made of krill and little fish—the plundering of which can devastate ecosystems. And though this boosts farmed salmon’s nutritional value, the farmed fish tend to be much fattier than wild salmon that has to swim for its supper.

Plus, many—though not all—farmed salmon are raised in ways that pollute oceans and skew wild salmon populations. The bacteria-teeming conditions in which some salmon are farmed means they must be packed with antibiotics. And the countries where salmon is farmed have a wide range of quality controls, says Paul Greenberg, author of American Catch. Chilean growers, which he says have had more problems with fish diseases affecting the salmon supply, are more reliant on antibiotic use than Norwegian or Scottish growers, for example.

Bad for fishermen

When farmed salmon masquerades as wild, it hurts American fishermen.

Because farmed salmon is produced in much higher volumes and is generally of lower quality, it’s cheaper, undercutting the price on wild-caught salmon. Mislabeling exacerbates the price on fishermen’s prices, says Christa Hoover, executive director of the Copper River/Prince William Sound Marketing Association, which represents major salmon fishing communities in Alaska.

“If the consumer is unsure that the wild salmon in a seafood case is in fact Copper River sockeye, for instance, it is much easier to purchase a lower cost farmed salmon fillet, reducing the sales of wild salmon,” she says, “and of course reducing the demand reduces the ex-vessel price paid to fishermen.”

Thanks in part to lax demand from American consumers, the US exports about 70% of its wild salmon catch, while simultaneously importing a higher volume of salmon—most of it farmed.

How to get the salmon you’re paying for

In Oceana’s winter analysis, 21 out of 32 samples of “wild salmon” were farmed (one was rainbow trout, which can be dyed to look like salmon).

So what are diners to do? One rule of thumb, says Oceana’s Warner, is that if a menu entry ”just says ‘salmon,’ it’s pretty much always going to be farmed salmon.” And the more specific the menu or label is, the more likely it is to be accurate.

Buying salmon in season also seems like a good guideline to follow, particularly in restaurants. Knowing a bit about salmon species might help, too. Foundering chinook (a.k.a. king) salmon numbers could be why the study found a higher incidence of farmed salmon passed off as that species. On the flip side, booming Alaskan sockeye catches in the last few years make them one of the most commonly caught species in the US. This might explain why all of the labels for “sockeye salmon” that Oceana analyzed were truly sockeye.

“[I]f you have an interest in supporting well-managed American fisheries, then eating sockeye fits the bill,” advised Greenberg, the American Catch author, who warns that the country’s largest sockeye fishery, in Alaska’s Bristol Bay region, is threatened by mining development. “I’ve tended to feel that buying American sockeye puts a few more dollars in the pockets of those fishermen who are trying to gain lasting protection for the Bristol Bay sockeye spawning grounds,” he says.

Greenberg tends to have sockeye at home, though he orders it on occasion when it appears on restaurant menus.

“If you do order it, ask for it rare,” he recommends. “I cook it at home under a hot broiler for no more than three minutes.”