Mexico City, Mexico

It’s a Tuesday morning in the Xochimilco neighborhood of southern Mexico City, a lively world heritage site known for its network of canals and floating gardens. On the weekends, the space is clogged with colorful party boats carrying drunken revelers and traveling mariachi bands but today, the murky green waterways are empty and eerily still. A lone vessel glides by, filled with Greenpeace volunteers wearing hazmat suits and ominous expressions.

Architect Elias Cattan, president of the architecture firm Taller 13, leans over the edge of the boat, dipping a small glass jar into the water. He seals it with a twist-on cap and examines the sample; tiny unidentifiable critters squirm amidst the sludgy liquid and neon algae disperses like flakes inside a snow globe. A few pieces of garbage sink to the bottom. “This is perfect,” Cattan tells Quartz. “The dirtier, the better.”

On the day Quartz visits, Cattan and his small army of environmentalists are collecting jars of dirty water from nearly a dozen different sources throughout the Mexico City metropolitan area. Eventually, Cattan’s team amassed more than 15,000 of these jars, which now form the structural backbone of a large-scale art installation.

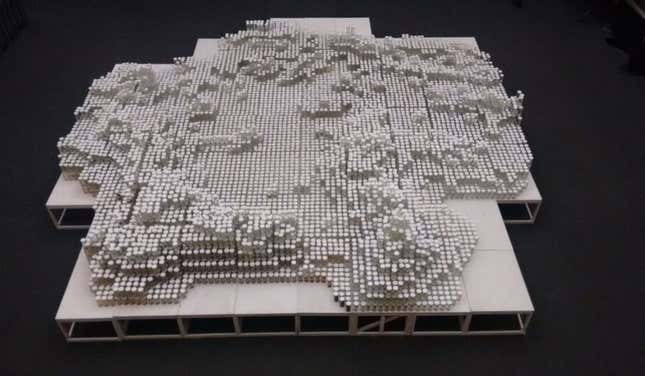

That sculpture, a commentary on the disastrous history of Mexico City’s water management system, is currently on display at the Interactive Museum of Economics as part of the UN’s World Water Day on Mar. 22 and Greenpeace’s “Operacion Ciudad” campaign. The 15,000 jars, filled with dirty water from nearly a dozen sources, are stacked into the shape of a miniature topographical map of the city, telling the story of the Mexican capital’s complicated relationship with water.

“Mexico City’s water system goes against its own functional essence,” Cattan tells Quartz. “The city is dehydrating itself. We’re mixing our water with poisonous waste and then pumping it out through a complex network of pipes. Just like what happens when a human is dehydrated, Mexico City has diarrhea.”

Cattan explains that prior to the late 1400s, when the Spanish colonization of Mexico began, the country’s indigenous communities engaged more harmoniously with life’s essential liquid. The entire city was designed along a canal system like Xochimilco’s. Water flowed with the force of gravity down from dense, biodiverse forests, and it filtered naturally through wetlands before residents engaged with it passively. Rainwater collected in lakes during the annual downpours, where it was stored for use during the drier months.

Then the Spanish arrived. “Early colonialists came from arid climates, so they didn’t know what to do with all the water,” Cattan says. “Rather than living with it, they decided to ‘conquer’ it.”

Approximately 500 years of total water annihilation followed, resulting in a current system that is a convoluted, leaky mess. Today water is diverted backwards and sideways and against its natural flow, in the process contaminating it with pollution and draining some communities dry while saturating others in waste and filth.

Nearly a quarter of the water supply escapes through faulty pipelines. Indigenous lands in the rural regions of the metropolitan area are being decimated. Sewage is used to irrigate vegetables that are then shipped back into the city’s food supply. The most marginalized areas can go for more than a month with empty taps, and when they do finally receive running water again, it comes out smelly and yellow-tinted. Projects aimed at upgrading and maintaining the existing infrastructure are bloated with political kickbacks. According to researchers from the National Autonomous University of Mexico, Mexico City has more cases of water-related illnesses than any other major city in the world.

A recent Guardian investigation traced Mexico City’s boondoggled water system from the source to the sewer in an attempt to understand how such a water-rich area faces such serious problems. “This most fundamental of elements flows through a system that grows more complex and more fraught by the day,” reporter Jonathan Watts wrote. “Discharging a resource that falls freely from the heavens and replacing it with exactly the same H2O from far away is expensive, inefficient, energy intensive and ultimately inadequate for the population’s needs.”

But it doesn’t have to be this way. In a mega-metropolis with a deep history of corrupt leaders and state-sanctioned misinformation, Cattan believes awareness is the first step. That’s why he’s part of a growing movement of environmental scientists, activists, designers and engineers determined to redesign Mexico City’s water supply management while educating its 9 million residents in the process.

Campaigns are already underway to deepen and refill Lake Chalco, which was paved over years ago but which advocates say would have the capacity to meet the water needs of 1.5 million people. A handful of schools in the distressed Iztapalapa neighborhood have experimented with capturing and repurposing rainwater that falls on their roofs.

Marco Alfredo, president of the Mexican Association of Hydro-Engineers, is in the process of drafting a “water declaration”—a proposal that, if enacted, would completely overhaul the current system. He’ll submit his plans to president Enrique Peña Nieto before the end of this year, according to the Guardian.

“This is not an engineering problem: we have the expertise and the experience. It is also not a problem of economics: we have the financial resources to do what needs to be done,” Alfredo told the Guardian. “It’s a problem of governance.”

In Cattan’s vision of a fully regenerative system, wastewater and sewage is treated close to the source and then consumed locally. A “constellation of green infrastructure,” rife with wetlands that would act as natural filters, would be introduced into densely populated urban areas.

La Piedad, a long-since-drained river that now serves as a water pipeline underneath one of the city’s busiest highways, would be the perfect test case, Cattan said. His architecture firm has already drawn up the blueprints.

“We’re used to have one of the most pristine and unique water systems on earth,” he said. “The damage we have done is reversible.”

Visit Mexico City’s Interactive Museum of Economics before March 27 to see Cattan’s installation, ¡Aguas!, in action.