On Aug. 3, 378, a battle was fought in Adrianople, in what was then Thrace and is now the province of Edirne, in Turkey. It was a battle that Saint Ambrose referred to as “the end of all humanity, the end of the world.”

The Eastern Roman emperor Flavius Julius Valens Augustus—simply known as Valens, and nicknamed Ultimus Romanorum (the last true Roman)—led his troops against the Goths, a Germanic people that Romans considered “barbarians,” commanded by Fritigern. Valens, who had not waited for the military help of his nephew, Western Roman emperor Gratian, got into the battle with 40,000 soldiers. Fritigern could count on 100,000.

It was a massacre: 30,000 Roman soldiers died and the empire was defeated. It was the first of many to come, and it’s considered as the beginning of the end of the Western Roman Empire in 476. At the time of the battle, Rome ruled a territory of nearly 600 million hectares (2.3 million square miles, nearly two-thirds the area of the present-day US), with a population of over 55 million.

The defeat of Adrianople didn’t happen because of Valens’s stubborn thirst for power or because he grossly underestimated his adversary’s belligerence. What was arguably the most important defeat in the history of the Roman empire had roots in something else: a refugee crisis.

Two years earlier the Goths had descended toward Roman territory looking for shelter. The mismanagement of Goth refugees started a chain of events that led to the collapse of one of the biggest political and military powers humankind has ever known.

It’s a story shockingly similar to what’s happening in Europe right now—and it should serve as a cautionary tale.

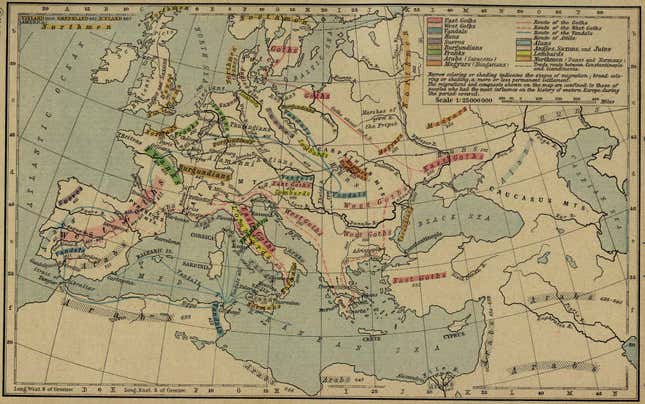

According to historian Ammianus Marcellinus, in 376, the Goths were forced to leave their territories, in what’s now Eastern Europe, pushed south by the Huns, in Marcellinus’s words, “a race savage beyond all parallel.” The Huns, Marcellinus writes, “descended like a whirlwind from the lofty mountains, as if they had risen from some secret recess of the earth, and were ravaging and destroying everything which came in their way.”

It resulted in terrifying bloodshed, and many of the Goths—like many Syrians and others displaced by war—decided to flee.

They decided that settling in Thrace, right across the Danube river, was the best solution; the land was fertile, and the river would provide defense to keep the Huns at bay.

That wasn’t free land—it was in the Roman empire, under the rule of Valens—and so Fritigern, who was leading the Goths, asked to “be received by him as his subjects, promising to live quietly, and to furnish a body of auxiliary troops if any necessity for such a force should arise.” Rome had a lot to gain from this. Those lands needed cultivating, and more soldiers were always welcomed by the empire. “By combining the strength of his own people with these foreign forces,” Marcellinus writes of Valens, “he would have an army absolutely invincible.”

As a sign of gratitude to Valens, Fritigern converted to Christianity.

It all started rather peacefully. The Romans put in place a service not that different from a modern search-and-rescue program. “Not one was left behind,” Marcellinus writes, “not even of those who were stricken with mortal disease.” The Goths “crossed the stream day and night, without ceasing, embarking in troops on board ships and rafts, and canoes made of the hollow trunks of trees.” Marcellinus recounts that “a great many were drowned, who, because they were too numerous for the vessels, tried to swim across, and in spite of all their exertions were swept away by the stream.”

It was an unexpected, unprecedented flow (some estimates say up to 200,000 people). Officials in charge of managing the Goths tried to “to calculate their numbers,” but determined it was hopeless.

Traditionally, the Roman attitude toward “barbarians,” though autocratic, had been pretty longsighted. Populations were often sent where the empire needed them the most, with little regard to where they wished to stay; however, there was a strong push toward assimilation that eventually turned foreigners into citizens. Descendants of immigrants would routinely be seen in the high ranks of the military or the administration. The recipe that kept the empire safe from attack from other populations was simple: allow them into the empire and make them Roman.

But things eventually changed. The military officials who were in charge of provisions for the Goths—an ancient version of the support offered to migrants arriving in Greece or Italy—were corrupt and profited off of what was meant for the refugees. The starving Goths were forced to buy dog meat from the Romans.

Marcellinus has no doubt: “their treacherous covetousness was the cause of all our [the Romans’] disasters.”

The trust between the abused Goths and the Romans was broken several times before Adrianople, and the Goths went from wanting to become Roman to wanting to destroy Rome.

Less than two years later, Marcellinus writes, “with rage flashing in their eyes, the barbarians pursued our men.” And they took down the empire.

The migrants trying to get to Europe right now are not about to rise up in arms, and Europe is not—thankfully—the Roman empire. But this story shows well that migration has always and will always be a part of our world. There are two ways to deal with refugees: one is to promote dialogue, and inclusion; the other is to be unwelcoming and uncaring. The second has led to disaster before—and in one way or another, is sure to do so again.