George Osborne, Britain’s finance chief, will present his fourth budget to parliament today. And according to the Financial Times he’s expected, yet again, to admit he won’t meet the government’s own targets for cutting the budget (paywall).

The Conservative-led coalition government originally promised that—thanks to the austerity budgets it put in place upon gaining power in 2010—the UK’s debt-to-GDP ratio would start to fall by 2015-16. It wasn’t to be. As many economists had warned, those cuts dragged on growth. And the dragging growth weighed on tax revenues. Lower revenues meant the government had to borrow more in the bond markets to keep the lights on.

The result? Back in December Osborne was forced to admit that he’d miss the 2015-16 target. That hurt, as did Moody’s decision to strip Britain’s Aaa rating back February. (Cameron & Co. had long justified their austerity push, in part, on preserving the cherished credit rating.)

Now the FT reports that Osborne is prepared to concede that it will take even longer for Britain’s debt load to start to shrink. It might have to wait until 2017-18.

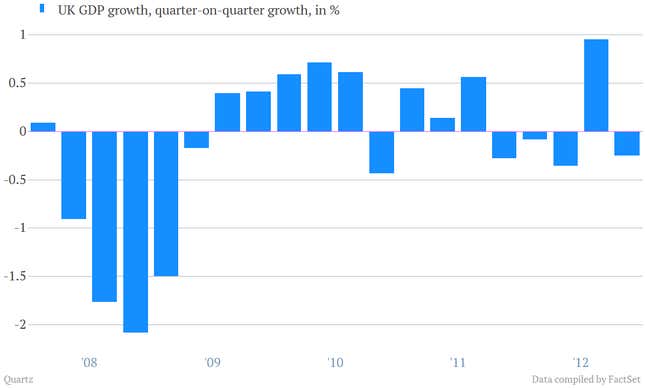

That hurts politically. But the more important points are economic. And thanks, in part, to the British government’s relentless focus on austerity, the UK now finds itself tottering on the brink of a triple-dip recession (although, in fairness, not a particularly deep one.) Take a look:

What is to be done? Prime minister David Cameron seems unlikely to shift towards a more free-spending budget stance any time soon. But rather than admit that austerity push isn’t working, it looks like Cameron’s government has started angling for a backdoor bailout of his policies from the Bank of England.

Cameron’s budget chief—Osborne—is widely expected to open the door to a easier monetary policy from the BoE as part of the budgetary proceedings, perhaps announcing a formal review of the Bank of England’s remit. Unlike the US Federal Reserve, which has a dual mandate to generate economic growth while keeping inflation down, the BoE, like many central banks, is only tasked with worrying about inflation. And with UK inflation persistently above its target, that’s left little room for the bank to pump more cash into the economy to try to jumpstart growth.

Perhaps making it easier for the Bank of England to shore up growth would be helpful (though the bank’s incoming governor, the former Bank of Canada chief Mark Carney, seems to think that he’ll have enough flexibility). Some think Osborne could have the bank target a different, more tolerant measure of inflation.

But playing switcheroo with inflation measures seems more fitted to emerging markets than the UK. And with the British currency already looking weak, an abrupt change could send the pound tumbling and inflation shooting even higher. Can you say “stagflation?”

But more importantly, such sideshows represent a less-than-subtle effort by the Cameron government to shirk its own responsibilities to help support growth. Even staunch supporters of the Cameron government have to be thinking, “Really, is this all they’ve got?”