America catches some of the world’s best salmon but eats some of the worst

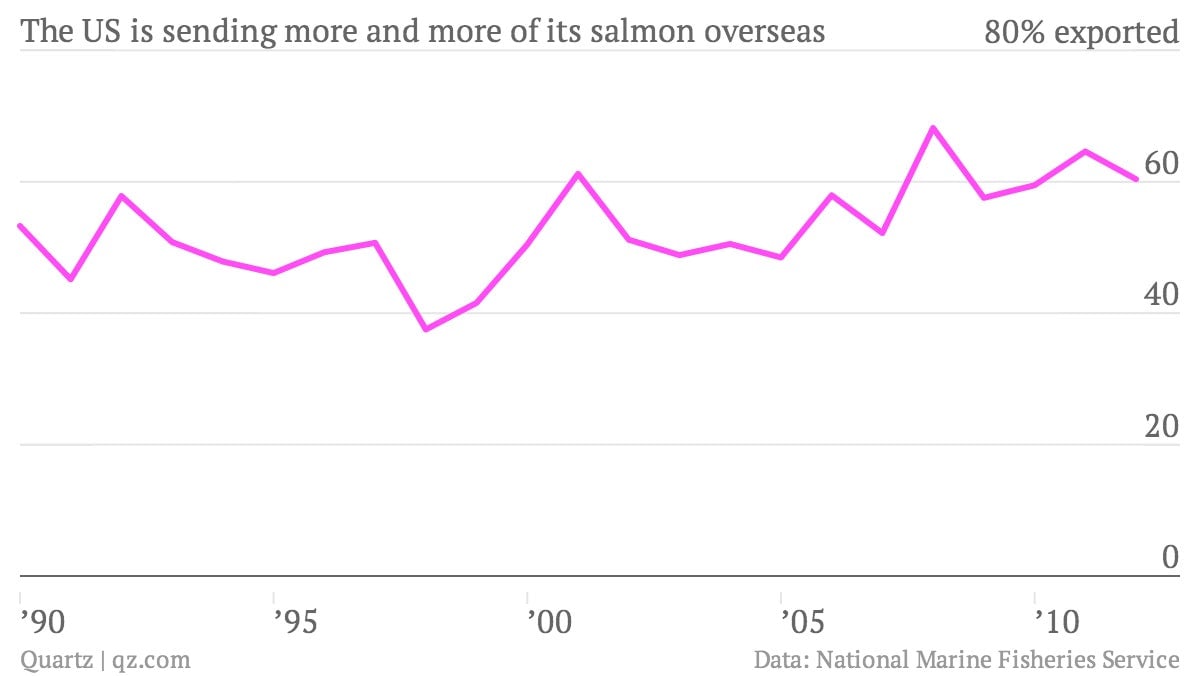

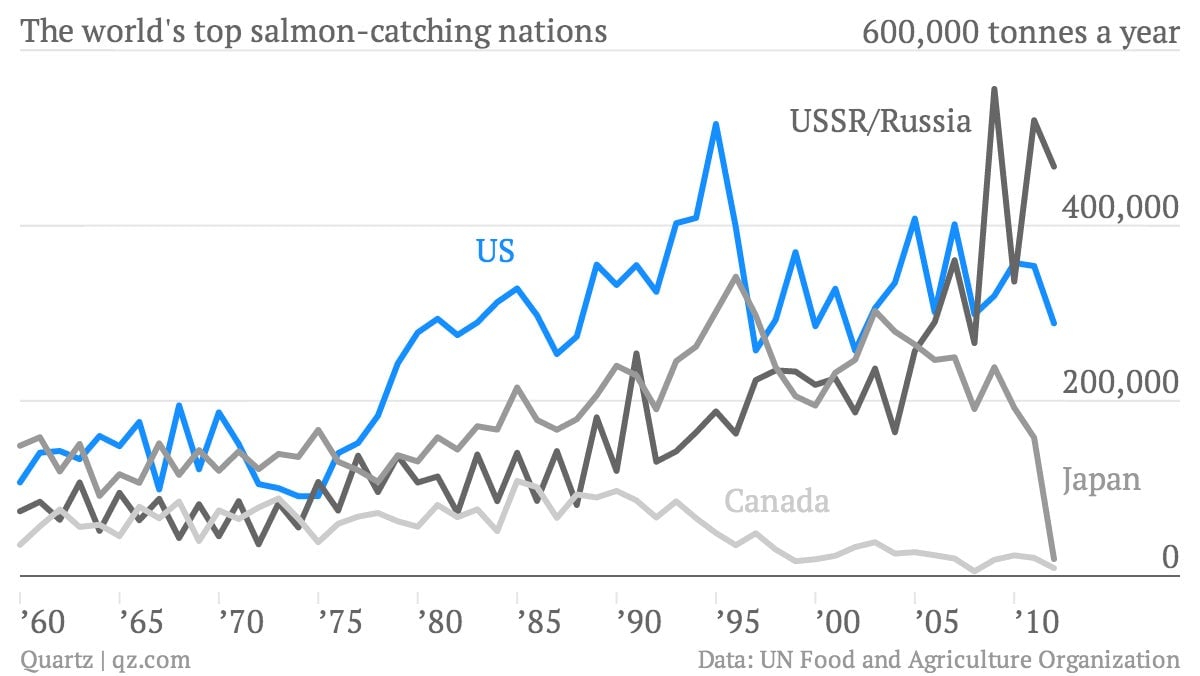

The US is a salmon-catching powerhouse. Nearly one-third of the world’s wild salmon supply comes from US nets. Even when you take into account farmed salmon, US fishermen still bring around one-tenth of the total supply of salmon to the market. But more than half of America’s salmon catch is going overseas:

The US is a salmon-catching powerhouse. Nearly one-third of the world’s wild salmon supply comes from US nets. Even when you take into account farmed salmon, US fishermen still bring around one-tenth of the total supply of salmon to the market. But more than half of America’s salmon catch is going overseas:

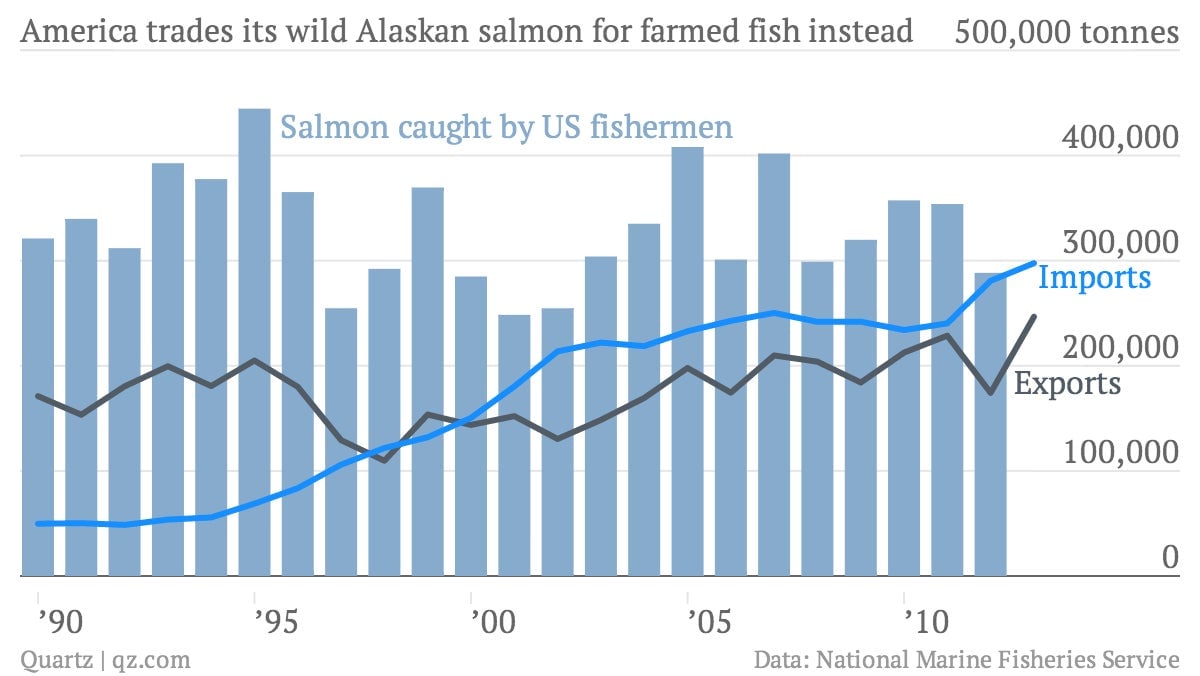

It’s not that Americans aren’t eating salmon. They are—just not their own. Two-thirds of the salmon eaten by US consumers is imported—mostly from farms in Chile, Canada and Norway and from processing factories in China. More than just a quirk of taste, this habit of snubbing domestic salmon in favor of foreign farmed fish exemplifies a more disquieting trend for US industry, argues journalist Paul Greenberg in his book American Catch: The Fight for Our Local Seafood (purchase required). It’s the result of an American seafood ignorance that could threaten both the country’s long-term status as a fishing powerhouse and its secure supply of nutritious protein.

The network of freshwater streams and coastal waters of the US’s Pacific Northwest is one of the country’s most bounteous natural resources, supplying many hundreds of millions pounds a year of salmon, some of the most nutritious wild protein in the world. In the early 1900s, species including the king and coho salmon abounded in Oregon, Washington, and northern California.

But a dam-construction bender during the New Deal in the 1930s and 40s destroyed the spawning habitats for millions of salmon. The salmon populations of the Snake and Columbia River systems in particular were decimated, leaving Alaska as the last major US source of wild salmon. The fine web of ponds and streams that form southwest Alaska’s Bristol Bay is the biggest remaining sockeye salmon run on the planet.

So why are Alaskan fishermen sending more than half of their catch overseas?

Part of it has to do with processing. Since many Americans don’t like picking out bones and are squeamish about eating something with its head still on, they need their seafood broken down and packaged before it hits the frozen section of the grocery store. But deboning and filleting fish is a lot harder to mechanize than, say, carving up a chicken or a hog. So the US has outsourced the vast majority of its processing capacity to places like China, where labor is relatively cheap.

For a long time, when Alaskan fishermen sold their salmon to processing plants in China, after it was defrosted, filleted, deboned, and refrozen, it would be shipped back to the US. Nowadays, a rising share of American-caught salmon is simply staying in Asia, says Greenberg, thanks to China’s surging wealth and Japan’s dwindling fish supply.

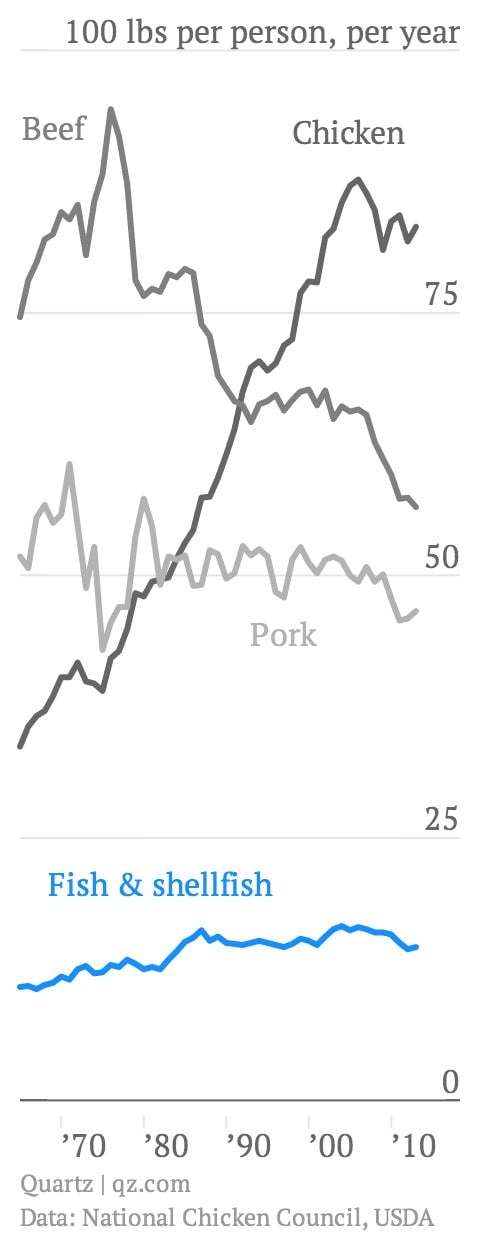

But tepid US demand for salmon has been a huge factor too. “Our coastal populations once ate a lot more fish. And the interior would have eaten a lot of freshwater fish that was instead quickly eradicated due to agriculture,” says Greenberg. “There was a mandate in this country to boost the production of land food—we made that a national priority. And once you lose the taste for fish, it’s hard to get it back.”

As a result of that cultural and economic emphasis on “land food,” Americans now eat a little less than half of the global annual average seafood consumption—and consume 13 times as much red meat and poultry as they do seafood.

The health benefits of seafood are finally starting to dawn on Americans. Salmon is an excellent example; it’s packed with omega-3 fatty acids that are thought to promote heart health. Sockeye salmon is rich in antioxidants as well. But instead of demanding their own Pacific salmon, Americans are mostly eating the blander-tasting, farmed Atlantic variety imported from countries like Norway and Chile, or other farmed fish from China.

This isn’t necessarily healthier. Some of these salmon come from farms that aren’t always the cleanest. For example, fish (though not salmon) from Chinese farms has been found to contain potentially carcinogenic chemicals. And as Greenberg notes, less than 2% of imported fish are directly inspected by the US Food and Drug Administration. What’s more, the US’s lax labeling laws mean that by the time salmon hits American dinner tables, it’s often hard to tell where it came from. (For comparison, Japan requires labels to indicate both where the fish was caught and where it was processed.)

Neither are salmon farms all that ecologically sound (paywall). Scientists worry the introduction of Atlantic salmon farms on the Pacific coast could warp the wild stock’s gene pool and spread diseases against which wild Pacific salmon haven’t developed immunity. The millions of salmon that escape each year are effectively invasive species that threaten to skew local ecosystems. Many farms pollute waterways with excess fish excrement and uneaten feed, which can contribute to algal blooms and other ecological menaces. “Is that something consumers should be underwriting?” Greenberg says.

On the other hand, American consumers can be confident that when they do consume Alaskan wild salmon, it’s caught by what Greenberg calls one of the best-managed fisheries in the world, and from waters kept clean by environmental standards.

In that sense, eating American fish is important not just for the country’s salmon supply; it also creates an economic incentive to keep streams and oceans clean, Greenberg argues. Just as America’s reliance on land-raised meat once did, sourcing fish from overseas farms makes it easy for American consumers to ignore industrial threats to US fishing resources, such as the gold and copper mine proposed in southwestern Alaska, which many believe will risk poisoning the Bristol Bay sockeye run if the US government allows construction to proceed.

What can the US do about all this? Rebuilding America’s seafood-processing industry is a good place to start, says Greenberg. The sheer scale of America’s catch implies that there would be plenty of work for US-based processing factories to do. As for the labor cost issue, the steady rise of China’s labor costs since processing jobs left American shores means US factories wouldn’t face the competitive disadvantage they once might have. And keeping fish in the US makes it easier for it to find its way to American—and not Asian—plates.

But it ultimately falls to American consumers to tip the balance, says Greenberg. “We should stay the course as far as what we’re catching—we have good rules, we have good laws,” he says. “[But] we should eat the fish that we catch instead of trading it away.”