There were hundreds of children on the platform that cold morning, some gripped with fear, others utterly confused. What was England? And why were they being sent there? It was only three weeks ago that a savage mob swept through their neighborhoods like wildfire, leaving behind a trail of broken lives.

The parents didn’t dare to say goodbye—the word brought an uncomfortable sense of finality. They whispered desperate promises instead.

We’ll follow you.

We’ll see you soon.

This is only temporary.

Milling among the chaotic crowd on Dec. 1, 1938, was Leslie Baruch Brent, carrying his packed lunch and a piece of fruit. His mother, father, and older sister were one of many families putting on a brave face as they huddled him onto the train. Others collapsed underneath the weight of their agony; one father handed over his four-year-old child, only to snatch him back at the last minute before the train roared to life.

For Brent, then all of 13 years old, it was an adventure into the unknown. His carriage was packed with strangers, though there were some familiar faces. German police stomped up and down the train as it sped through the German countryside. Panic set in every time the train stopped. Would they be forced to turn back? Then something remarkable happened as soon as they crossed the Dutch border.

“There were all these wonderful Dutch women on the platform smiling at us. We weren’t used to anyone smiling at us,” Brent recalls. “We were outcasts.” The Dutch women handed out chocolates, sandwiches, and drinks.

He then boarded a large ferry to his new home—England. And just like that, he escaped the Nazis.

Brent was in the first batch of 10,000 children who arrived there, thanks to a remarkable British humanitarian program that would come to be known as the Kindertransport. Britain relocated children from Germany, Austria, and Czechoslovakia to the UK from December 1938 to the outbreak of the Second World War nine months later.

“It was an extraordinarily generous thing to have done, which was unparalleled anywhere in the world,” Brent says.

“No oksijan in the car”

For some children, the journey across Europe is far more dangerous today.

Seventy-eight years after Kindertransport, Europe is experiencing the worst refugee crisis since World War II, one largely characterized by the staggering number of children crashing onto Europe’s shores by themselves. More than 1.2 million people sought asylum in the EU last year, and around 30% of them—almost 370,000—were minors. A quarter of those children were unaccompanied.

Many of these children, who are desperate to reach Sweden, Germany, or the United Kingdom, are not only taking tremendous risk to do so, but are also especially vulnerable to sexual exploitation or human trafficking as they embark on their perilous journey. This year alone, the squalid refugee camp in Calais, France known as the Jungle has had to mourn the death of 15-year-old Masud and then 17-year-old Mohammed Hassan, who hid underneath a truck coming into England when it suddenly crashed.

Mohammed was declared dead at the scene, some 14 miles from British prime minister David Cameron’s home.

“We’ve had a number of children killed on the motorway, children killed by trains, electrocuted, suffocated in backs of lorries or fallen off them,” says Liz Clegg, a British volunteer who runs the independent Women’s and Children’s Centre at the Jungle.

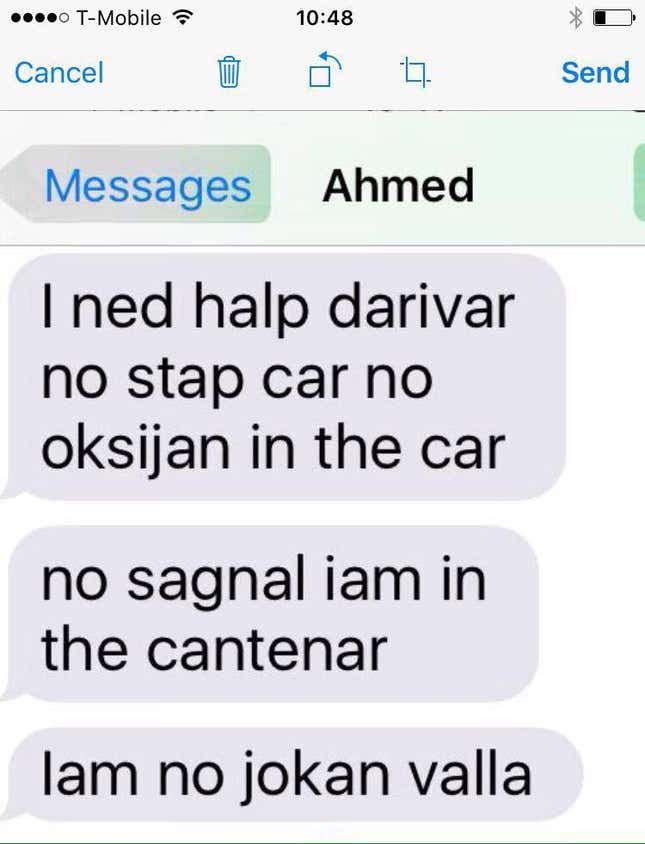

A week after Mohammed’s death, Clegg found herself racing against the clock to save Ahmed, a seven-year-old young refugee boy from Afghanistan, who was trapped in a locked cabin on a truck, quickly losing the ability to breath. Ahmed was able to text Clegg on a phone she had previously given him, telling her he desperately needed help as he couldn’t breathe.

“I ned halp dariver no stap car no oksijan in the car,” he texted.

The text sparked a rapid response from emergency personnel, which saved not only Ahmed’s life, but also the lives of 14 other refugees stowed away in the back of the lorry with him.

“We know of numerous cases of women and children suffocating and having to call for help,” Clegg explains. Ahmed is now safe with British social services, but is still blighted with nightmares. It’s not the Taliban or the smugglers that haunt Ahmed at night.

“He has regular nightmares about the French police chasing him,” Clegg says.

Seeing all this, Rob Lawrie decided to take matters into his own hands. “I don’t consider myself an activist,” Lawrie admits. “I’m not one to chain myself to the railings of Downing Street. But maybe I don’t stick to the law like I should.”

Lawrie made headlines earlier this year for trying to smuggle four-year-old Bahar, an Afghan girl living in the Jungle, into the UK. After seeing the “quagmire of mud” that young children were being forced to live in, Lawrie agreed to take Bahar to her family members in Leeds.

He put her in a sleeping compartment in his lorry. Unbeknownst to him, two Eritrean men had also snuck into the van as he was loading unwanted donations. Within hours, the sniffer dogs had picked up the Eritrean men and while Lawrie was being arrested, he had to admit to the French police that Bahar was also hidden away in the van. “All hell broke loose,” he says ruefully.

He was imprisoned for a week and appeared in court in January in front of the world’s media. A petition to “Free Rob Lawrie“ gained over 100,000 signatures. Lawrie was eventually given a suspended sentence. Bahar was returned to the refugee camp.

Lawrie sighs. “We’re leaving them to rot,” he says.

From Kristallnacht…

The UK originally didn’t want to take in all those children in 1938. Kindertransport was born in circumstances of inertia, too.

By 1938, one Jew in four was fleeing Nazi Germany and thousands of Polish Jews had been expelled. At a conference in Evian, in southern France, to address the growing refugee crisis, delegates expressed sympathy—but none offered practical help. The US enforced immigrant quotas to keep them out. Lord Winterton, Great Britain’s representative, went so far as to declare: “The United Kingdom is not a country of immigration.”

It wasn’t until Kristallnacht, the “night of broken glass“ in November 1938, in which a wave of anti-Jewish pogroms spread through Germany, that the British government reconsidered its position. More than 200 synagogues were destroyed and 30,000 men were rounded up simply for being Jewish, soon to be sent to concentration camps.

Buckling under pressure from Jewish and non-Jewish charity groups, prime minister Neville Chamberlain agreed to take in an unspecified number Jewish children under the age of 17—on the condition that £50 was paid for each child.

Jews, Quakers, and Christian volunteer organizations were the engine that kickstarted the Kindertransport and kept it running; they pressured the government to take in child refugees on temporary travel visas, worked against the clock to find the most vulnerable children to be relocated, and scouted for potential English couples to take in these children. “My mum’s first primary job was to save her children,” says Karl Grossfield, who was 12 when he boarded the train from Vienna.

Grossfield and Brent are close friends, bonded by their shared trip almost 80 years ago. Recently, Brent hosted a small gathering with close friends who’d also been saved by the Kindertransport, which included Grossfield and acclaimed British painter Frank Auerbach. Though they were brought together by tragedy, Grossfield remembers the shared consensus was that without it, “they would not have had such an interesting life.”

…to now

Cameron rejects the comparisons of today’s refugee crisis with Kindertransport, noting that taking refugees from its neighbors now is very different to taking them from Nazi Germany. “To say that the Kindertransport is taking today children from France or Germany or Italy, safe countries that are democracies, I think that is an insult to those countries,” the prime minister said.

In the present day, 70,000 British people have signed a petition calling on the government, which had already agreed to resettle 3,000 vulnerable child refugees based in the Middle East, to also give this sanctuary to unaccompanied child refugees already in Europe. Tellingly, a recent poll suggested the UK was among the most welcoming nations to refugees in the world.

Many of those calling on the government to provide sanctuary for child refugees are themselves Jewish refugees who were saved by the Kindertransport. The chairman of Kindertransport-Association of Jewish Refugees, Sir Erich Reich, wrote in an open letter that the government do more to “help some of the most vulnerable victims” of the Syrian war.

The UK government has refused to resettle refugees who had made their way to Europe to discourage people from paying traffickers and risking their lives. Instead, the UK’s response to the refugee crisis has been to pump money into refugee camps bordering Syria, recently increasing funding to more than £2.3 billion ($3.3 billion).

This was slammed by critics as hundreds of thousands of refugees, many of them children, were languishing in Europe. They have tried to force the government’s hand. In April, Lord Alfred Dubs, himself a child passenger on the Kindertransport, added an amendment to a recent bill that introduced a series of reforms to crack down on illegal immigration The so-called Dubs Amendment asked the government to also take in 3,000 unaccompanied minors into the UK.

The government at first refused. Cameron insisted that by granting asylum to refugees who’ve already traveled to Europe, he’d “be encouraging people to make this dangerous journey.” The amendment was defeated by 294 votes to 276. The vote was followed by a massive outcry. ”For the first time in my life, I was ashamed of my adopted country,” says Dame Stephanie Shirley, who was five when she boarded the Kindertransport.

Earlier this month, Cameron finally announced the British would be taking in an unspecified number of lone child refugees in Europe. The announcement came with one important condition—children eligible for resettlement would need to have registered in Greece, Italy, or France before March 20, 2016.

For now, it’s unclear how a list of the most vulnerable children will be drawn up, or whether the government plans to relocate tens, hundreds, or thousands of child refugees. “The most vulnerable children aren’t going to be registered,” Clegg says. The Home Office and Downing Street are remaining tight-lipped on the details.

Jonny Willis, a volunteer who runs the Refugee Youth Service that supports 12 to 18-year-old boys living in the refugee camps in Calais and Dunkirk, agrees. In Calais, refugees can sleep in container accommodation, so long that they register their fingerprint. But Willis says many children have refused. “If they won’t register their fingerprint here to stay in warm accommodation, then they’re not going to have registered their fingerprint in Greece,” he says.

Last year, the EU calculated that Britain’s fair share of the unaccompanied child refugees in Europe was 11.5% of what was then thought to be 26,000 unaccompanied children refugees, which would have been 3,000. But with the number of unaccompanied children now closer to 90,000, Britain’s fair share is somewhere around 10,000 children. Britain took in that many child refugees within nine months in 1938.

More than 10,000 child refugees have already disappeared after arriving in Europe, according to Europol, the European law enforcement agency.

One last goodbye

The plight of the children stranded in Europe has bothered Brent deeply. “Painful, dreadful, and shaming” are a few of the words he used. ”I find absolutely distressing and shocking the government present attitudes to refugees in general,” he says.

“The trouble is we never learn from history,” he continues. “Humankind never learns from history. We make the same mistake over and over again.”

Now aged 90, Brent wears his new identity like a second skin. He has an English accent, wife, and an English name.

He was actually born Lothar Baruch, in Köslin, northeast Germany (now Koszalin, Poland). He successfully made the transition from refugee, to an officer in the British army, to a well-respected professor of immunology. He had quite mixed feelings about Germany for a while; he didn’t speak the language for many years and didn’t teach it to his children.

But eventually he decided to return to his hometown, in 1989. “I felt quite awful in a way being in this town, which I partly recognized and partly didn’t.”

The huge synagogue he remembered so clearly was gone, burnt down during Kristallnacht. The town had grown enormously and was largely rebuilt because the Russians had destroyed much of it. Brent didn’t know anyone there; it was now entirely Polish. “It was quite difficult for me,” he admits.

It took him 60 years to find out what happened to his family.

Every meticulous detail of their journey—the date of their deportation (Oct. 26, 1942), the number of people crammed on the train (897), and the length of the journey (three days)—was passed on to Brent a few years ago by the Berlin Archives Office. He was even given his sister’s copy of the lengthy questionnaire that his family was forced to fill out before the deportation. His sister had no valuables to declare, just the clothes she was wearing.

Brent’s family wasn’t gassed in a concentration camp. They were rounded up like cattle, put on a train that stopped in Riga, Latvia, where they were hurried into the woods and shot. He has a few photos left of his family—their passport photos and a picture of his mum as a young woman. He looks at them on a daily basis, and this is how he wants to remember them; smiling, charming, and beautiful. He remembers that his father had once called him ein Sonntagskind—”Sunday’s child,” one of good fortune.

Brent will be making his final trip to Koszalin next month to say his goodbyes. He sometimes wonders what his life would have been like if Hitler hadn’t risen to power, but tries to not dwell on the question.