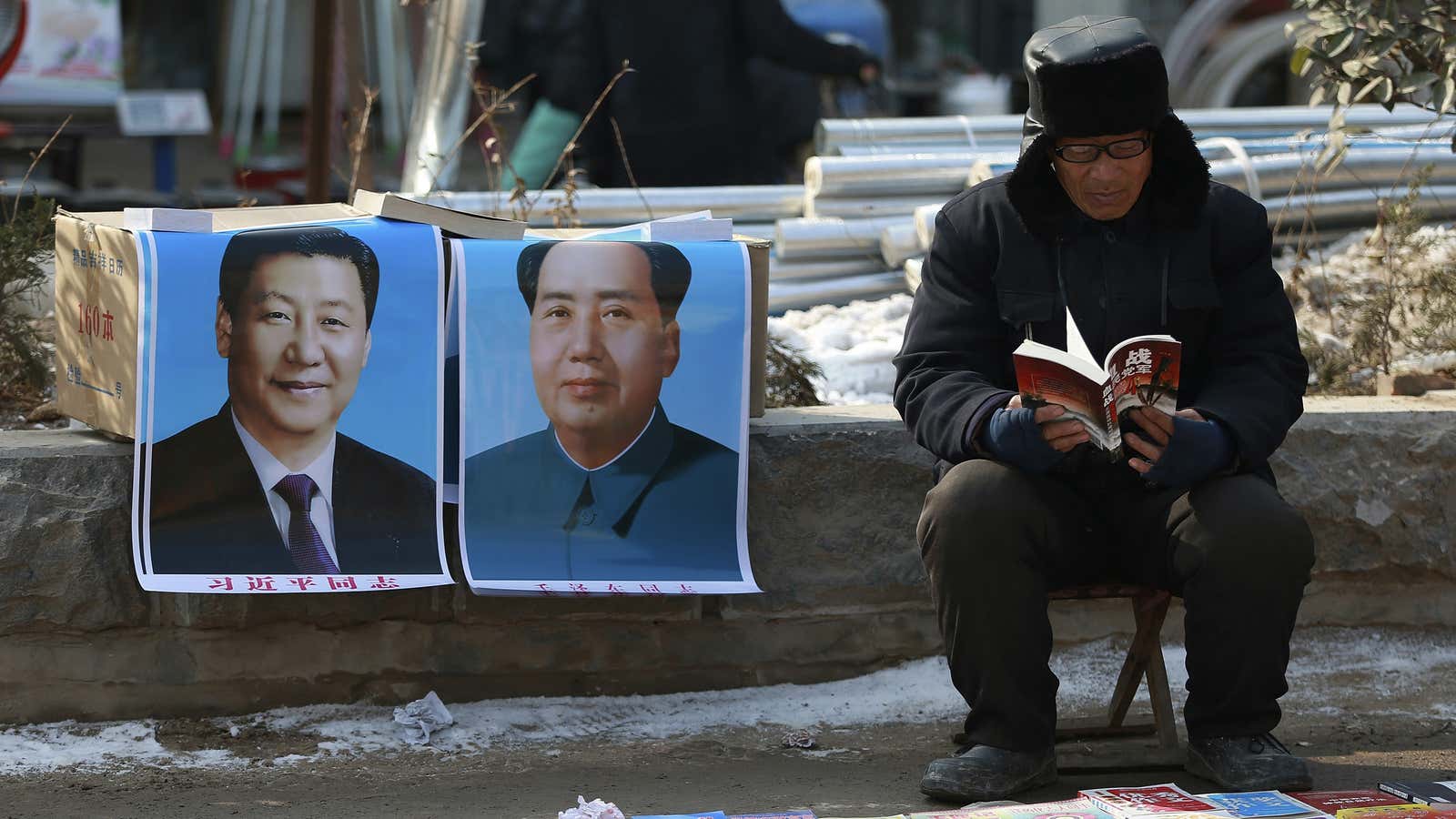

The latest directive from China’s top leader, Xi Jinping, highlights the strength of his obsession with Mao-era ideology.

On Thursday (Feb. 25), Xi ordered all Communist Party officials to read an essay by Mao Zedong, and to learn “the art of leadership” (link in Chinese) described in it. The order was issued to Party committees in the army, state-owned enterprises, universities, and government bureaus, and was widely reported by state media including Xinhua news agency and People’s Daily.

It is not common for a top Chinese leader to give a public order to his party members to learn from Mao. Chairman Mao, the founding father of the People’s Republic China, ruled China for more than 30 years, and is still revered by many citizens. But his last decade was marked by chaos, thanks to a revolutionary campaign that spread violence and persecution nationwide, and he has rarely been held up as an example of great leadership since his death.

Xi’s revival of Mao’s ideologies has already raised concerns from many China watchers, and the descendants of former Party leaders.

Mao’s essay, titled Methods of work of Party committee (pdf, page 377), was written in March of 1949, on the eve of the founding of Communist China. In it, Mao uses a colloquial tone to describe 12 points about forming a sound Party leadership.

The most important of these 12 points today is the very first, that discusses how party leaders should be coordinated, and work together, according to one veteran journalist who now studies the Party’s statements. Here it is in full:

The secretary of a Party committee must be good at being a “squad leader.”A Party committee has ten to twenty members; it is like a squad in the army, and the secretary is like the “squad leader.”

It is indeed not easy to lead this squad well. Each bureau or sub-bureau of the Central Committee now leads a vast area and shoulders very heavy responsibilities. To lead means not only to decide general and specific policies but also to devise correct methods of work. Even with correct general and specific policies, troubles may still arise if methods of work are neglected. To fulfill its task of exercising leadership, a Party committee must rely on its “squad members” and enable them to play their parts to the full. To be a good “squad leader”, the secretary should study hard and investigate thoroughly.

A secretary or deputy secretary will find it difficult to direct his “squad” well if he does not take care to do propaganda and organizational work among his own “squad members”, is not good at handling his relations with committee members or does not study how to run meetings successfully. If the “squad members” do not march in step, they can never expect to lead tens of millions of people in fighting and construction.

Of course, the relation between the secretary and the committee members is one in which the minority must obey the majority, so it is different from the relation between a squad leader and his men. Here we speak only by way of analogy.

Mao’s remaining 11 points are:

- Place problems on the table. “Do not talk behind people’s backs,” he wrote.

- “Exchange information.” Mao criticized Party members who don’t have a “common language” because they don’t talk to each other.

- Ask your subordinates about matters you don’t understand or don’t know, and do not lightly express your approval or disapproval. “Be a pupil before you become a teacher,” Mao said. “Learn from the cadres at the lower levels before you issue orders.”

- Learn to “play the piano.” This is an analogy. Mao warned the Party shouldn’t neglect other work while focusing on its primary tasks, just as “all ten fingers are in motion” when playing the piano.

- “Grasp firmly.” This is an emphasis on commitment. A Party committee should not only “grasp” its main tasks, but also “grasp firmly” its main tasks, Mao wrote.

- “Have a head for figures.” These include “the basic statistics, the main percentages and the quantitative limits.” Mao criticized Party officials for not having a sense for statistics. “They have no ‘figures’ in their heads and as a result cannot help making mistakes.”

- “Notice to Reassure the Public.” Plan ahead, and completely, for Party meetings. “Don’t call a meeting in a hurry if the preparations are not completed,” he wrote.

- “Fewer and better troops and simpler administration.” This is an analogy. Meetings and speeches should not be too long.

- Pay attention to uniting and working with comrades who differ with you. Mao stressed officials should unite “those who hold different views,” even “outside the Party.” He wrote “There are some among us who have made very serious mistakes; we should not be prejudiced against them but should be ready to work with them.”

- Guard against arrogance. Mao banned celebrations of Party leader’s birthdays and naming streets and enterprises after Party leaders. He praised plain living and hard work, and warned against “flattery and exaggerated praise.”

- Draw two lines of distinction. Distinguish “between revolution and counter-revolution,” Mao wrote, and between headquarters of the Communist Party and that of the overthrown Kuomintang government. Bureaucracy inside the Party doesn’t mean “nothing is right” inside the Party, as it is still part of the revolution. On this basis, a second line should be drawn “between achievements and shortcomings,” he wrote.

Some of Mao’s points seem very topical today—he could be describing the Chinese government’s sketchy “official” data and failure to control the image of China. But if the “squad leader,” point is, in fact, the most important, then Xi’s main goal with this reading assignment may be further promotion of a one-man dictatorship. The last point, about drawing a line “between revolution and counter-revolution,” could also be interpreted as his willingness to clamp down on dissidents and those who challenge the Party today.

Echoing Mao, Xi initiated a sweeping anti-graft campaign since he took control in November of 2012, and even made a landmark speech encouraging socialist artwork. He has also paid tribute to Mao by raising terms used only in the Mao era, and summoning the army’s loyalty to him at the same place where Mao did.