Interns in China are the latest group to complain about Uber’s labor practices.

The company’s lean business model in China, former interns and a manager claim, relies on the exploitation of huge numbers of barely paid students and recent graduates, who toil up to 15 hours a day for as little as $5 a shift, and sometimes are paid nothing. These interns are tasked with signing up hundreds of drivers in one day, they allege, in addition to other tasks performed by employees in other countries.

“It’s normal for internships to be demanding, but I’ve never experienced these sort of long hours, and repetitive, cumbersome types of work” Li Yifan, a former operations coordinator at Uber Guangzhou, told Quartz on the phone. Li posted an open letter (link in Chinese) on December 4 on Sina Weibo detailing his three-month tenure at Uber, which alleges the company’s reliance on underpaid interns amounts to “discrimination” against China.

Although an Uber company spokesman declined to answer “item by item” questions about the accusations, Uber generally denied mistreatment of interns, noting it offers “a competitive package” to interns and complies “with local laws and regulation.” Under Chinese law, only students can be interns, and contracts and pay are not required until they graduate, when they are defined as employees.

Uber faces driver unionization in Seattle and a class action suit in California over below minimum wage pay and the company’s refusal to pay benefits or expenses to its contract worker drivers. The allegations raise questions about how dependent the $45 billion company may be on cheap, informal labor for its expansion in China, at a time when competition from Didi Kuaidi, a rival that’s nabbing seven times as many daily bookings as Uber, is heating up.

Uber China’s 200 employees

Li Yifan, the former Uber employee, claimed in his open letter that Uber Guangzhou relied on interns to sign up drivers and answer emails from passengers and customers—tasks handled by full-time employees, or outsourced staff, in other locations.

The office was tasked with signing up as many as 50,000 new drivers in one week, he alleges, or 7,000 a day, and interns worked more than 10 hours a day to meet individual quotas. Each intern was required to personally register a minimum of 100 drivers a day, he said, though some signed up as many as 400, working 15 hours. At the same time, they had to answer hundreds of emails from drivers and passengers throughout the day.

Li said Guangzhou added so many many interns to meet the quotas that they outnumbered full-time employees 7 to 1. Uber paid most of them 30 to 100 yuan (about $5 to $15) per day, depending on a “monthly evaluation” given by superiors.

Outside of China, “a city maybe has 20 people working in operations, and five or six operations coordinators, and very few interns. In China, the situation is totally the opposite. This is definitely a form of discrimination,” he writes.

Uber would not provide any specifics about its intern to employee ratio in China. But the company does have a disproportionately small number of employees compared to rival Didi. Uber claims to only have 200 employees in China (paywall), versus Didi’s 4,000—making Uber’s employees seem a lot more efficient when judged by rides per employee.

Didi would not provide its employee to intern ratio.

Not an isolated case

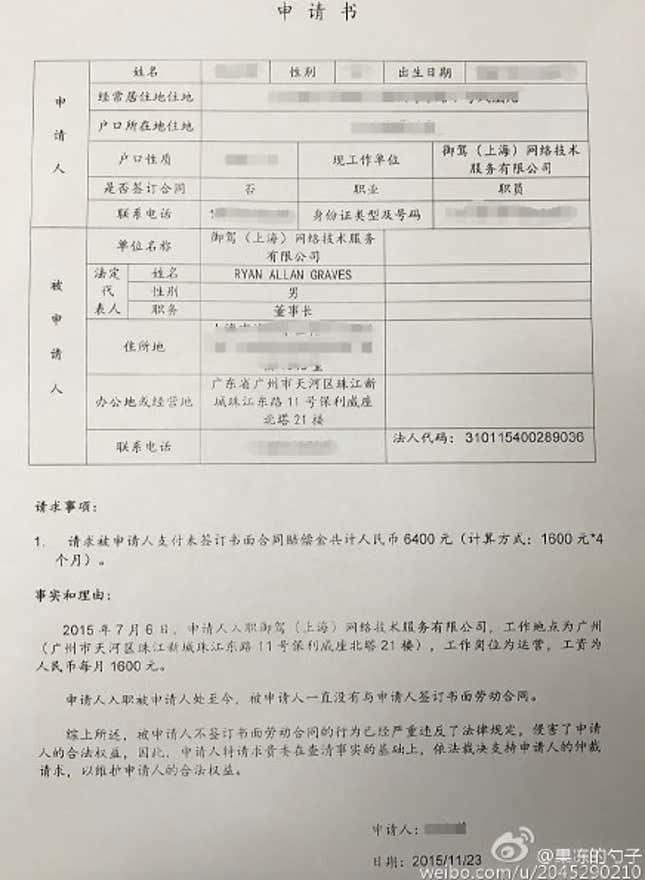

Uber interns have expressed similar complaints. Li posted a lawsuit (link in Chinese) that one intern who worked for him filed with the Guangzhou Municipal, Human Resources and Social Security Bureau, saying the company never paid the 6,400 yuan it owed, an average intern’s wages over four months.

Another former Uber intern, Ma Yingkai, posted a message on Weibo (link in Chinese) making similar claims. After joining Uber in May as an intern in Tianjin when he was a student, Ma claims that he and a few colleagues were tasked with fielding emails and activating accounts for the city’s rapidly expanding pool of drivers. A manager told his team to work from 6AM to 8PM, but after a few months, Ma said he and his teammates received a text message from a superior informing them they would be fired for accessing Uber’s “database during non-work hours.” Ma claims he and his teammates were just doing what they were asked to do.

Ma tells Quartz that interns in the Tianjin office outnumbered formal employees 10 to 1, and that he only met a formal employee in person once during his month with the company.

Meanwhile, a former Uber intern in Shanghai told Quartz on the condition of anonymity that the company did not offer her or her colleagues contracts for their internships, and said the working conditions described in the letters were “not far from the truth.”

“Shanghai wasn’t as strict, I think. But it’s true that the work atmosphere is not good,” she told Quartz. The ratio of interns to employees at the “Diver Support Division” where she worked was about 10 or 15 to 1, she said.

Fierce rivalry

The complaints from Uber’s ex-interns and employee come as competition between Uber and Didi Kuaidi has become cutthroat. The two companies are fighting bitterly for customers, drivers, funding, media attention, and talent. Tencent, a Didi investor, banned Uber from marketing on WeChat, the most popular social network in China. Uber, meanwhile, stole a major investor (paywall) from Didi during a recent funding round.

Uber and Didi are both facing pressure from the Chinese government, as authorities ponder the legal future of ride-hailing. While neither firm has suffered a nationwide crackdown, there’s evidence that the government is siding with Didi, which scored an investment from China’s sovereign wealth fund. Uber’s CEO, meanwhile, was conspicuously absent from a China-US tech summit photo with Chinese president Xi Jinping.

Labor exploitation is not unusual in China, at local internet companies or foreign firms, Prof. Teng Bingsheng, who studies Uber and other Chinese tech companies at the Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business in Beijing, told Quartz.

“It’s common that employees, including interns, of Chinese internet firms work very long hours, in order to get ahead of the competition,” he tells Quartz. “In the past [multinational corporations] in China have been trying to avoid abusive use of labor. However, when competition gets tougher, it certainly becomes a possible corner to cut,” says Prof. Teng.

The public airing of these allegations may be motivated by the rivalry between the two companies itself. After all, Li is now working for an Uber competitor, who he would not name, and he claims Uber is suing him for violating a non-compete clause. Executives or interns choosing between the two companies in China may be swayed by public reports of Uber’s business practices.

But that doesn’t explain away the accusation that Uber is overly dependent on cheap or unpaid intern labor in China. “When we talk about Uber, they portray themselves as heroes,” Li wrote on Weibo. “Two people start a city, twenty people can help manage 20,000 daily bookings…But is this really true?”

Zheping Huang contributed reporting.