Fearing for the life of her unborn child, Faatma had begged her husband, Mohamed, to flee the civil war unraveling their country. After traveling overland for a month they crammed themselves on to a boat with 40 other people and set sail. The coast was tantalizingly close when the boat capsized. Mohamed wrapped his arm around Faatma’s waist as they tried to wade ashore. “Shouldn’t it be easier for you to float with your bump?” he asked.

They eventually arrived at a transitional refugee camp. When the UN began busing refugees to more permanent camps, the couple managed to sneak out, and met up with Faatma’s brother in a nearby squat.

There my parents became stateless refugees.

Last month, more than 20 years after my family’s odyssey from Somalia to Kenya—and ultimately to asylum in the UK, where I have lived most of my life—I found myself sitting in a car a mile away from just the kind of place my mother had tried so hard to avoid.

The settlement on the outskirts of Calais, on the northern French coast, has no official name, but everyone calls it “the Jungle.” The estimated 6,000 migrants who live there cohabit with rats and mice, in makeshift shelters frequently exposed to flooding. They have to share 40 toilets with no hand-washing facilities, drink from water sources contaminated by feces, and deal with regular outbreaks of tuberculosis and scabies. (This week a French judge ordered the local municipality to install more toilets and water taps, as well sort out regular garbage collection and medical evacuation routes.)

Yet beyond a small health clinic run by Médecins du Monde, there aren’t many NGOs in the camp. There’s no Red Cross, Save the Children or UN High Commissioner for Refugees. That’s because, says Céline Schmitt, a UNHCR spokeswoman, “Calais is not a refugee camp, it’s a spontaneous settlement.” If the French government declared it a refugee camp, it would have to provide the migrants with decent accommodation, food, and help integrate them into society. It has not.

That means local charities have been forced to fill the void. I was there with one of these groups, London2Calais, as they delivered aid to the Jungle. It was to be both a sad and a surreal visit.

The birth of the Jungle

Migrants first started coming to this spot in Calais in 1992, soon after the outbreak of war in Yugoslavia—right around the time my own parents were fleeing Somalia. The French government opened the controversial Sangatte refugee camp in 1999 to accommodate them, but closed it in 2002, fearful it was attracting too many asylum seekers.

Nonetheless, people have continued coming to Calais, building makeshift camps in abandoned buildings or open spaces. In April this year, after heavy pressure from local charities, the French government opened a day center where refugees and migrants can take showers and eat one meal a day. People started moving out of their scattered squats and settled around the day center. The Jungle was born.

In the last few months it’s nearly doubled in size. (The image above shows where new tents with blue plastic tarps have sprouted in just the last month.) The day center, which was supposed to house the women and children, has already reached full capacity; around 600 women and children are forced to live in the Jungle itself, according to the UN. The lucky ones have more stable dwellings made out of wood, but most are in tents or makeshift shelters that would be destroyed by a mild storm.

The London2Calais group I was with was embarking on its third aid run. It was the biggest delivery yet, with 1,500 packages in 22 cars, organized and distributed by 70 volunteers.

Pascal Froehly watched them arrive, his flushed face etched with lines of exhaustion. A volunteer for Secours Catholique, Froehly has been helping migrants in Calais for nearly six years. Just a few months ago he struggled to support the growing needs of the migrants, but he’s now inundated with help. Hundreds of grassroots groups have popped up since the images of a drowned Syrian child, his body washed up on a beach, were published in every major British newspaper.

The trouble is, because of the Jungle’s informal status, it’s not professional help. “No internationally agreed humanitarian standards are being applied there,” says Nick Harvey, a spokesman for the aid organization Médecins du Monde. As there’s been little international coordination, small grassroots groups like London2Calais have been left to try to coordinate between themselves.

The volunteer groups use Secours Catholique’s local warehouse to divide and pack their aid, then load up the cars again and set out into the Jungle to distribute it. The day I was there, the packing of canned food, oil and flour became more chaotic as the morning wore on. The weight of bags started to vary dramatically. Before the group set off, the volunteers were warned to keep their cars locked at all times and follow instructions carefully. We were offered disposable, white nylon gloves to protect ourselves from tuberculosis and scabies. A few of us declined.

“A cage for brown people”

One volunteer described the Jungle as a “cage for brown people” and it’s easy to see why. We drove by a mile-long fence topped with barbed wire as we headed towards the camp. French police officers guarded the entrance to the motorway above it, observing the migrants moving about below.

I peeled away from the group when we arrived and walked deeper in. I encountered an Eritrean migrant roughly the same age as me. Her name was Yohanna. We were both dark-skinned, dressed in all black, our shoes caked with mud. She eyed me suspiciously.

“Where are you from?” she asked.

“I live in London, but I’m Somali,” I answered.

She smiled and agreed to show me around. It’s important to know where people are from, she later said, as the camp is divided by nationality. The Sudanese are the largest group, but there are plenty of Afghani, Eritrean, Ethiopian, and Somali migrants too. In recent weeks, she said, there had been a notable increase in Syrians.

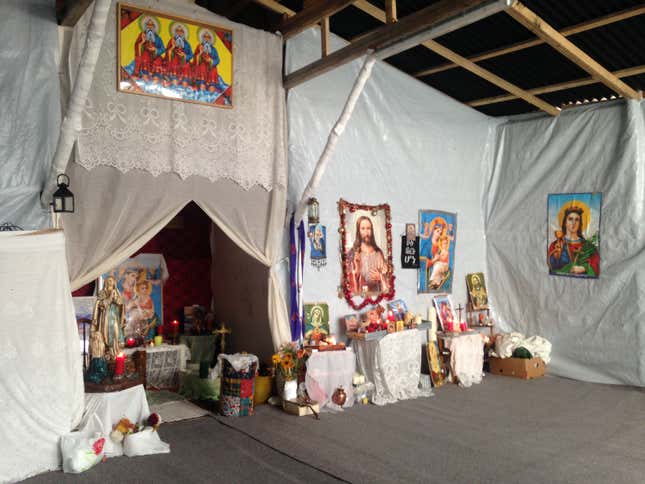

The camp has slowly evolved into a small town. Yohanna pointed out Eritrean bars, Afghani restaurants, and shops offering sweets and cans of Coke. There were several schools and mosques, and a huge church known as St Michael’s.

Inside the church—immaculately clean, by contrast with the rubbish that littered the rest of the camp—I met Samuel, an Eritrean migrant who described himself as one of the church leaders. He had survived a treacherous journey from Libya and was now less than 30 miles (50 km) from his desired destination. “I will never, ever apply for asylum in France. How can I stay in this country? I’m a human being,” he said.

That attitude pervaded the camp. The whole point of reaching Calais, people told me, was to get to Britain. Most migrants either have family there, or already speak English. According to Médecins du Monde, more have been killed trying to cross the English Channel since June 2015 than in the whole of 2014—including being run over by cars, drowning, and being electrocuted while trying to get on a train through the Channel Tunnel—but that doesn’t deter them.

Yohanna shared a tent with two other women in the Eritrean part of town. The four of us crammed in. She asked about life on the other side of the Channel, and I hesitated before deciding to tell them the truth. Prime minister David Cameron has promised Britain will not become a “safe haven” for the “swarm of people coming across the Mediterranean.” Nearly all of the money from the UK has gone to shore up border security; building fences, installing cameras, and deploying police and sniffer dogs.

Yohanna and her friends seemed unfazed. That wasn’t surprising, given what she had been through. She had been kept in a squalid Libyan migrant jail, where she endured near daily beatings, for 18 months. After a Nigerian man helped her escape, she crossed into Europe on a boat, where gun-toting smugglers forced her into the hold (because “the blacks have to go to the bottom,” she said.) For the next five days she was kept in darkness, pressed up against strangers, with nothing to eat or drink, and immersed in the rank smell of feces and urine. If the boat took on water, they would be the first to drown.

Yohanna shrugged and lay on her bed. Other women had worse stories to tell, she said. “The women here are very strong.”

The waiting game

The French police evict migrants who try to set up tents anywhere outside of the Jungle. Local activists report that a nearby Syrian camp was destroyed and the migrants living there were forced to relocate to the main encampment.

When they’re not clashing with police or trying to cross the border and the Channel, it’s boredom that the Jungle’s residents have to battle. Yohanna showed me her favorite place to go as one day rolls into the next—the makeshift library, known as Jungle Books. There were hundreds of books stacked throughout the shelter, and even some donated DVDs, but they sat uselessly on a shelf; there aren’t any TVs in the Jungle.

Another school was being built near the library. Emily, a British volunteer, was there running an informal class teaching English. She’d never done anything like this before, she admitted, but she was keen to help out in whatever way she could.

I headed back to the entrance to reunite with the group I had come with, but I got lost—the camp is that big. I encountered another big aid distribution in progress, and before I got a chance to ask a volunteer if he knew where the London2Calais group was, I was told to get into an orderly line. The man seemed vaguely embarrassed when I told him I wasn’t a resident. He admitted that he didn’t know there was another group distributing aid.

A Somali boy on a bike, named Hussein, helped me find my way. As we walked towards the entrance, I realized how much we had in common. Both our families were from Mogadishu, and both were forced to flee as a result of escalating violence. My British passport started to feel somewhat uncomfortable in my left pocket.

A red car slowed down beside me. The driver poked his head out the window and tried to hand me some bread. He looked puzzled when I politely declined.

When I finally reached my group, they were relieved to see me. A fight had started when they had started distributing aid and people didn’t know if I was safe. Such fights have broken out before, exacerbated by racial tensions. Yohanna complained that some charities only give aid “to the Arabs,” while a volunteer heard a Syrian man telling off the aid group for supposedly only helping black people.

Some of the volunteers started giving out donations to migrants who were milling around. A woman near whom I’d stood while we packed supplies in the morning tried to hand me a bag. Then the realization hit her. “Oh,” she said. “You’re one of us.”

I got a brief moment alone with Yohanna before I left. She hugged me goodbye. Unlike some of the other people I’d spoken to, she didn’t beg me to take her across the Channel. She just said, with a sly smile: “See you in London.”