By appearances, OPEC has the tell-tale signs of an aging prizefighter. It still technically possesses a knockout punch, but it’s unable to land one against younger, more agile opponents, amid doubts as to whether it has the legs to go the distance.

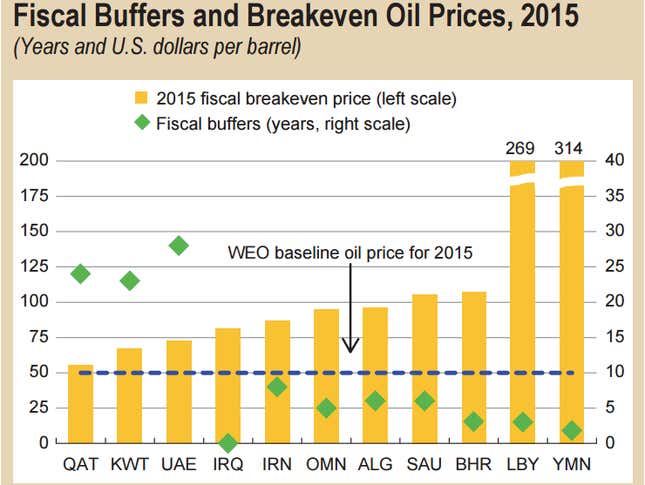

The last few days have bolstered this view. As OPEC continues its now-17-month price war against upstart US shale oil, global oil prices fell under $45 a barrel last week, breaking through a threshold that had held for months. Alarmingly if you happen to be an OPEC member, that’s far below the price needed by almost all of them to balance their state budgets (see chart, right). In addition, unlike what has happened after previous flirtations with $45 oil since August, traders didn’t look for a quick rebound. Instead, they continued to sell into the drop, thus appearing to be scouting for a new, lower band for the global Brent benchmark.

Against all this, US shale is still more or less holding up. US oil production is off its 9.6 million-barrel-a-day peak from April, but was still delivering about 9.1 million barrels a day in October, according to the US Energy Information Administration (EIA). The EIA thinks that US production will drop to 8.8 million barrels a day next year, of which about 4 million would be shale oil—hardly a death blow.

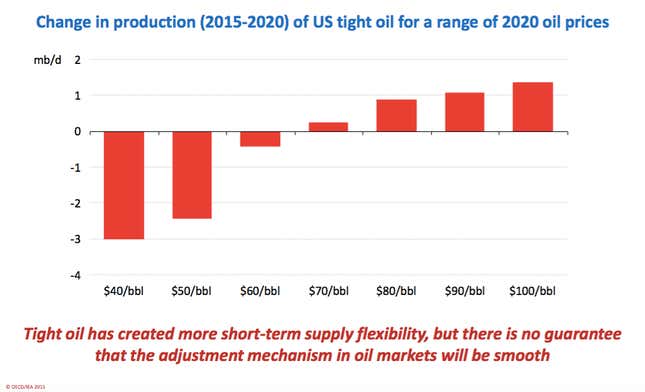

Yet things could get worse on the US oil patch, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). The IEA’s base case is for oil to rise to a far more profitable $80 a barrel by the end of the decade. But if shale defies the EIA forecast and is able to sustain production—and if OPEC continues its Saudi-led, no-holds-barred output—prices could stay at about $50 a barrel through the end of the decade, according to a Nov. 10 presentation by IEA director Fatih Birol.

In that case, though, US shale production ultimately would buckle, Birol says—plummeting by a projected 2.2 million barrels a day (see chart below).

So who is on the ropes—OPEC or shale?

The thing is, for the last 17 months, oil has gone its own way and listened to no one—not on price, not on supply, not on the cost of drilling, and, of particular relevance, not on how long US shale could withstand OPEC’s brutal price war.

This fact seems to nag at the ordinarily ultra-confident investment bank set—their debate on who is truly controlling the market and where prices are headed continues to rage, but none can be confident they are right.

This is plain in a spate of roundabout notes to their clients this week, messages that can collectively be summed up pretty much as: Run for the hills. That is, the war, and relatively low prices, seems likely to persist for some time.

“We aren’t going to pretend that the data or commentary is in any way bullish right now, but we nevertheless feel that the market is correcting, based on quarterly [earnings per share] season that has shown just how unsustainable less-than-$50 a barrel oil is,” Paul Sankey, an analyst with Wolfe Research, wrote in a Nov. 12 note.

Earlier the same day, Citi’s Ed Morse said in a note that low prices are simply a reflection of an oversupply of oil, in addition to “increasingly fraught competition” for market share among OPEC members, not to mention between them and Russia. “Shale production, though declining, is still quite resilient,” he aded.

Of course, oil traders themselves—profiting from the OPEC-shale war and the gyrations of oil prices whether they happen to be high or low—will venture nowhere near the hills. They will remain in the game and attempt either to become filthy rich, or richer.