With its dizzying array of manufacturing facilities, China’s southern Guangdong province is nicknamed “the world’s factory.” But key to earning that title has been a seemingly endless supply of workers willing to work for very little, and in recent years labor strikes demanding better pay and treatment have been steadily rising. In response, the government is cracking down on the workers’ key allies: labor rights NGOs.

Labor NGOs have a special importance in China because the country’s only legal trade union—the All-China Federation of Trade Unions—is controlled by the government and often friendlier to employers than to workers.

The latest crackdown incident is what appears to be a smear campaign against Zeng Feiyang, leader of the Guangzhou-based Panyu Migrant Workers Center and one of the nation’s most outspoken activists. According to a Dec. 22 article (link in Chinese) by state mouthpiece Xinhua, Zeng intercepted and embezzled payments from factory employers meant for workers after strikes he helped organize.

Starting at the end of last year, Zeng helped coordinate a series of successful strikes at Guangzhou’s Lide shoe factory, where workers had complained of unpaid overtime and inadequate pensions and holidays. As Reuters reported, Zeng faced harassment, and the police declined to investigate when someone doused his car with gasoline. ”If they put me in prison, I will have no regrets,” he said at the time.

His center, one of about 30 labor right groups in southern China, holds workshops, shows factory employees how to organize strikes, and provides them with legal aid. A troubling aspect of the center, according to the Dec. 23 Xinhua report, is that it receives funding from “overseas organizations” and offers them reports on China’s labor movement in return, plus it has close contacts with foreign embassies in China.

According to the report, seven labor activists including Zeng were detained and investigated by police. The activists came from at least four local labor NGOs, rights groups said. One detainee was charged with “embezzlement,” and three others with “inciting crowds to disrupt public order”—one of the many absurdly broad crimes that are arguably used as political tools to suppress civil rights movements.

This latest incident follows the Dec. 3 arrests of more than 20 labor activists in Guangdong.

Xinhua’s report also dug into the personal life of Zeng, who is married. Citing evidence from police investigations, it reported he had affairs with eight women, and often tries to persuade female workers and volunteers to have sex with him. It went on:

According to the police, Zeng Feiyang is keen on online “nude chats,” prostitution, and sending a large number of sex videos and vulgar text messages to different women. Zeng Feiyang had joined a nude chat QQ group, but was kicked out because he was “too dirty.” Police have also seized a large number of pornographic materials at Zeng Feiyang’s home.

Xinhua also attacked the foreign media, saying it had “maliciously hyped” the Lide strikes and directed the blame toward the local government.

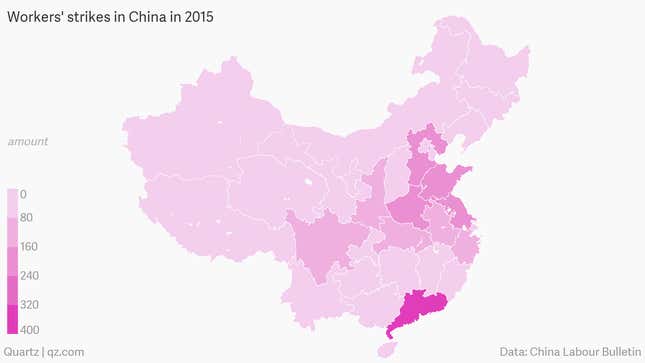

If Beijing seems overly sensitive on the labor issue, it isn’t without reason. On top of a slowing economy, as labor costs in China keep rising many factories are moving to cheaper locations, such as Vietnam. Meanwhile the number of protests and strikes in Guangdong doubled from 23 in July to 56 in November, according to the Hong Kong-based advocacy group China Labour Bulletin. Overall, Guangdong has had nearly 400 strikes this year—the most across the country:

In May Beijing drafted a new foreign NGO management law, precluding Chinese groups from taking any funding from unregistered foreign partners—including those based in Hong Kong and Macau—and conducting any activities on the behalf of such partners.

Of course, China’s government tightly monitors and controls most types of activism that may spark public challenges or instability. Five feminist activists were arrested in March after planning to distribute promotional materials against sexual harassment. And in July more than 100 lawyers and human rights activists and their relatives were detained across the country.