You may not always like her aesthetic, her candor or the politics of her clients, but Zaha Hadid, the star architect who died suddenly in Miami on March 31, has left a dark hole in the world of architecture.

An inimitable mind, Hadid often proposed dazzling “swoopy” avant-garde structures, earning the nickname the “Queen of the Curve.” Her singular stardom broke through the male-dominated profession’s stereotypes of architectural career paths for women, Arabs, emigres or anyone who has ever felt like a square peg in a round hole. When she passed away at 65, Hadid was a rarity, a celebrity, and an anointed Dame.

Hadid established herself by winning high-profile cultural commissions and was bolstered by architecture honors like her induction into the Order of the British Empire by Queen Elizabeth in 2012. She went by ”Zaha,” enjoying first-name-only celebrity brand name status, even beyond design circles.

Brands and celebrities lined up to collaborate with Hadid: Chanel, Adidas (with Pharrell Williams), jewelers Swarovski and Georg Jensen, Moleskine, the German yacht makers Blohm+Voss, and of course that $2,000 sculptural “haute couture” shoe. Long before today’s ”Lean In” movement, Hadid was a single, stylish, workaholic woman who ran a 400-person firm, and refused to shrink from controversy.

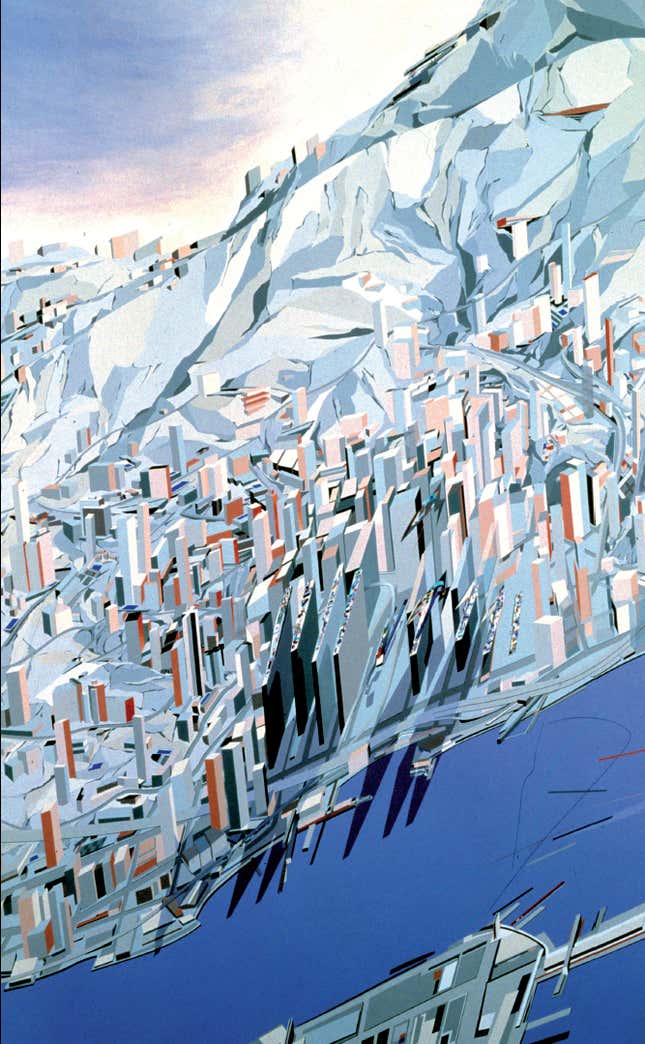

Hadid’s reputation was built on drawing ideas ahead of their time. Her early architectural renderings, drawn in a distinctive style influenced by the Russian abstract art movement Suprematism, were usually technologically impossible to realize.

“Hadid’s work in the 1980s and early 1990s was startling,” explains architecture critic Alexandra Lange to Quartz. “She hadn’t built any of it yet—and it would be some time before she could—but her drawings were like a portal into another world.”

“She had the tenacity to stick to it until technology and public taste caught up to the idea that a building could look like it was always in motion,” says Lange.

The Pritzker Prize, and a disdainful press

Hadid received her career-defining prize, the 2004 Pritzker, at the relatively young age of 53 despite only having a small body of built work. The accompanying headline of the official announcement—”Zaha Hadid Becomes the First Woman to Receive the Pritzker Architecture Prize”—signaled the tenor of the media coverage to follow.

Never mind the groundbreaking museum she designed in Cincinnati or the wonderfully weird fire station in Weil am Rhein, Germany or confounding design concepts, many profiles of the star architect fixated on her womanliness. A 2004 New Yorker profile introduced Hadid’s work by way of her ”remarkably emotive face, which veers from sweetly girlish to volcanically enraged.”

In a new book Where Are the Women Architects?, historian and architecture professor Despina Stratigakos argues this gendered portrayal of Hadid’s person, and the kinds of questions she was often asked to answer, would have been unthinkable treatments for any of the previous 25 Pritzker laureates.

Clichés like “ball-breaking harridan” and “vertiginous heels,” dot this 2004 article by The Guardian‘s Stuart Jeffries:

Zaha Hadid offers a moist, limp hand to shake. She’s coming down with flu. This is a disappointment. Where is the vibrant monster I’d been promised from previous interviews? Where’s the ball-breaking harridan barking abuse in Arabic into her mobile as she wafts into her north-London studio in vertiginous heels, before snarling unpleasant things to her staff in terrifyingly idiomatic Anglo-Saxon?

The New York Times’s influential critic Herbert Muschamp seemed to turn up his nose at her rough-and-ready energy. ”She is not someone you would talk to about books,” Muschamp wrote. “Earthier appetites seem to drive her. I myself do not care greatly for lamb testicles. Should a sudden craving for this delicacy come over me, however, I would know whom to call.”

The Financial Times’s reporter Edwin Heathcote dared to ask Hadid if she even really deserved to win the Pritzker, architecture’s highest honor. “I don’t know how to answer that…some people must think I deserve it,” she replied.

Years later, with even more accolades and built projects under her belt, Hadid still refused to justify or qualify her achievements. At Oxford University just last month, a student similarly puzzled the architect by asking how she thought future architecture historians would appraise her work.

“I really don’t know,” she said, after patiently listening to the long-winded question. She was just doing her thing, she would often say.

A role model, but never a mold

While there are many talented, recognized and respected female architects practicing around the world, Hadid was the only one to have so clearly punched a hole in that proverbial glass ceiling. For many rising female architects, losing Hadid is like seeing a beacon in the field extinguished.

“Her loss is devastating,” says Stratigakos, who also heads the architecture department at the University at Buffalo. “You lose heart when you can’t find role models. I worry about how few women architects there are–not just in Pritzker prizes, but in novels, in films… I worry about my students.”

According to a 2014 study by the San Francisco chapter of the American Institute of Architects, one-third of women drop out of the profession citing the lack of role models as a reason. Over 70% of women experience sexual discrimination, harassment or bullying on the job.

But Hadid was a complicated figure, and not exactly the easiest role model. She was notorious for refusing to back down from criticism over her selection of clients or the working conditions of the people who built her designs. And her professional success was tightly intertwined with her force of personality and uniquely groundbreaking ideas—a formula few could hope to replicate.

As Hadid explained to the students in Oxford, she put ideas first—and often before practicality or the wishes of her clients. “I believe in progress, I think if we do enough research, we can push the envelope and get better results… That’s what I like about architecture. It’s exhilarating, but also heart-breaking.”

Two heartaches were the Cardiff Bay Opera House in Wales in 1994 and the ongoing saga of the Tokyo Olympics stadium in Japan. Both were politicized, high-profile commissions that seemed entranced by Hadid’s ideas, then abruptly spurned her for another architect.

Proudly Arab and Iraqi

Hadid was also widely-revered in the Arab world, as one of few Arab women to have gained international celebrity status. “I first read about Zaha in the seventh grade,” says Loubna Mrie, a Syrian colleague at Quartz. “We always used her as an example. Yes, smart, successful women exist. Look at Zaha, we would say.”

Born to an affluent family of Sunni Muslim Arabs in Baghdad, Hadid was educated in Catholic school, and studied mathematics at the American University in Beirut, Lebanon. She later studied at London’s Architectural Association School of Architecture (AA), became a teacher, and established her practice there in 1980. She died a naturalized citizen of the UK.

From the very beginning of her career, Hadid stood out. Of her time at the Architectural Association School, former classmate and architect Deborah Berke says: “She was a genius even then. Her talent was unmistakable.”

Hadid never forgot or dismissed her roots. In a revelatory 2014 interview with Lebanese journalist Ricardo Karam, Hadid said she disliked that journalists often confused her nationality and her citizenship.

“It’s always bothered me…I’m an Arab and an Iraqi,” Hadid said. “I’m not Brit-English, I’m not half English, I just live here [London].”

An outsider in so many ways, Hadid burst into the greatest heights of architecture and stayed there, a vital proof to others that a woman—and an Arab woman—could do it. When, at the end of her lecture at Oxford, a young man asked for career advice, Hadid offered the only advice she could. ”There is no real magic,” she said.

“It’s really hard work.”